James Webb Space Telescope

Overview

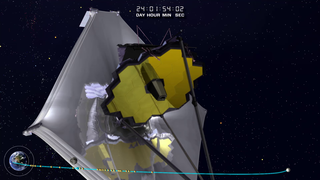

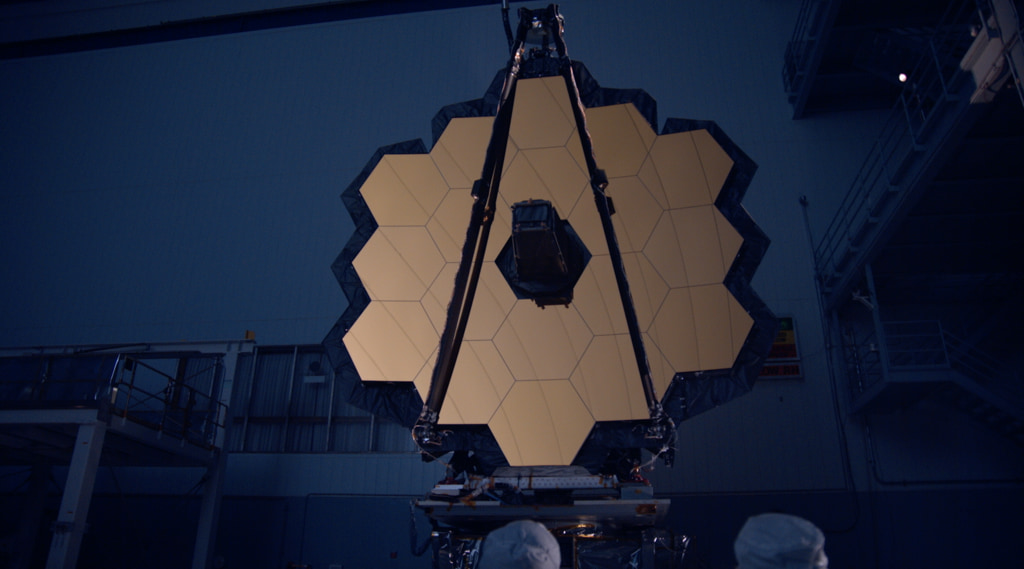

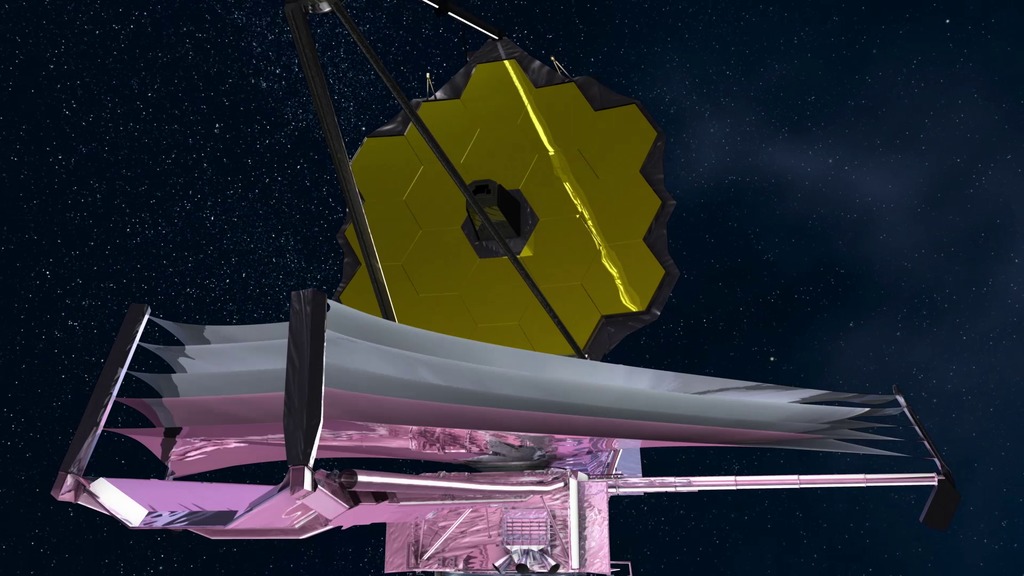

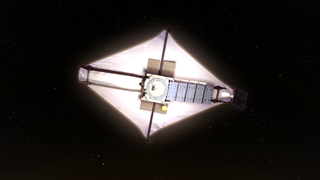

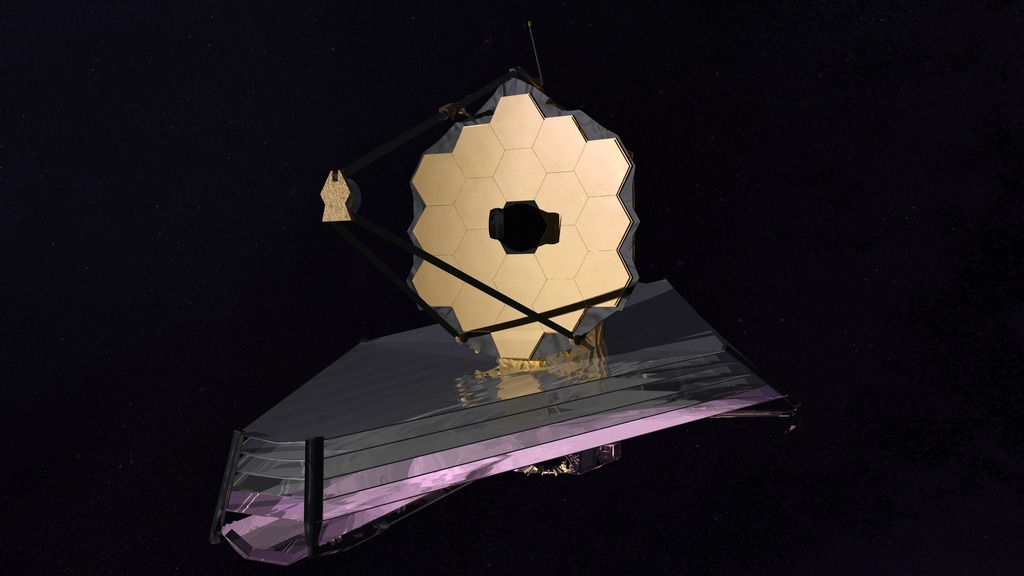

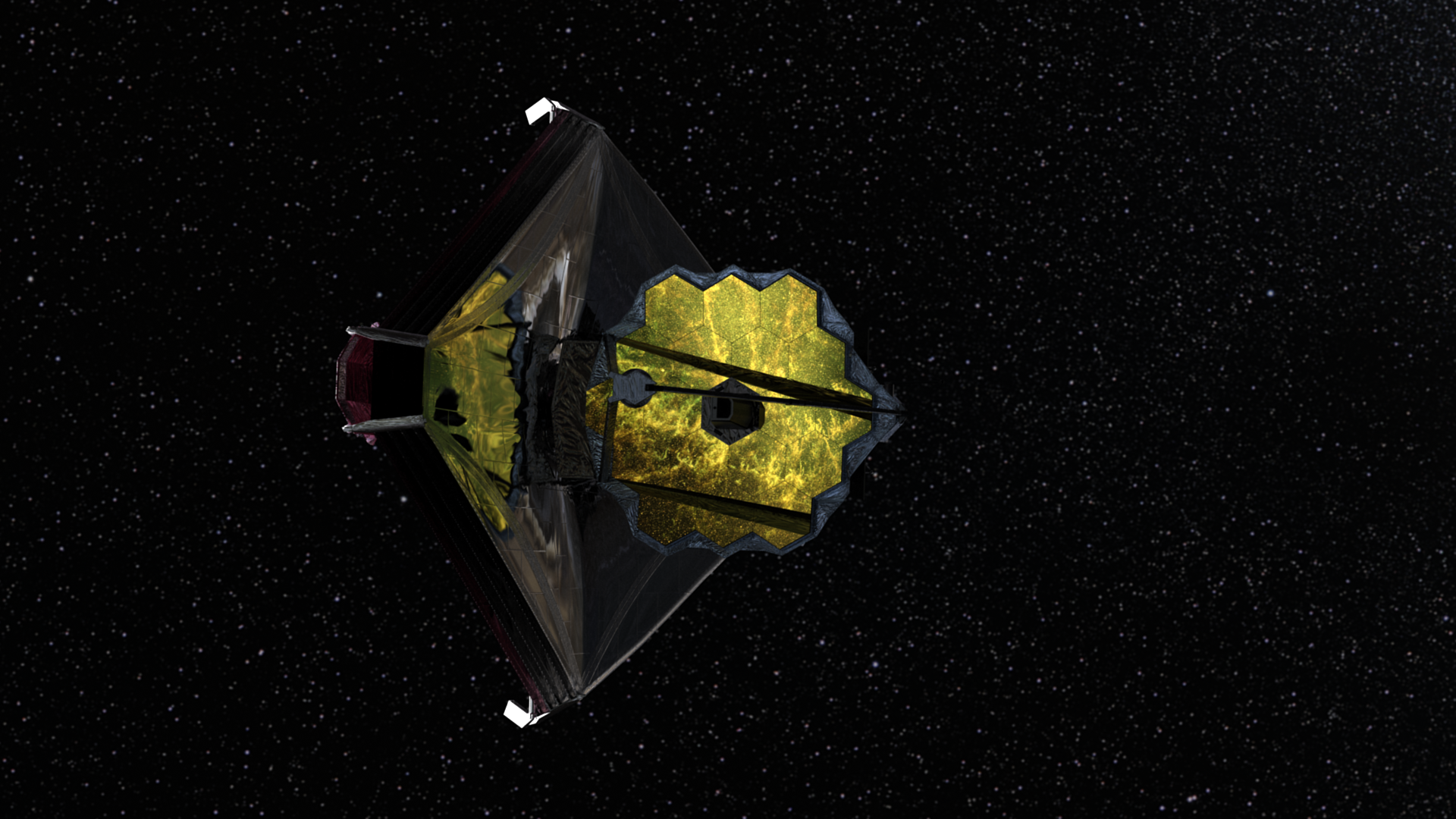

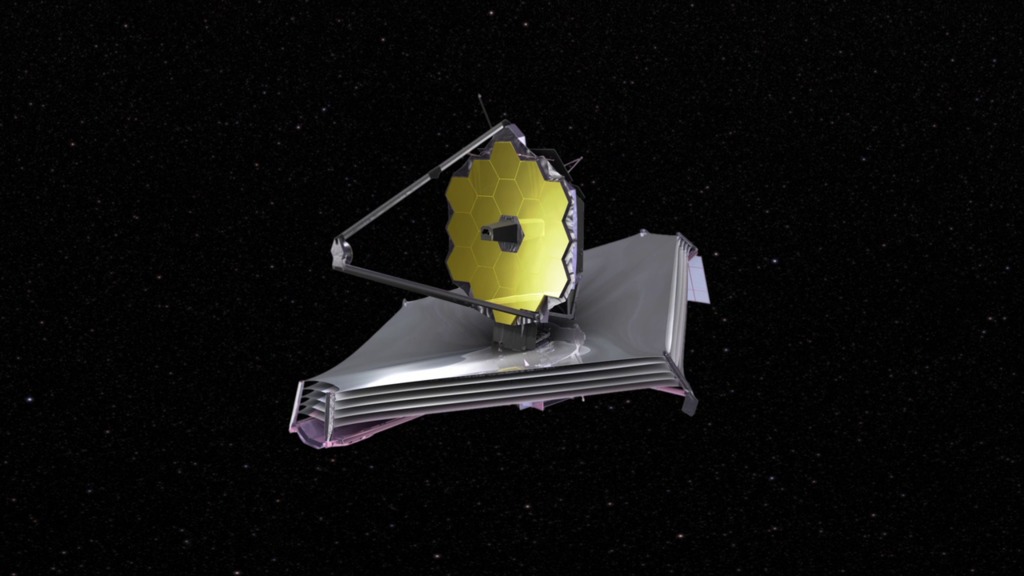

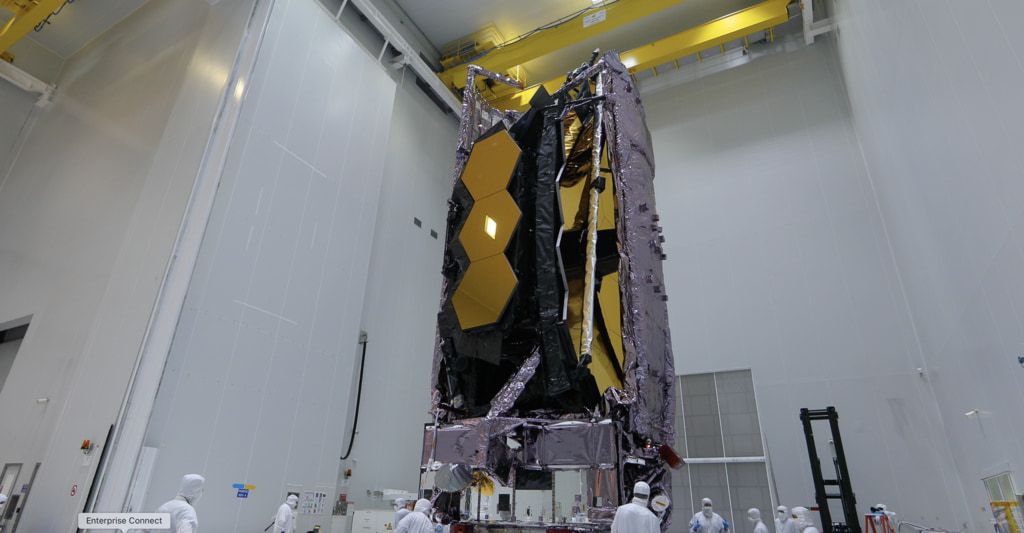

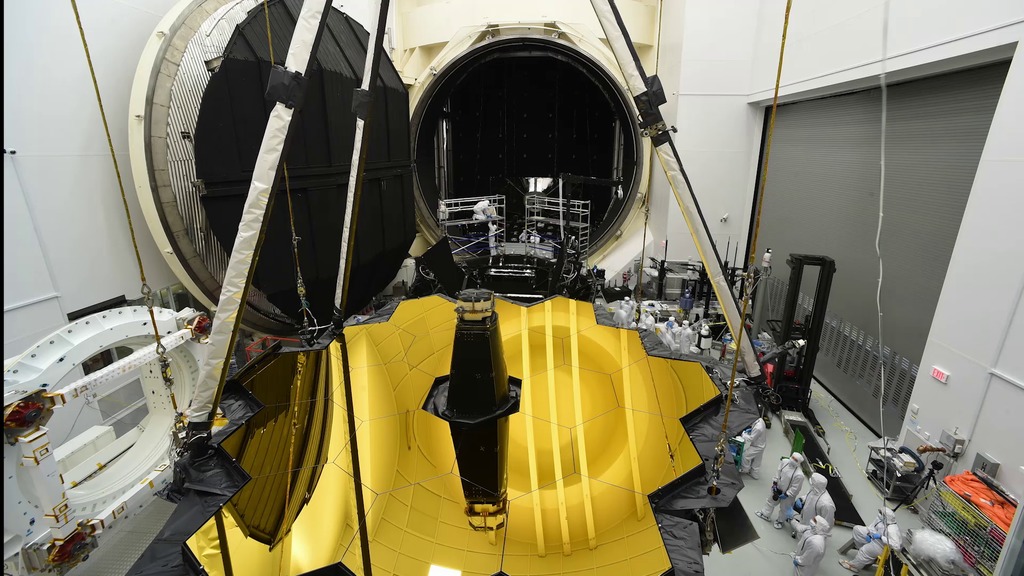

The James Webb Space Telescope (sometimes called JWST) is a large, infrared-optimized space telescope. The observatory launched into space on an Ariane 5 rocket from the Guiana Space Centre in Kourou, French Guiana on December 25, 2021. After launch, the observatory was successfully unfolded and is being readied for science.

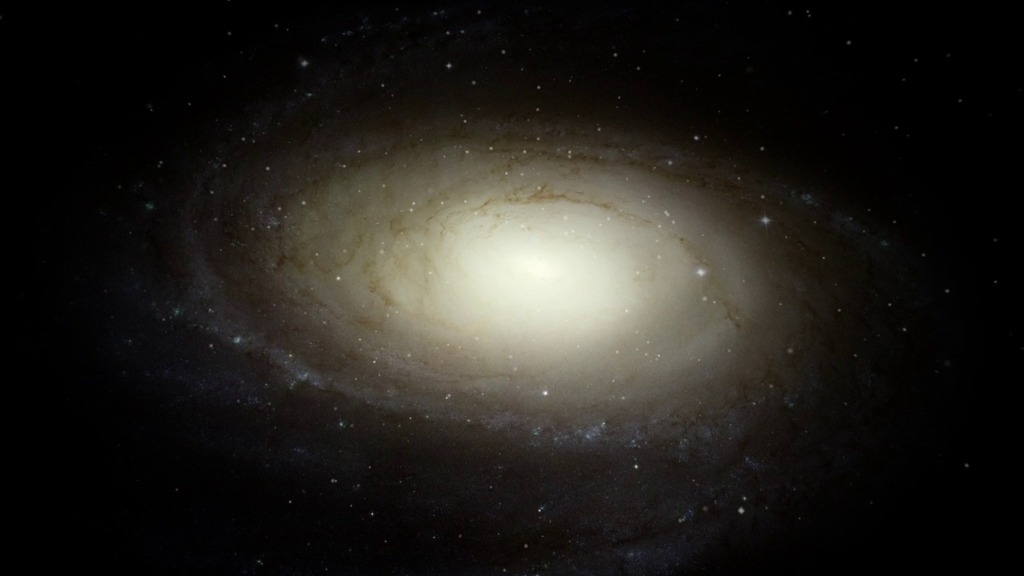

Webb will find the first galaxies that formed in the early Universe, connecting the Big Bang to our own Milky Way Galaxy. Webb will peer through dusty clouds to see stars forming planetary systems, connecting the Milky Way to our own Solar System. Webb's instruments are designed to work primarily in the infrared range of the electromagnetic spectrum, with some capability in the visible range.

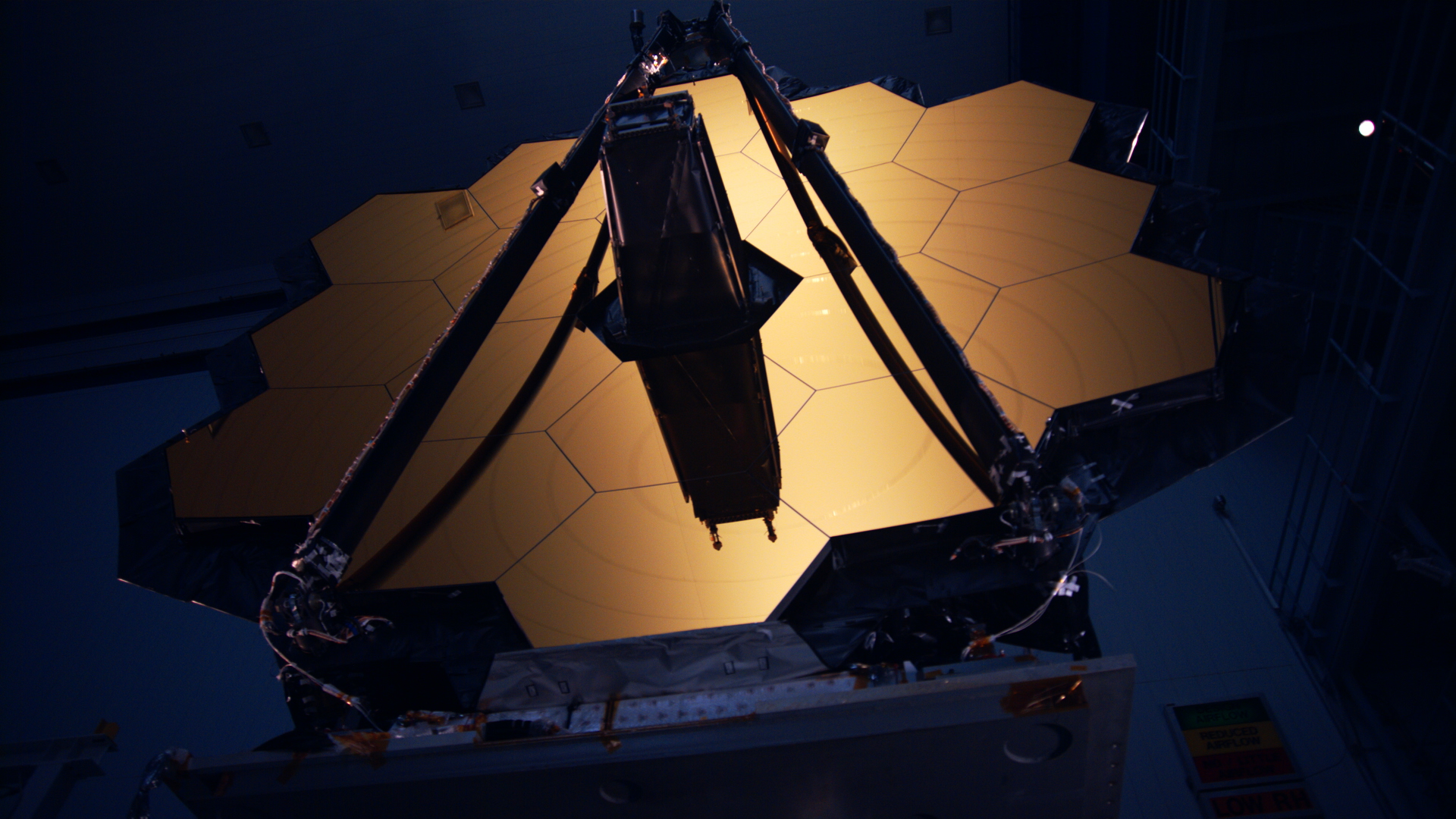

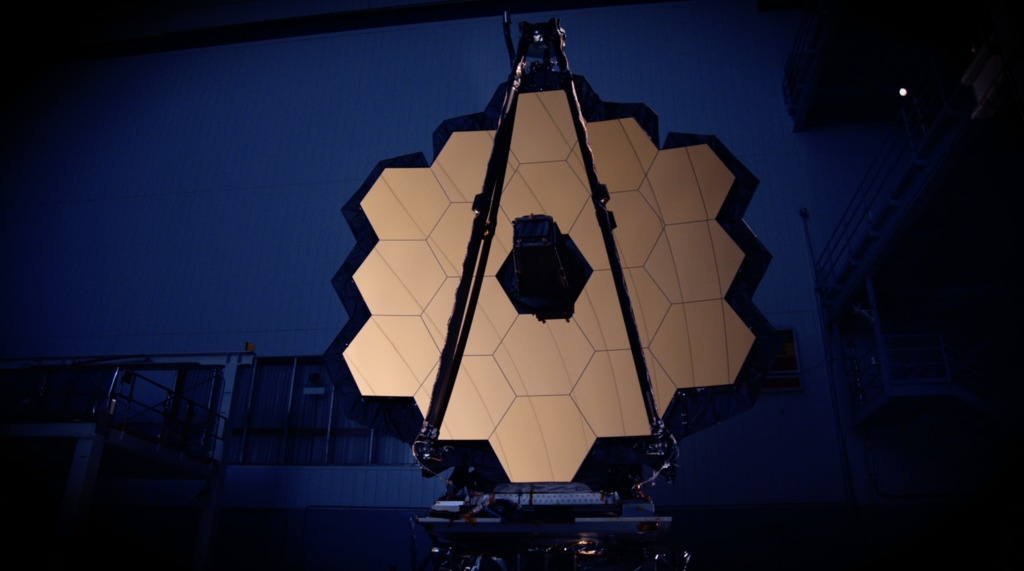

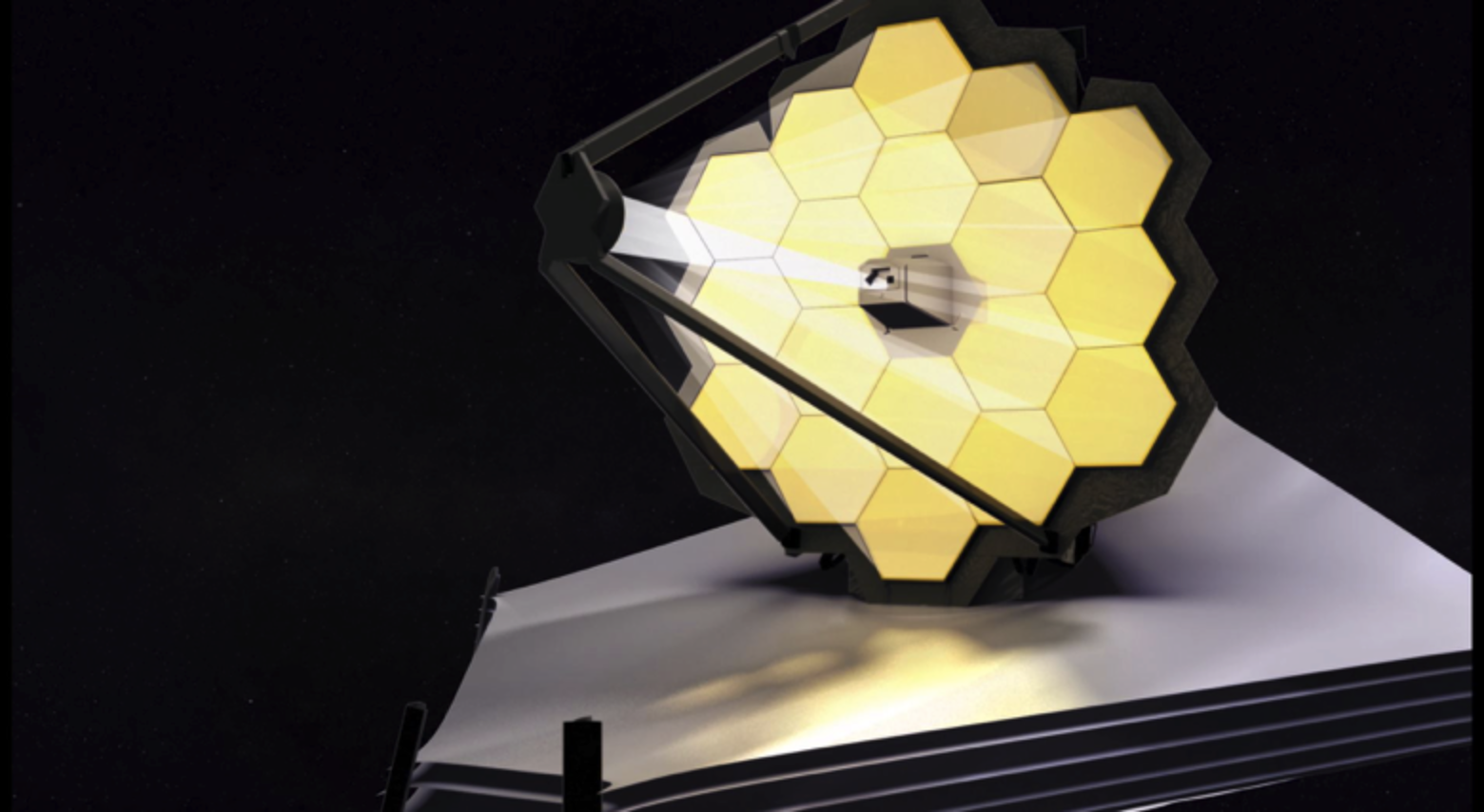

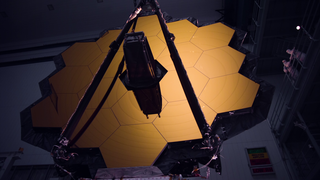

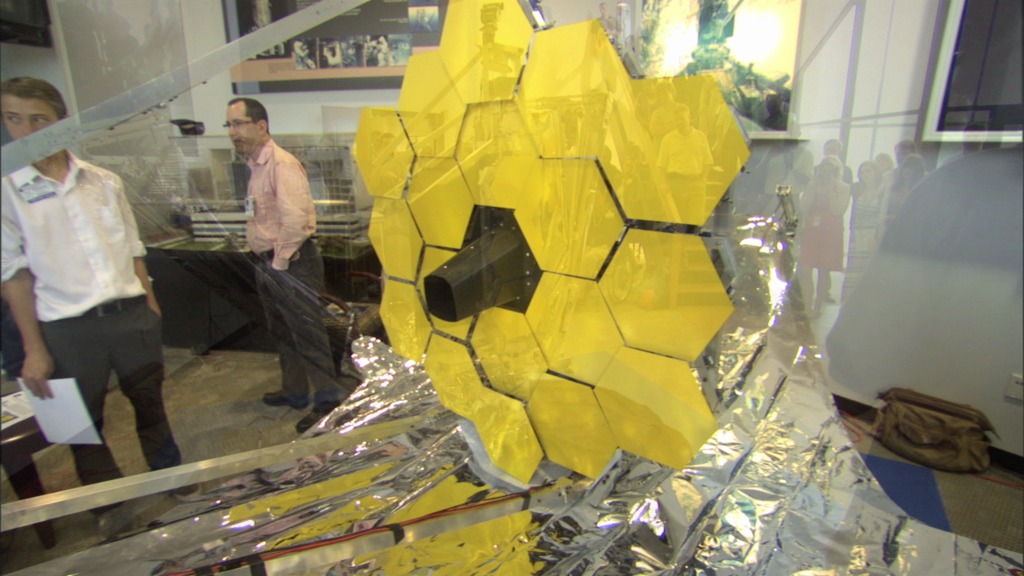

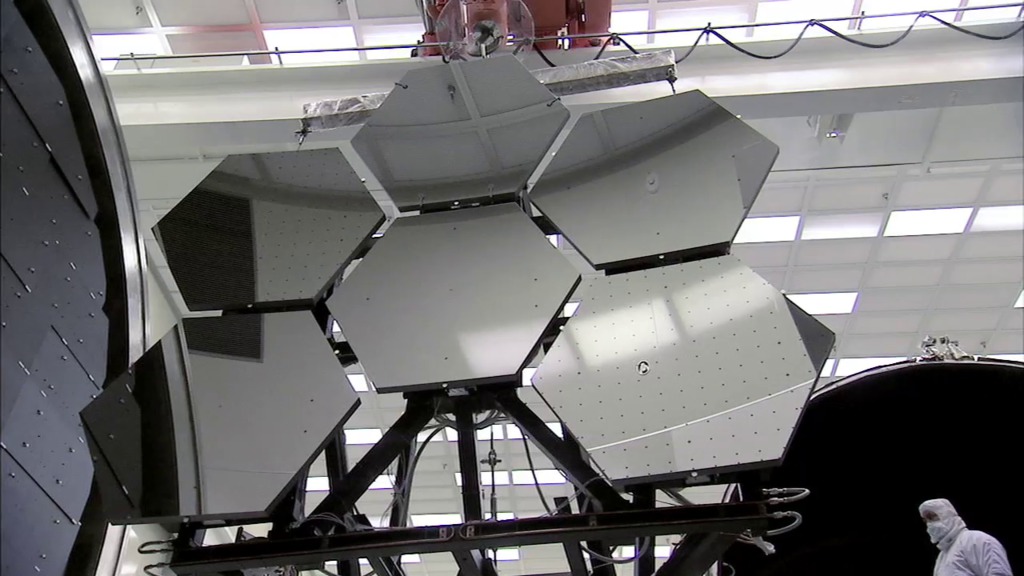

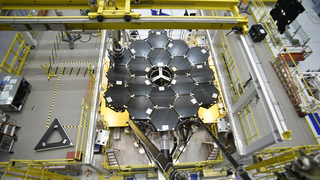

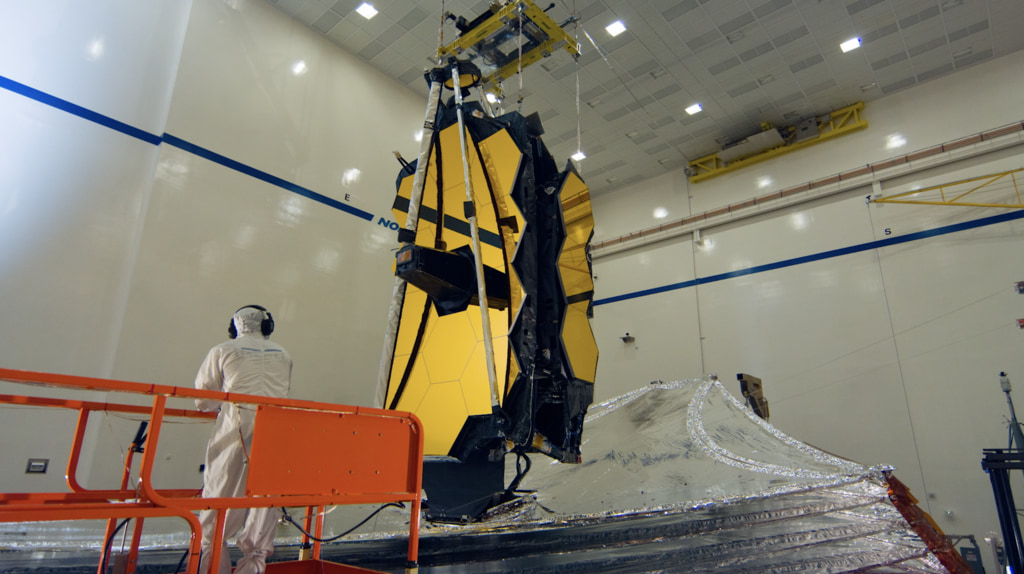

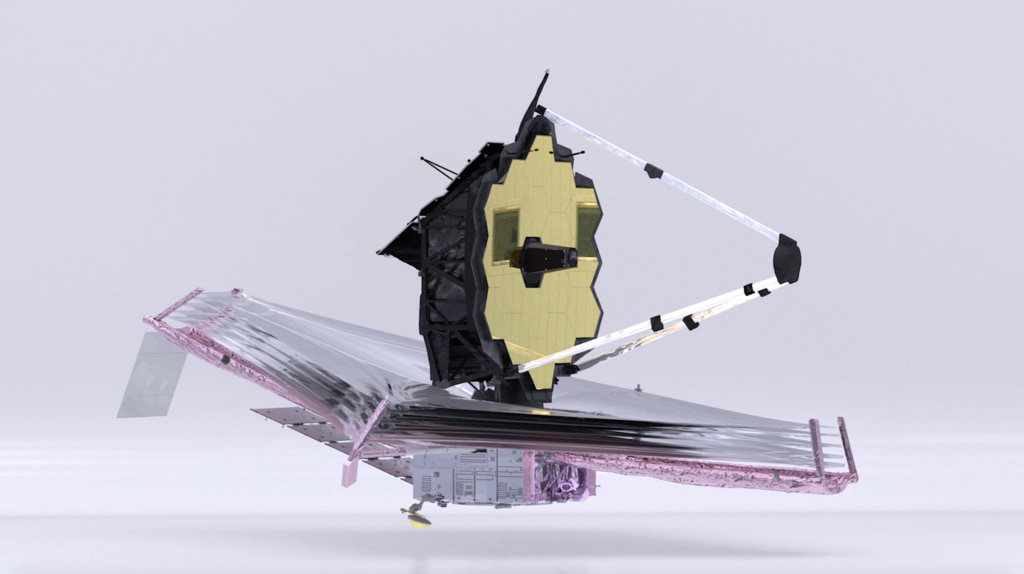

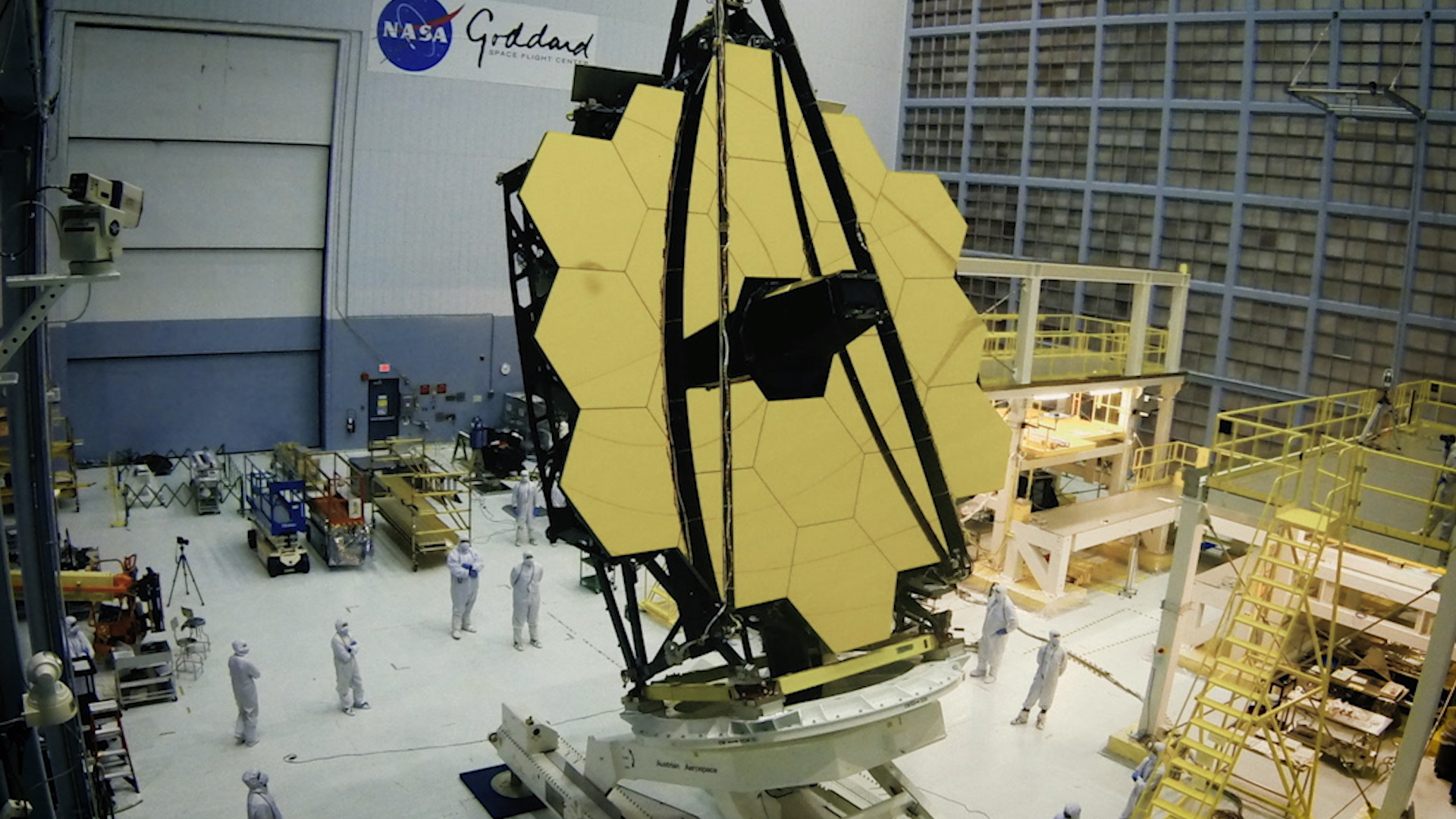

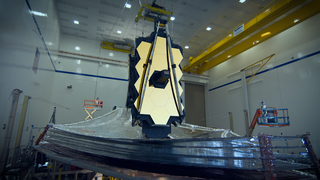

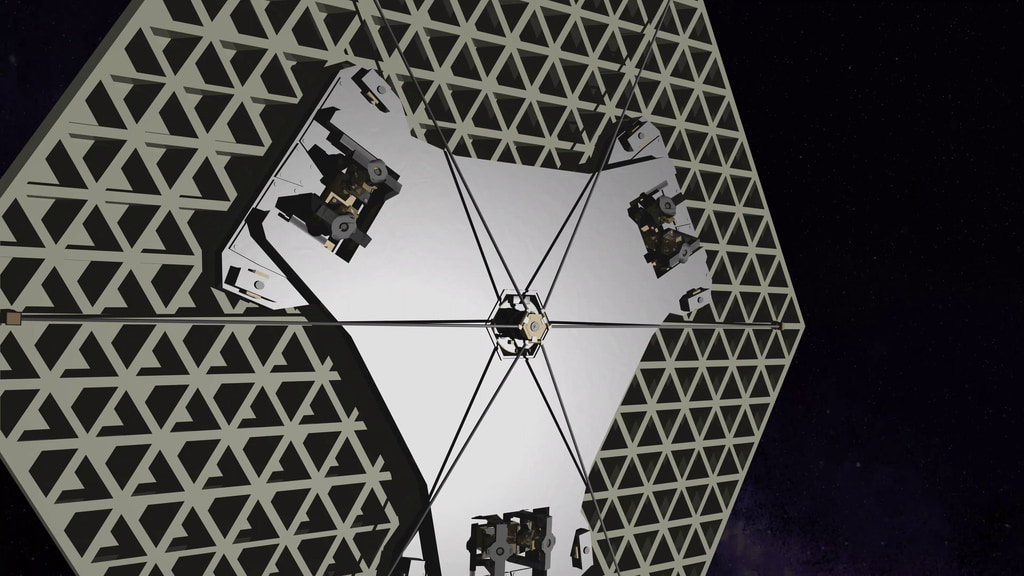

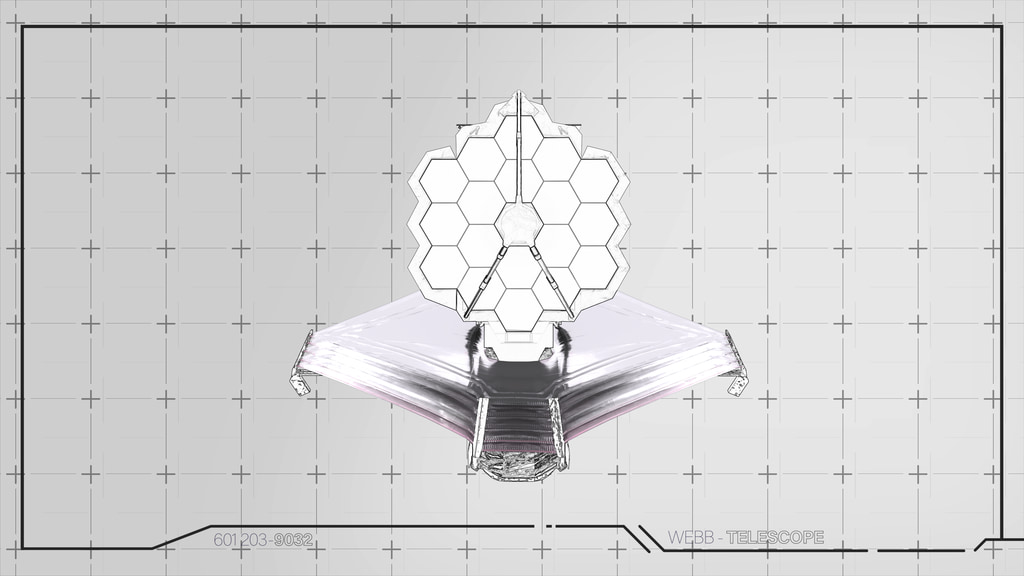

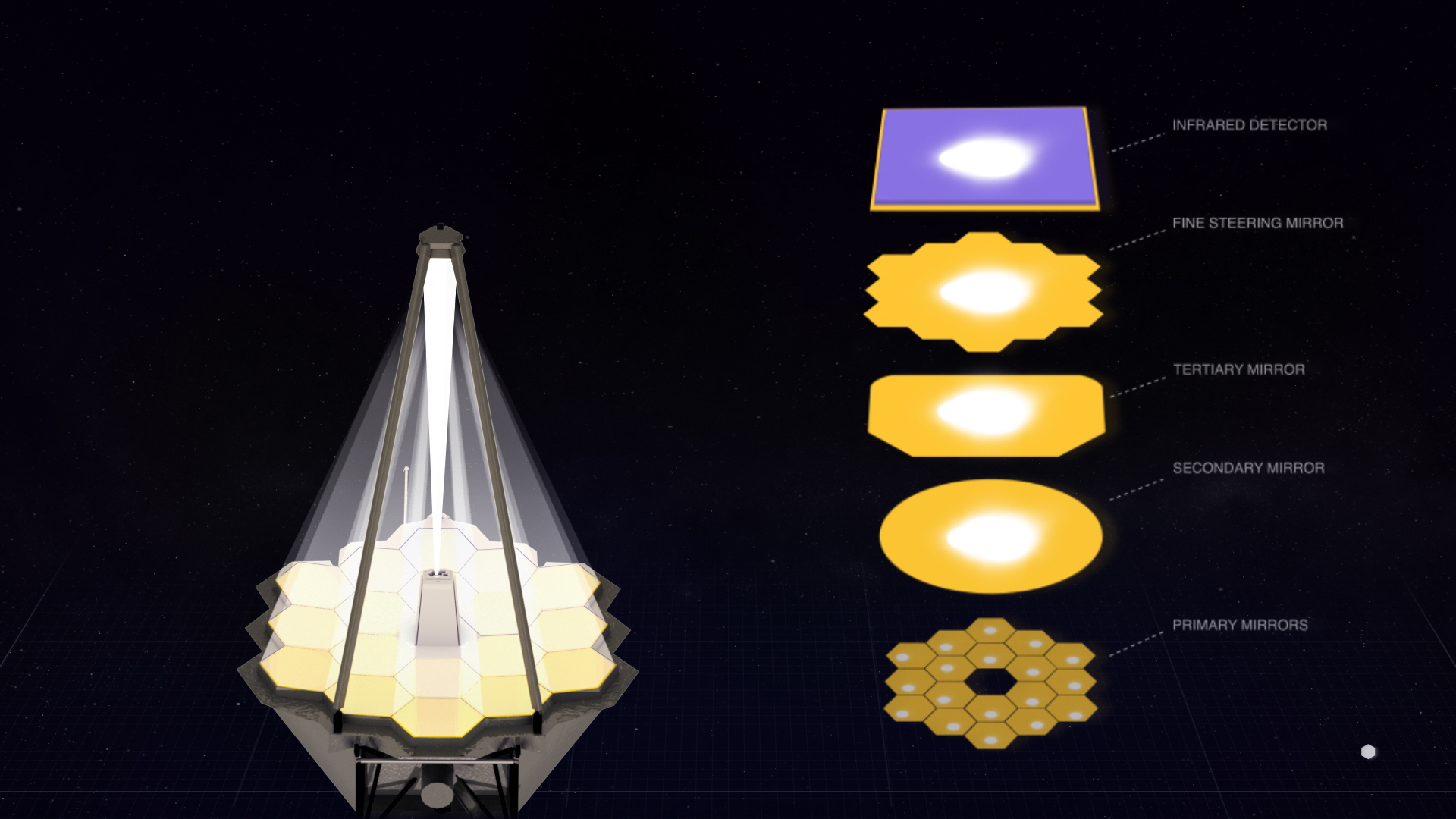

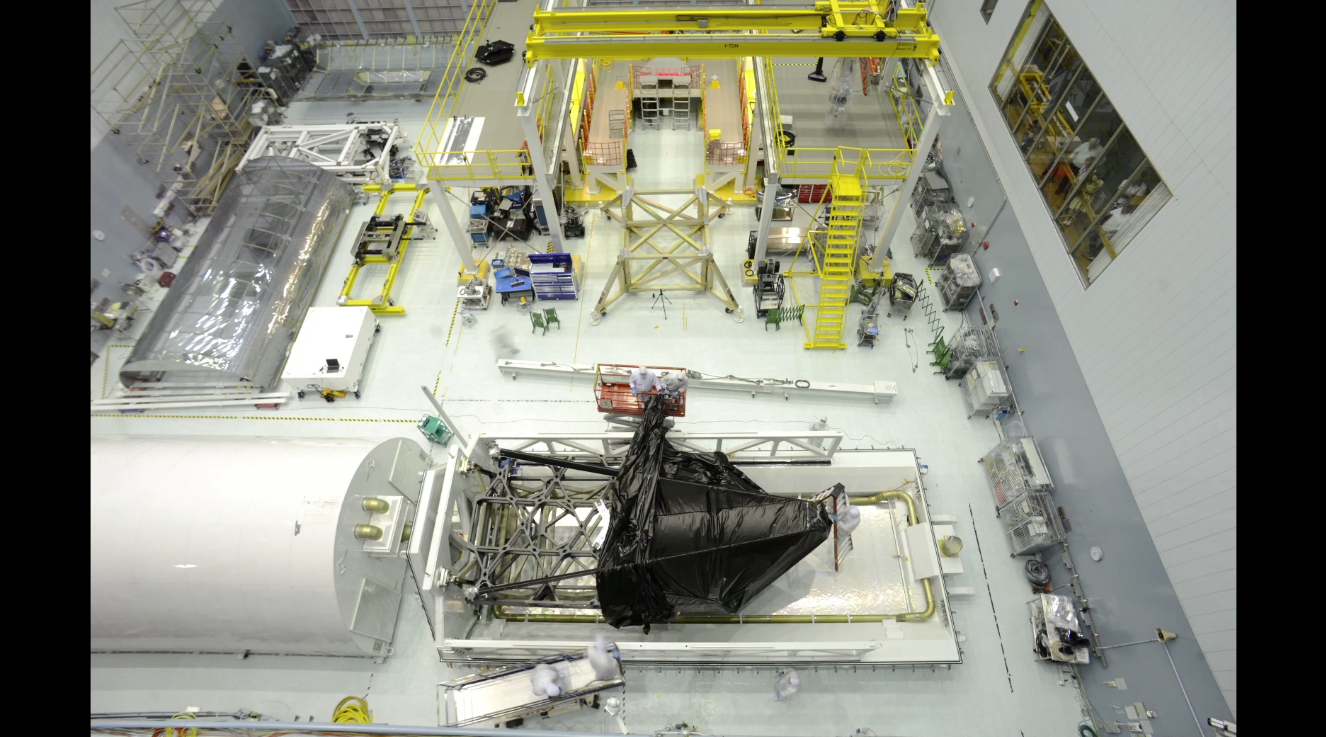

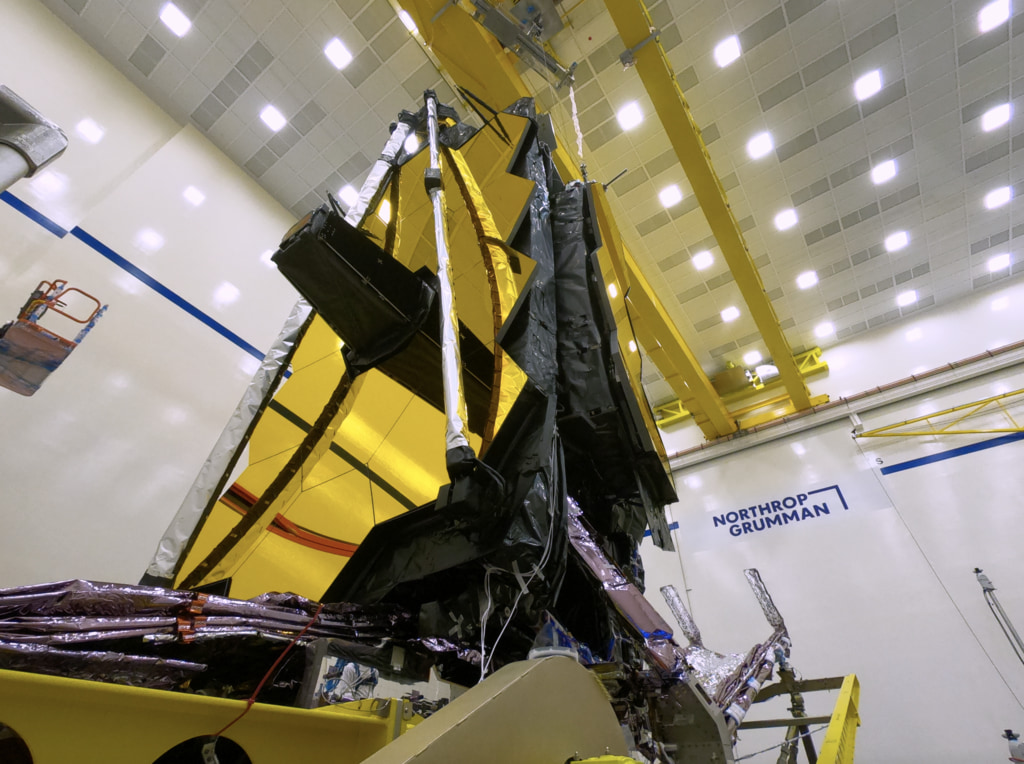

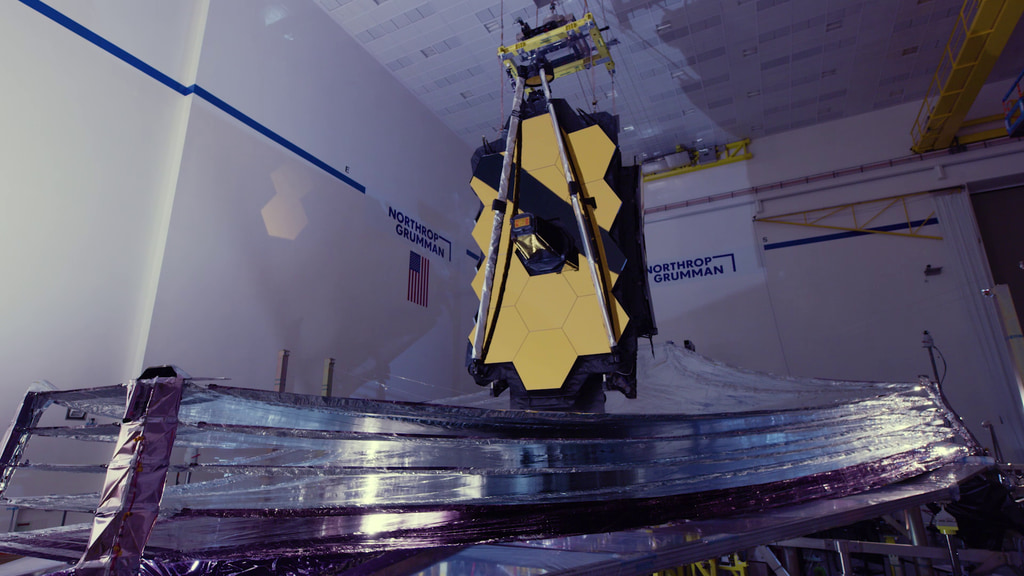

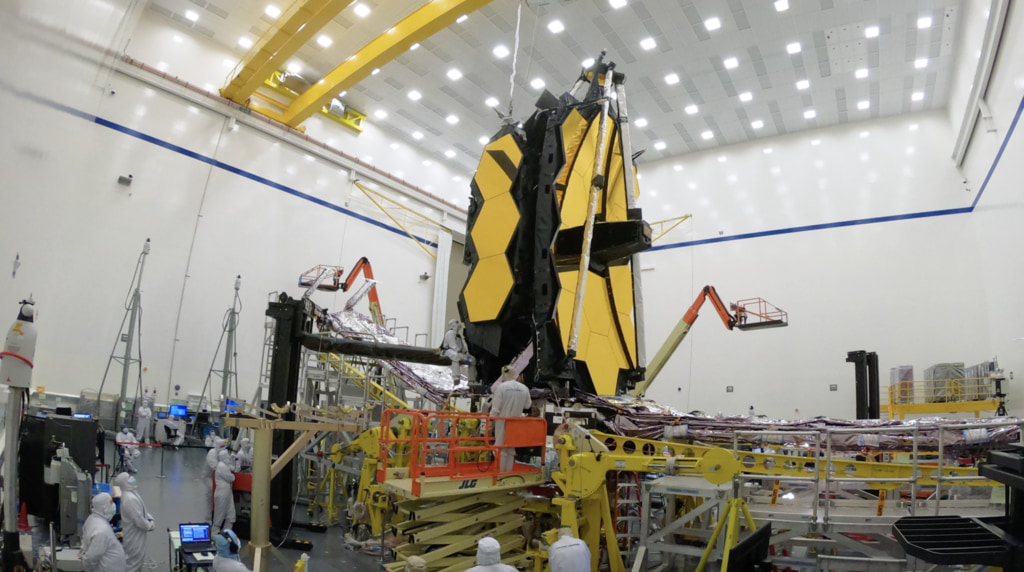

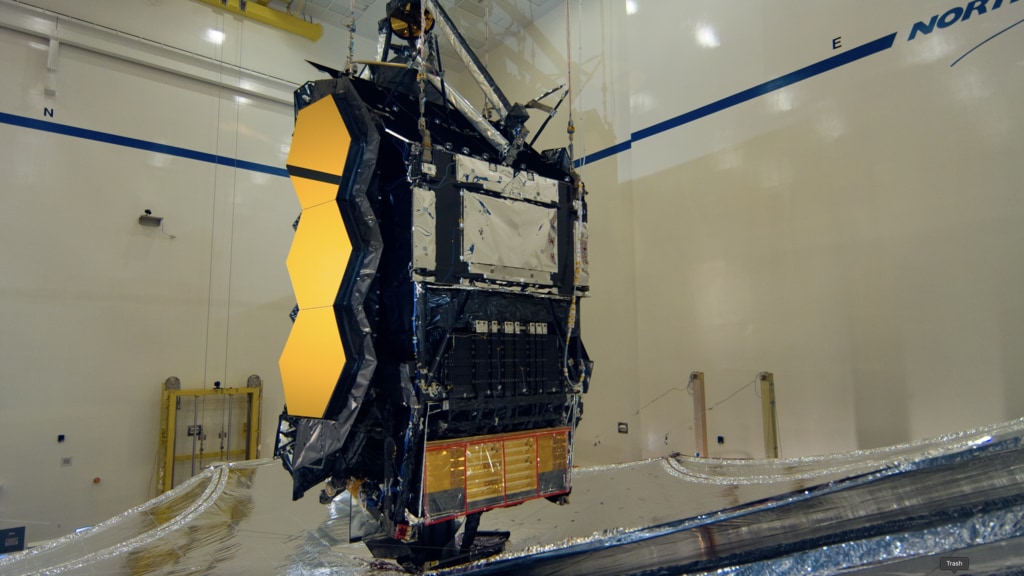

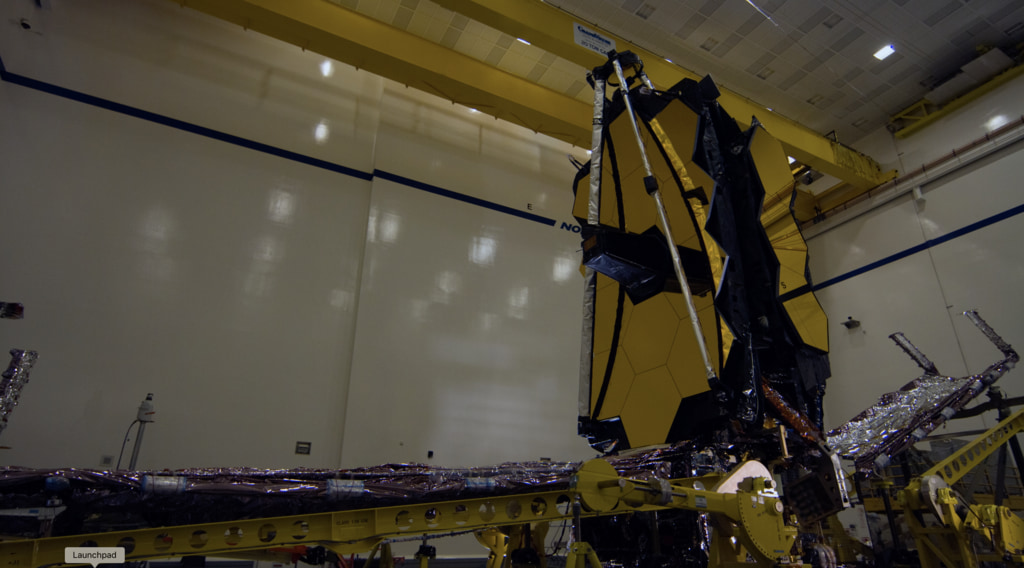

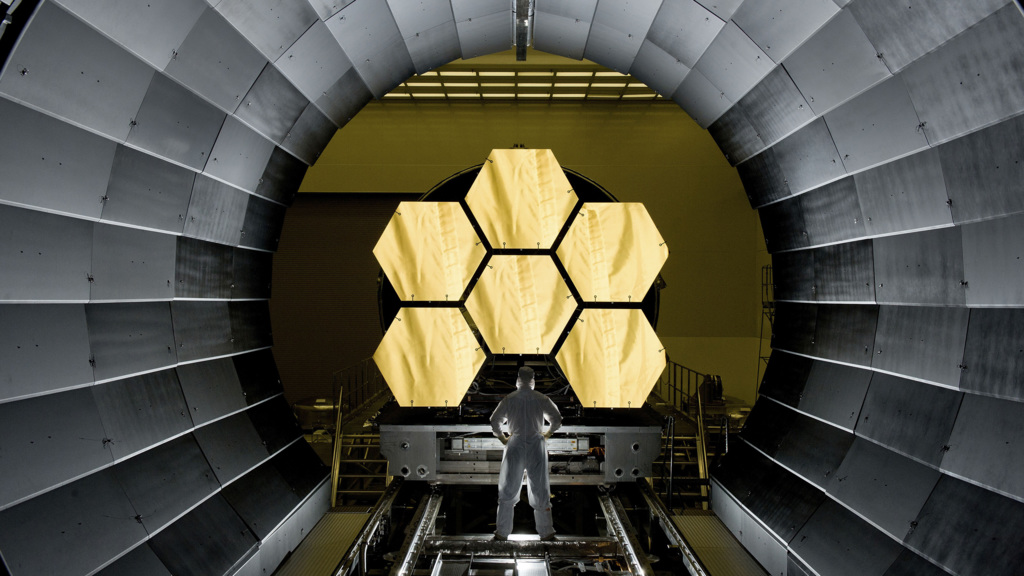

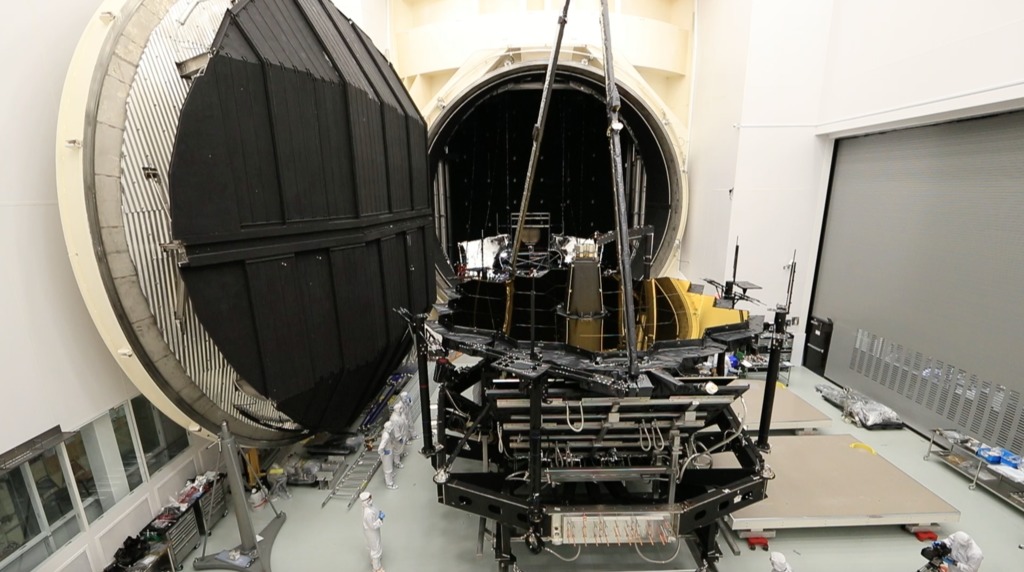

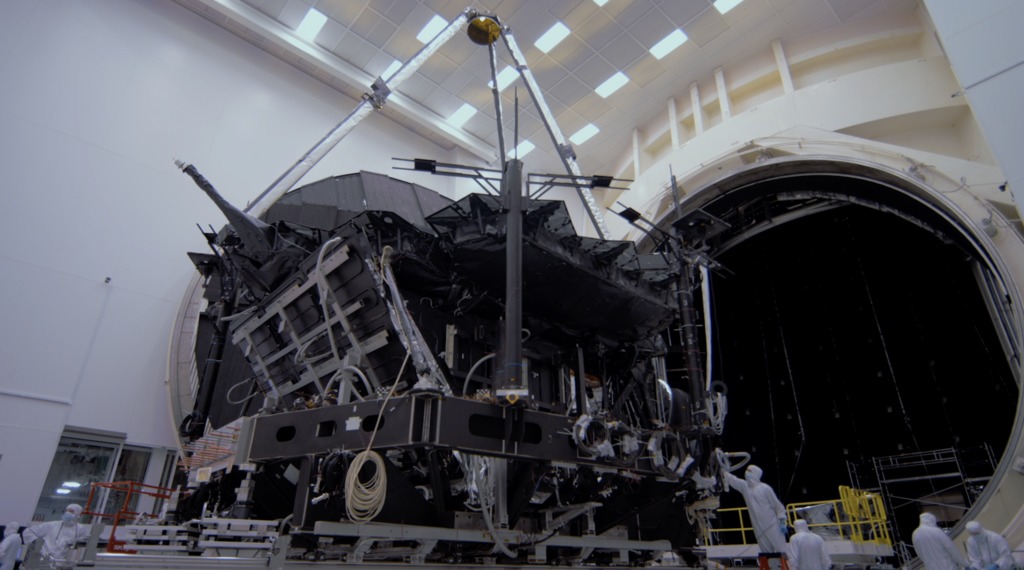

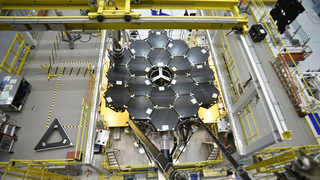

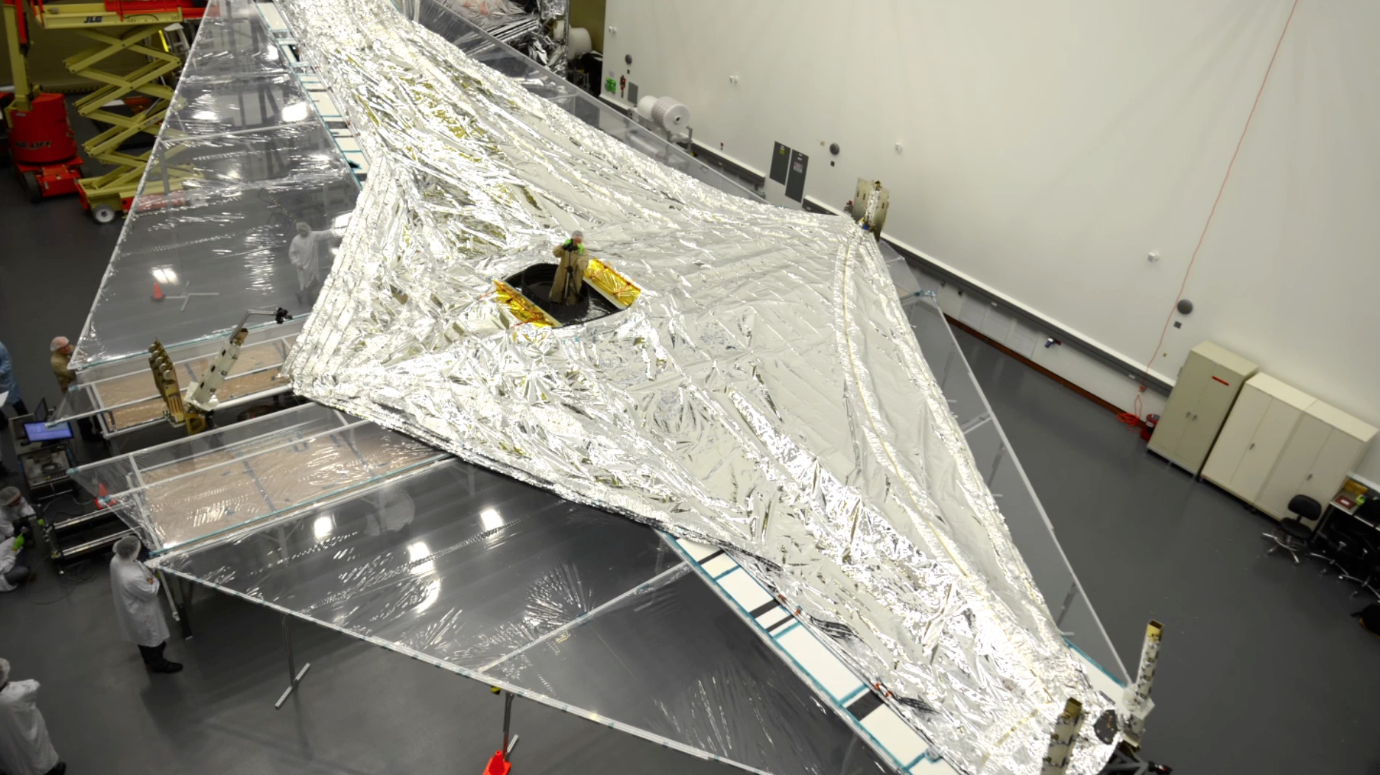

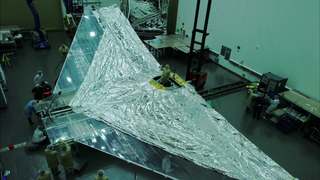

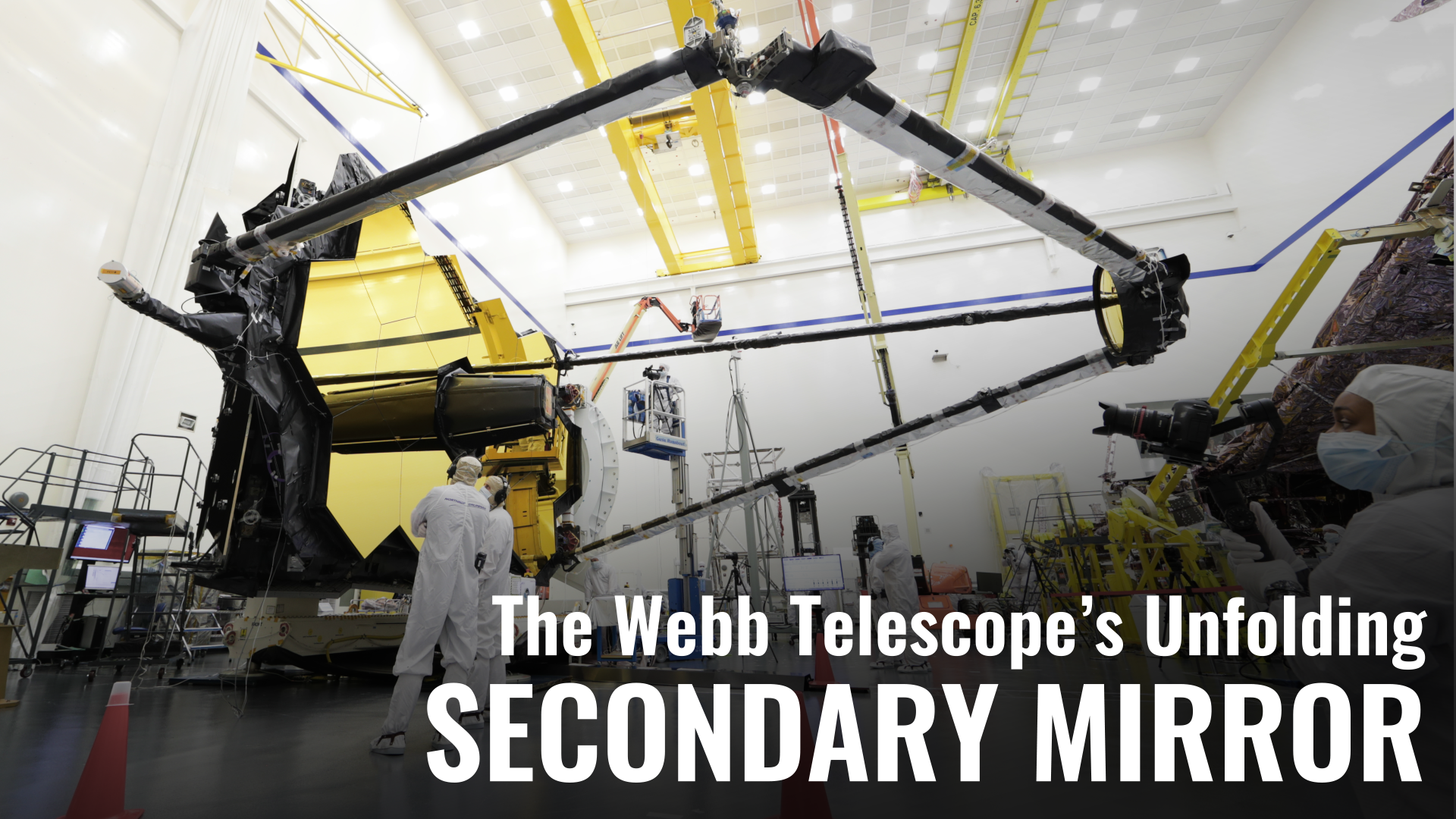

Webb has a large primary mirror, 6.5 meters (21.3 feet) in diameter and a sunshield the size of a tennis court. Both the mirror and sunshade are too large to fit onto the Ariane 5 rocket fully open, so both were folded which meant they needed to be unfolded in space.

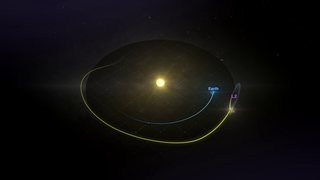

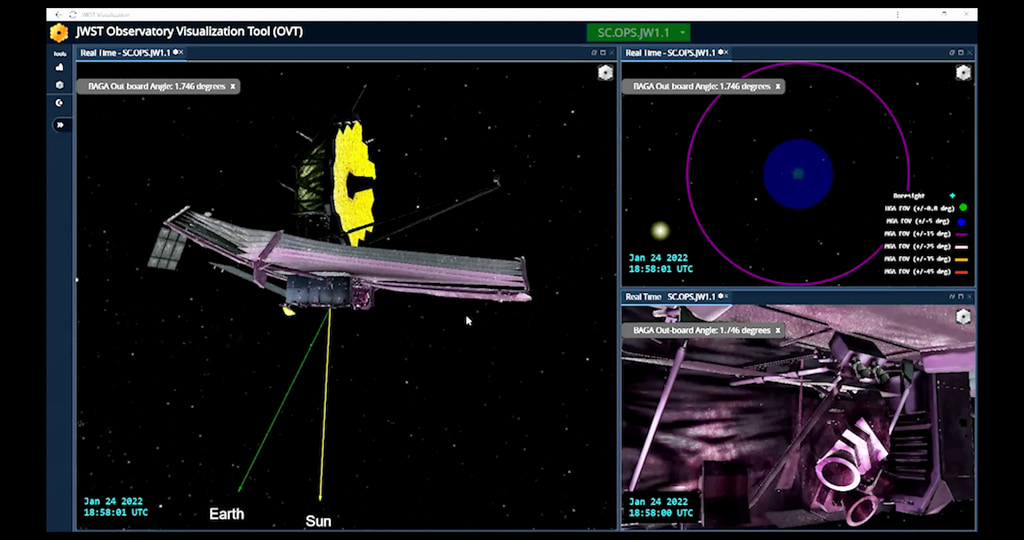

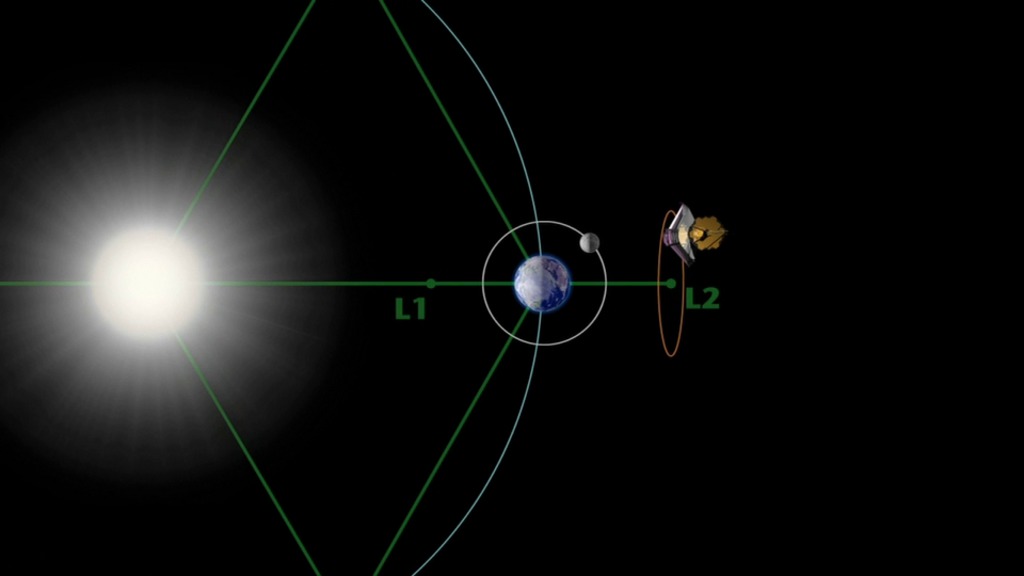

Webb is currently in its operational orbit about 1.5 million km (1 million miles) from the Earth at a location known as Lagrange Point 2 (L2).

The James Webb Space Telescope was named after the NASA Administrator who crafted the Apollo program, and who was a staunch supporter of space science.

Webb First Images

Webb 1st Anniversary Social Media Video

Go to this pageA 90-second social media video celebrating Webb's first year in space. || Webb_1st_Year_Anniversary_Social_Media_Video_2_Copy_010_print.jpg (1024x540) [317.3 KB] || Webb_1st_Year_Anniversary_Social_Media_Video_2_Copy_010.jpg (4096x2160) [1.7 MB] || Webb_1st_Year_Anniversary_Social_Media_Video_2_Copy_010_searchweb.png (320x180) [75.4 KB] || Webb_1st_Year_Anniversary_Social_Media_Video_2_Copy_010_web.png (320x168) [72.1 KB] || Webb_1st_Year_Anniversary_Social_Media_Video_2_Copy_010_thm.png (80x40) [6.6 KB] || Webb_1st_Year_Anniversary_Social_Media_Video.en_US.srt [1.2 KB] || Webb_1st_Year_Anniversary_Social_Media_Video-4K.mov (4096x2160) [4.7 GB] || Webb_1st_Year_Anniversary_Social_Media_Video-h264.mp4 (4096x2160) [110.4 MB] || Webb_1st_Year_Anniversary_Social_Media_Video-h264.webm (4096x2160) [34.7 MB] ||

The James Webb Space Telescope First Image Review Meetings B-Roll

Go to this pageB-roll footage of scientists reviewing the first images from the Webb Space Telescope in the early release obseravation review meetings at the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, MD. ||

The James Webb Space Telescope First Image Release Broadcast July 12, 2022

Go to this pageThe first images taken by the Webb Space Telescope are revealed to the entire world during this broadcast. ||

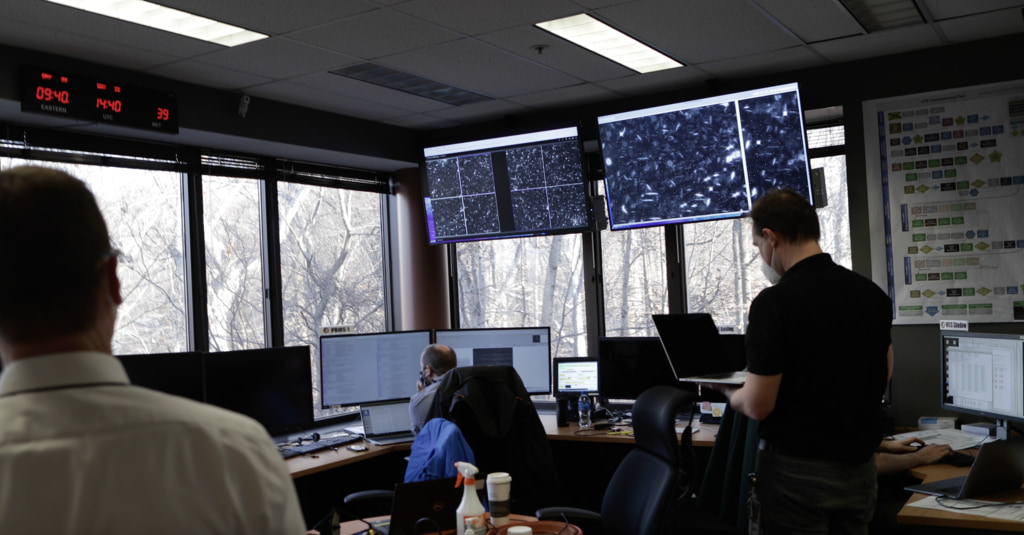

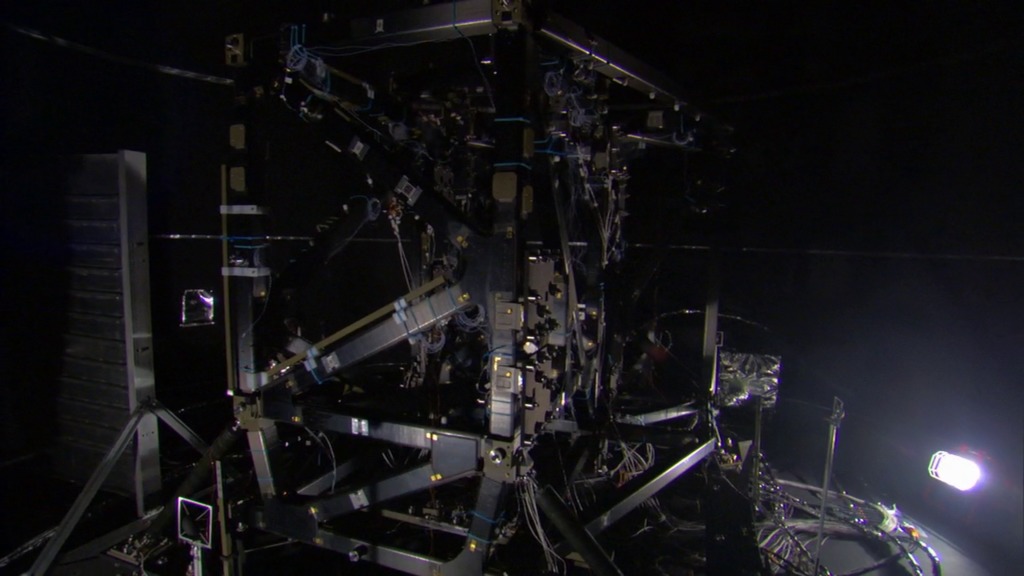

James Webb Mirror Alignment Completion and First Light Staff Meeting Results B-Roll

Go to this pageB-Roll footage of engineers and scientists completing the mirror alignment on the James Webb Space Telescope an a staff meeting to witness the final result of the tests at the Space Telescop Science Institute in Baltimore, MD. ||

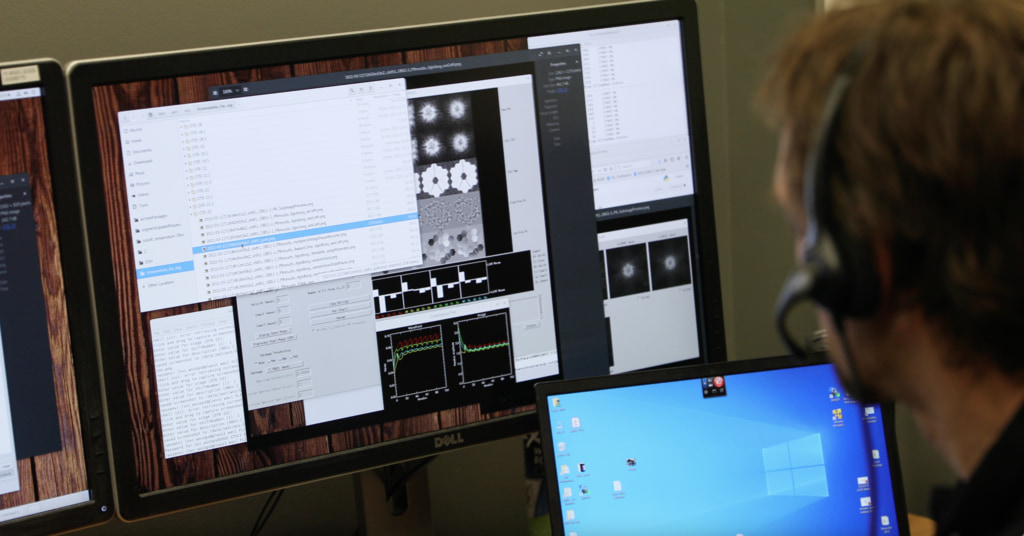

The James Webb Space Telescope First Star 18 Times B-roll

Go to this pageB-roll footage of engineers and scientists working to align of the mirrors on the primary mirror of the James Webb Space Telescope at the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, MD. ||

Webb Media Resource Highlights

Webb Telescope Launch Highlights

Go to this pageWebb Telescope Launch Highlights || 14062_Webb_Launch_Highlights_pic.jpg (2552x1440) [336.5 KB] || 14062_Webb_Launch_Highlights_pic_searchweb.png (180x320) [77.2 KB] || 14062_Webb_Launch_Highlights_pic_thm.png (80x40) [10.2 KB] || 14062_Webb_Launch_Highlights.mov (1280x720) [7.7 GB] || 14062_Webb_Launch_Highlights.mp4 (1280x720) [896.0 MB] || 14062_Webb_Launch_Highlights.webm (1280x720) [93.3 MB] || Webb Launch Broadcast Highlights - December 25, 2021 ||

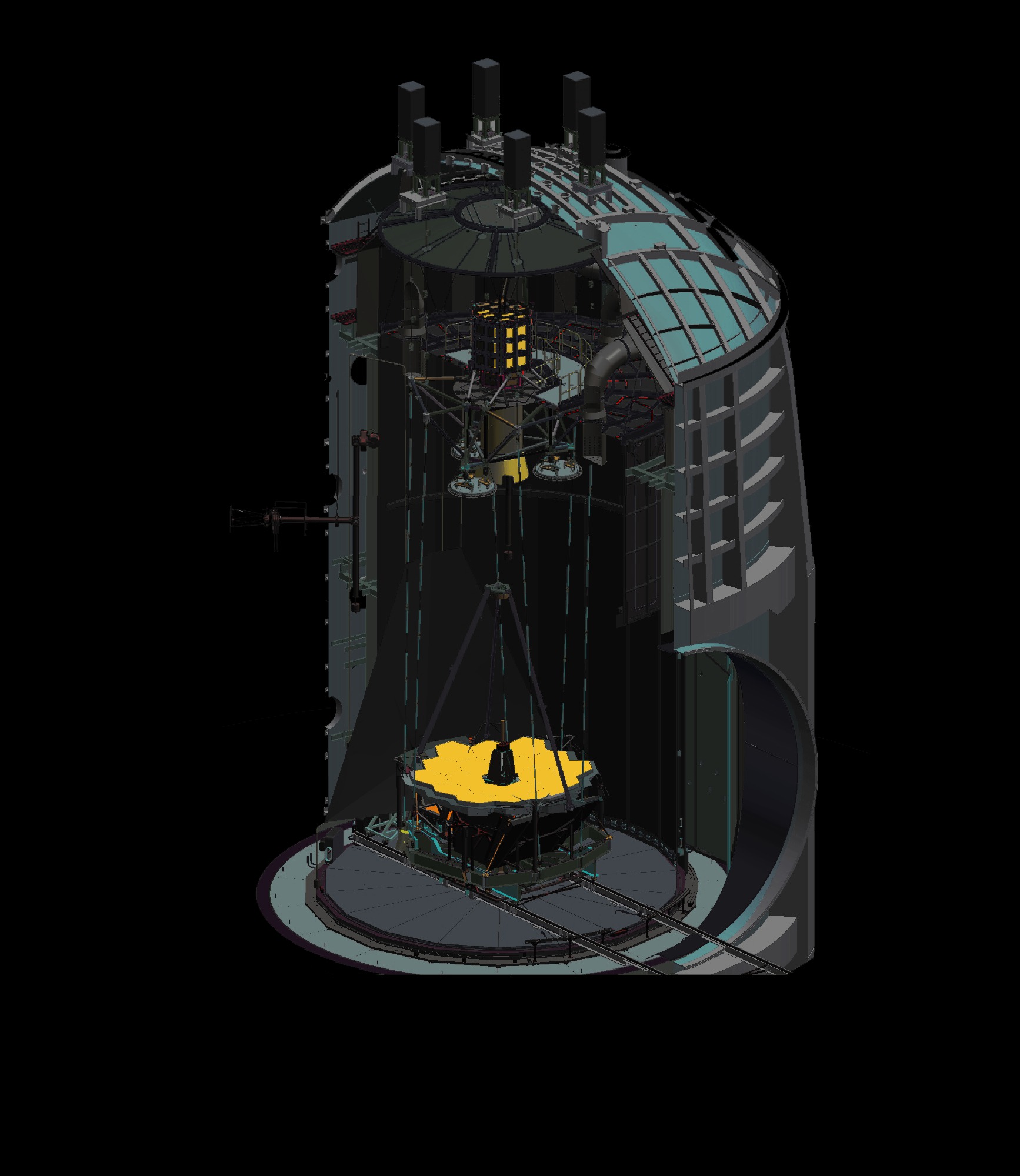

Webb Deployment Animations

Go to this pageThese animation show the James Webb Space Telescope deployment sequence, as well as breakout animations of each major deployment on the telescope.Each animation is available as a Quicktime ProRes, mpeg-4 or as a png frames sequence. ||

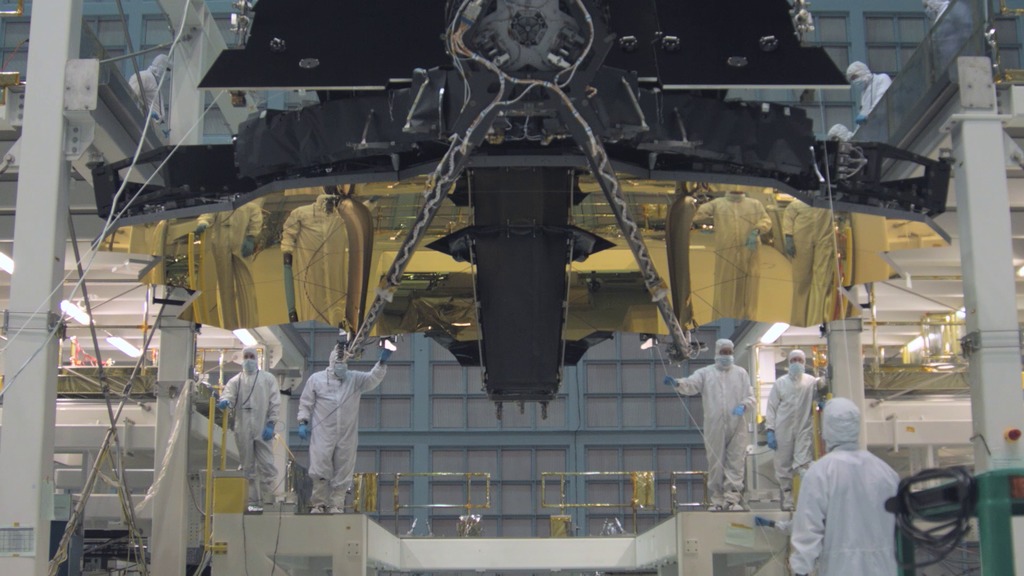

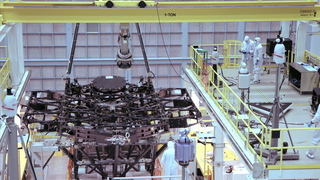

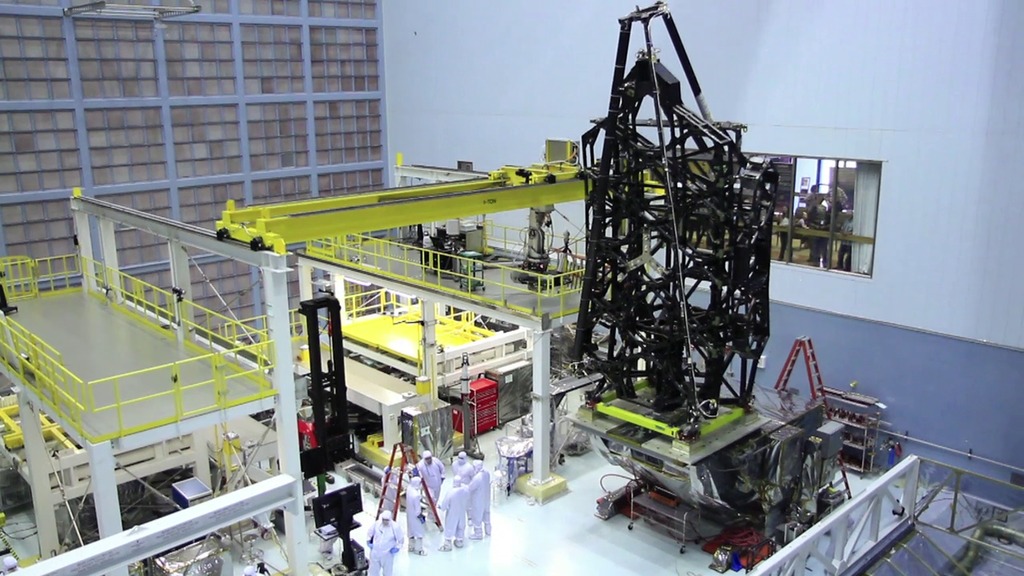

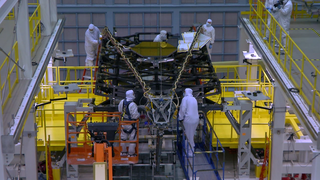

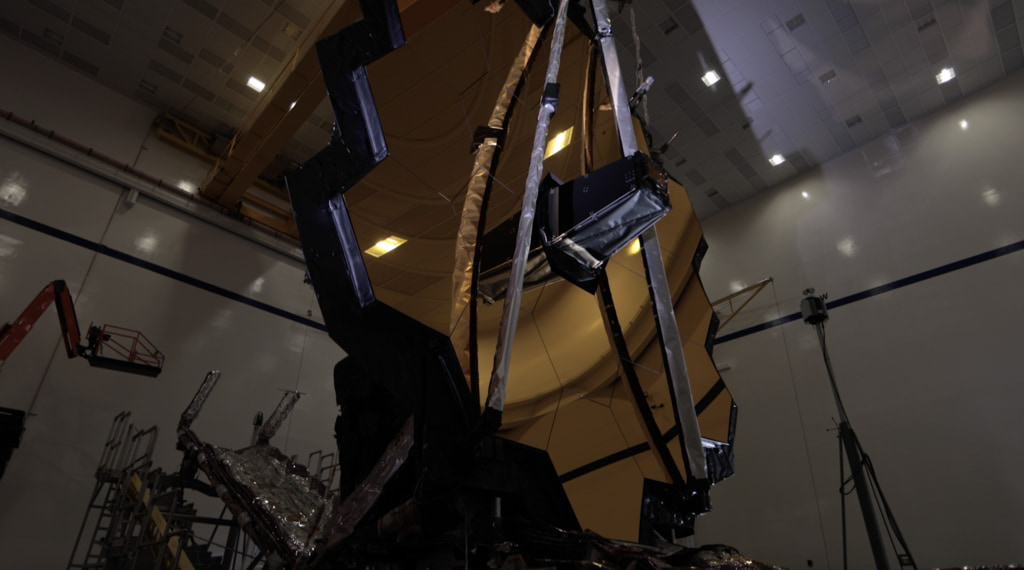

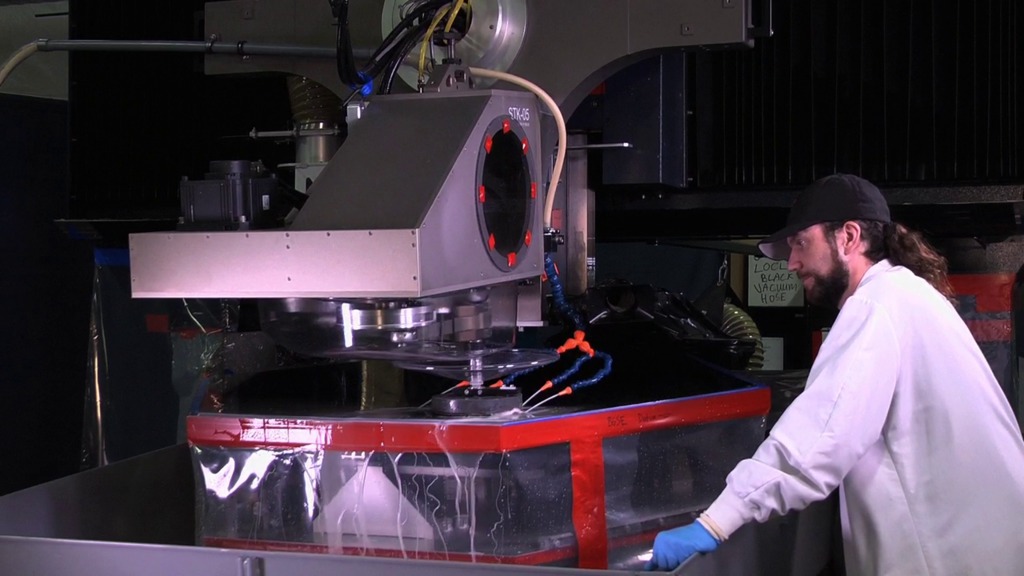

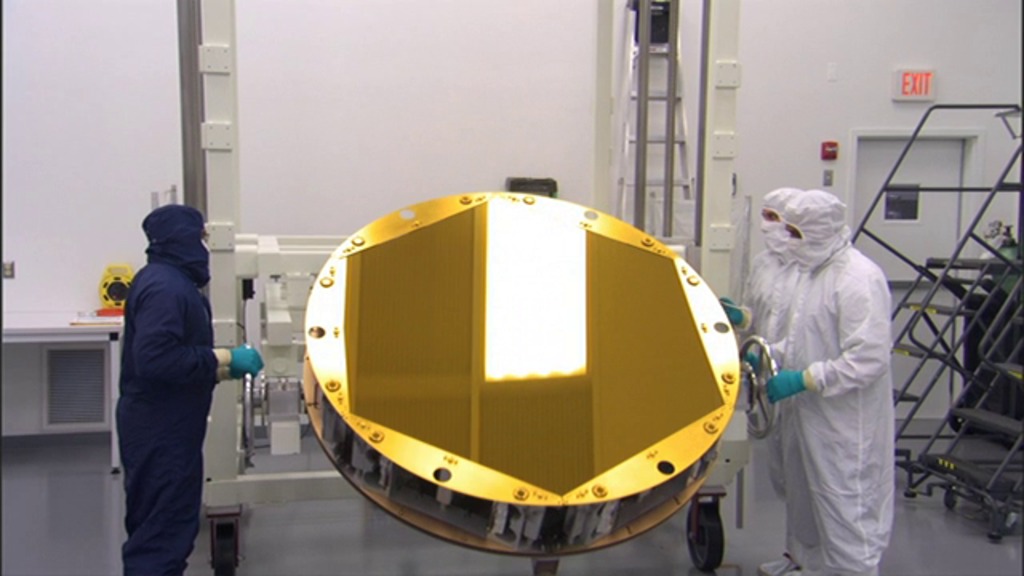

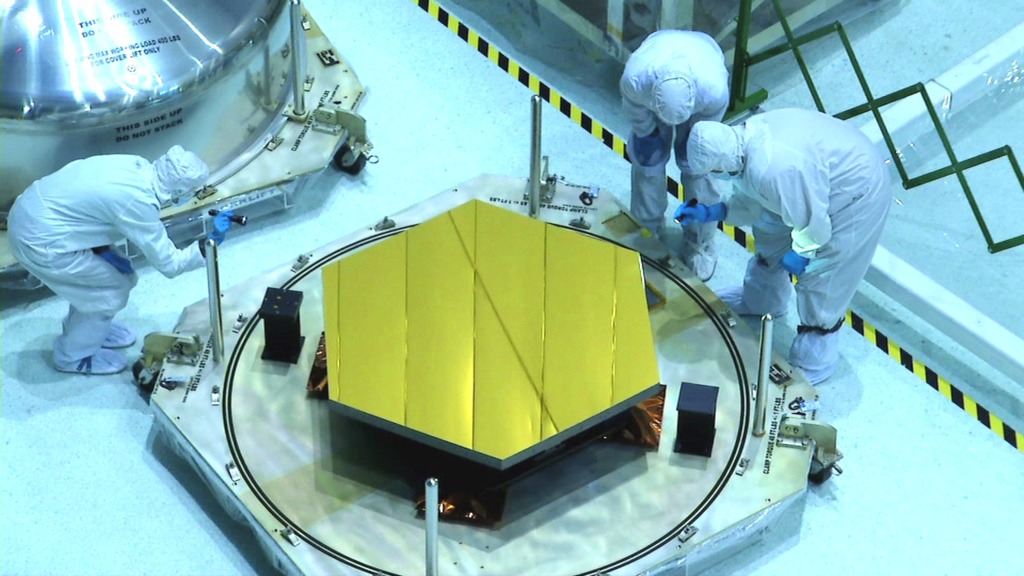

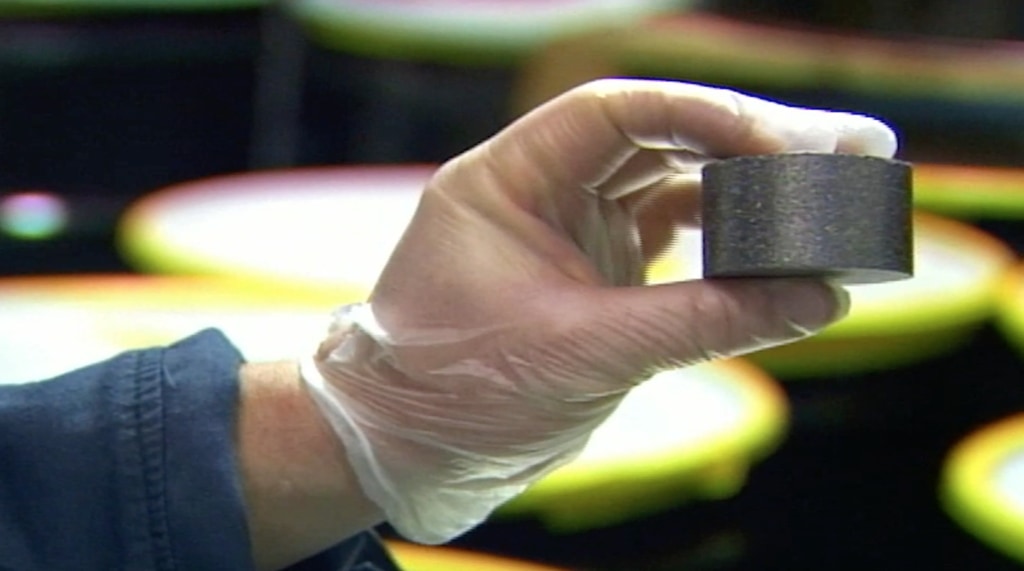

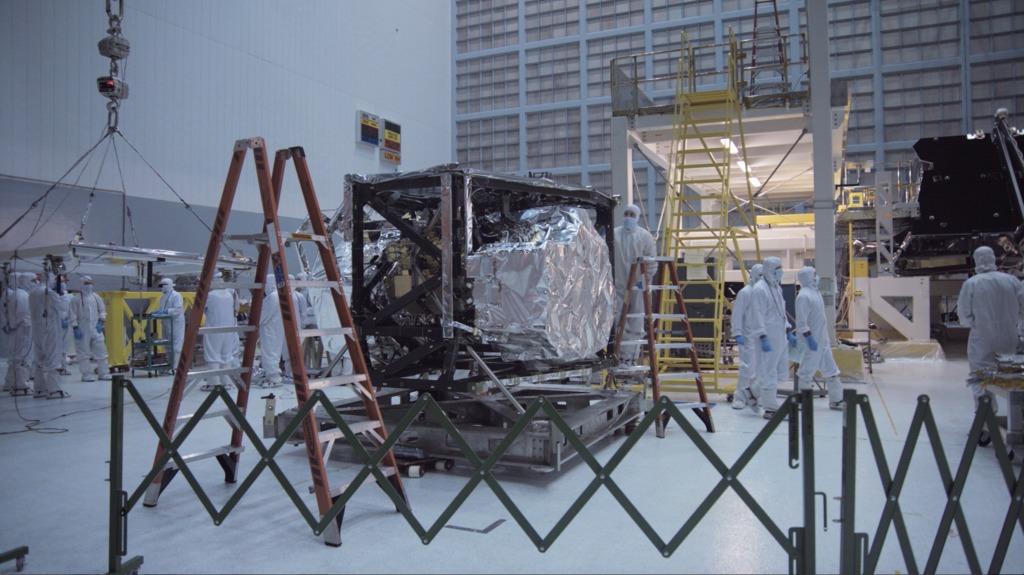

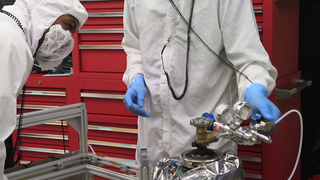

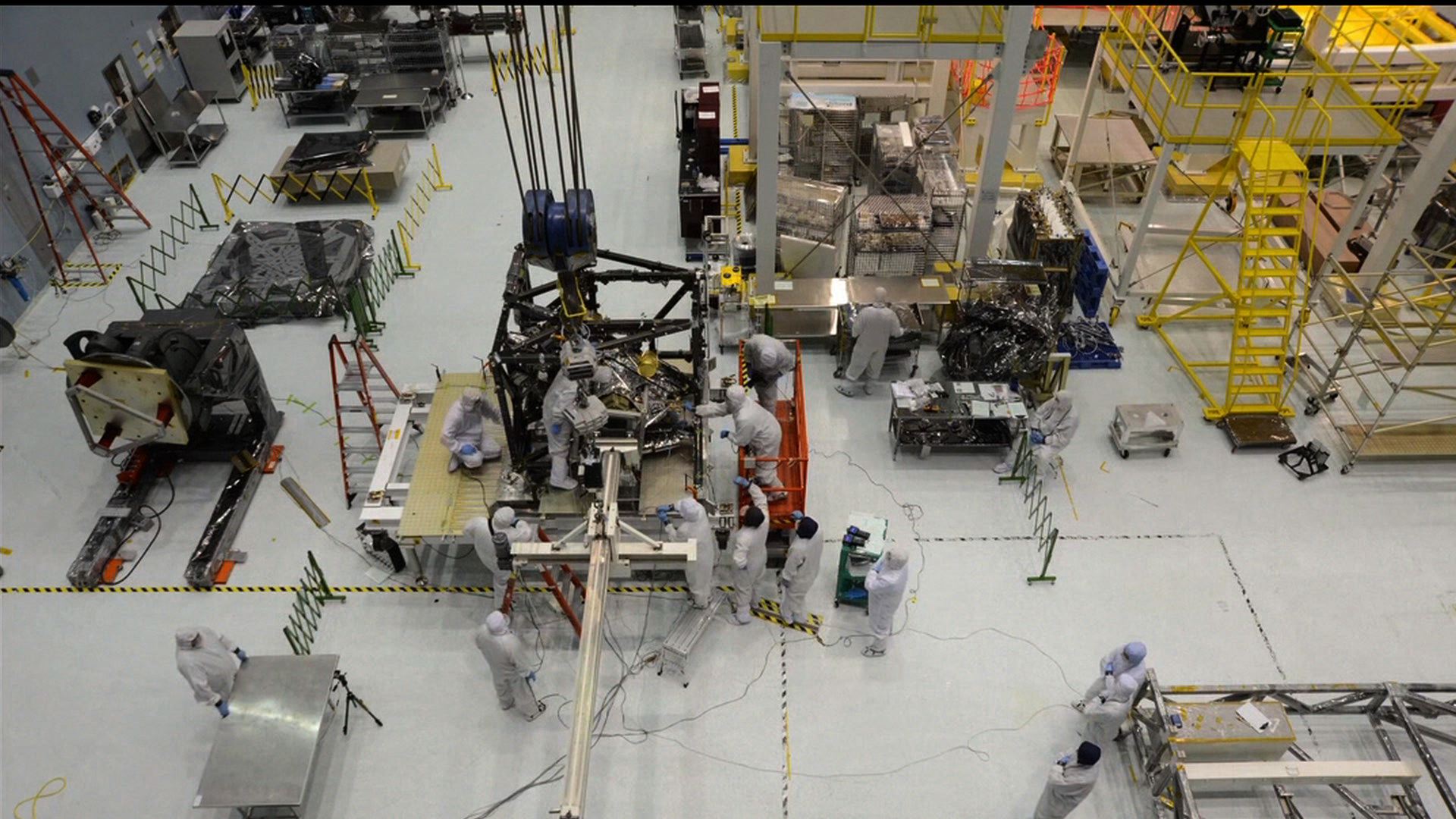

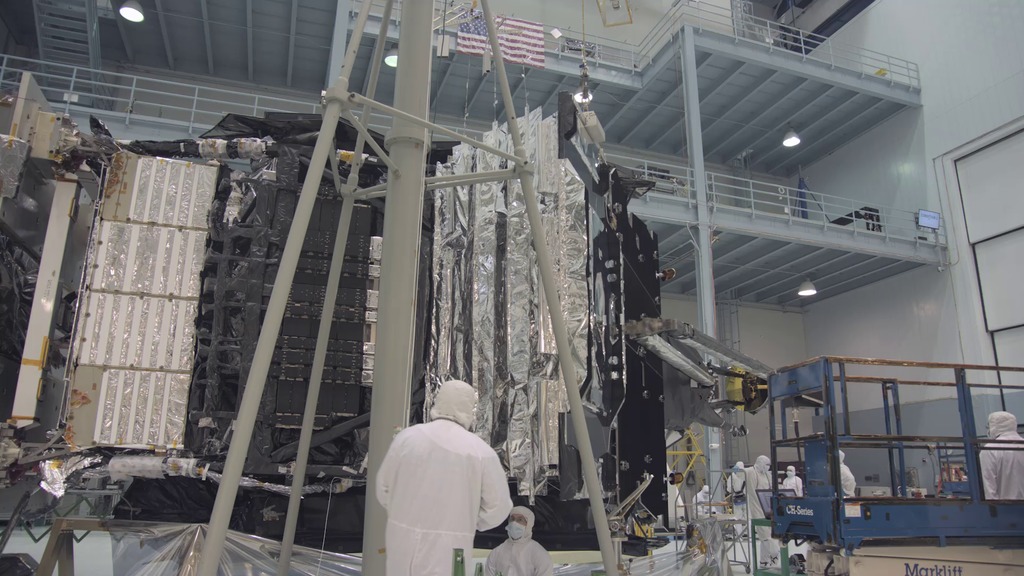

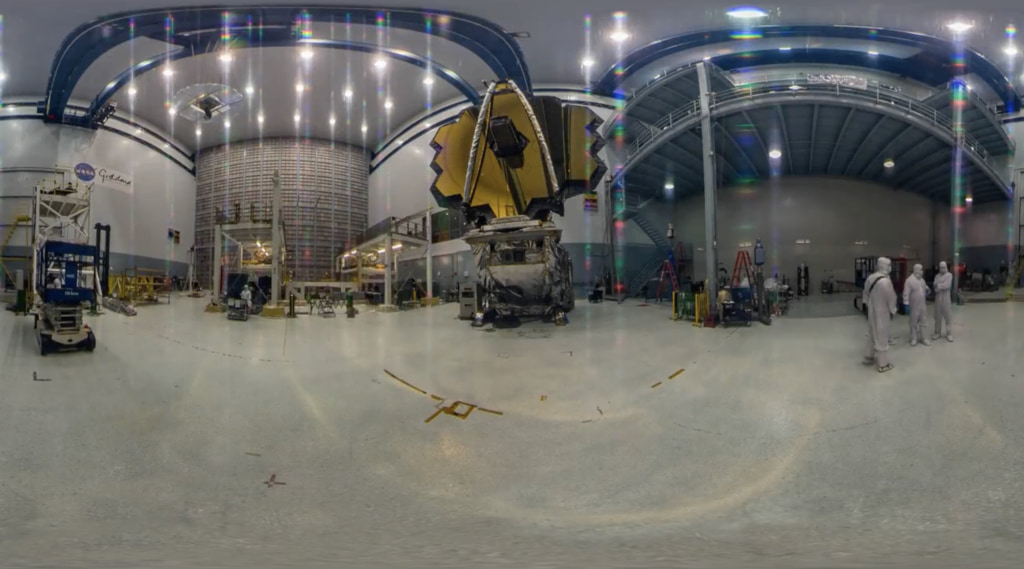

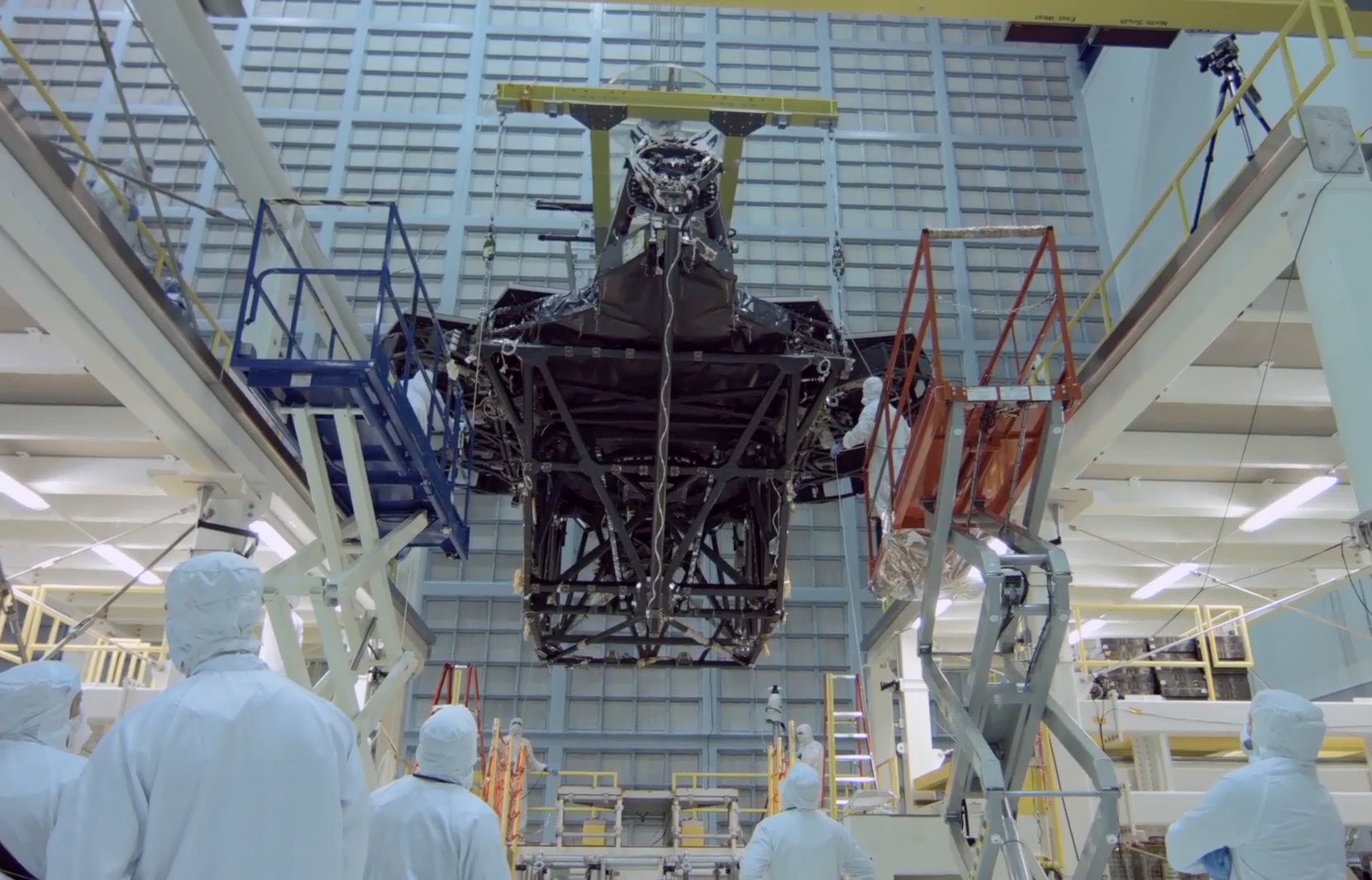

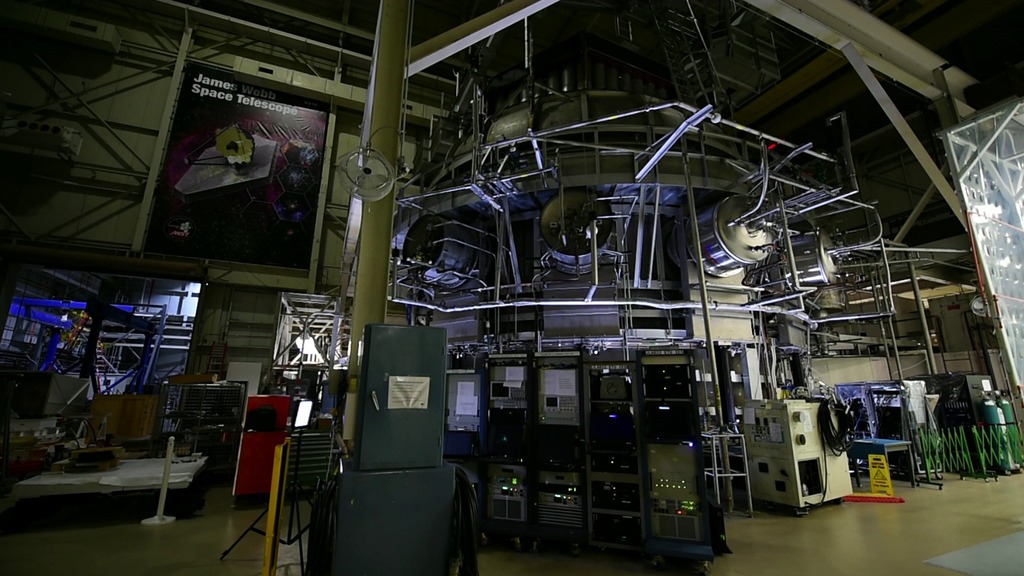

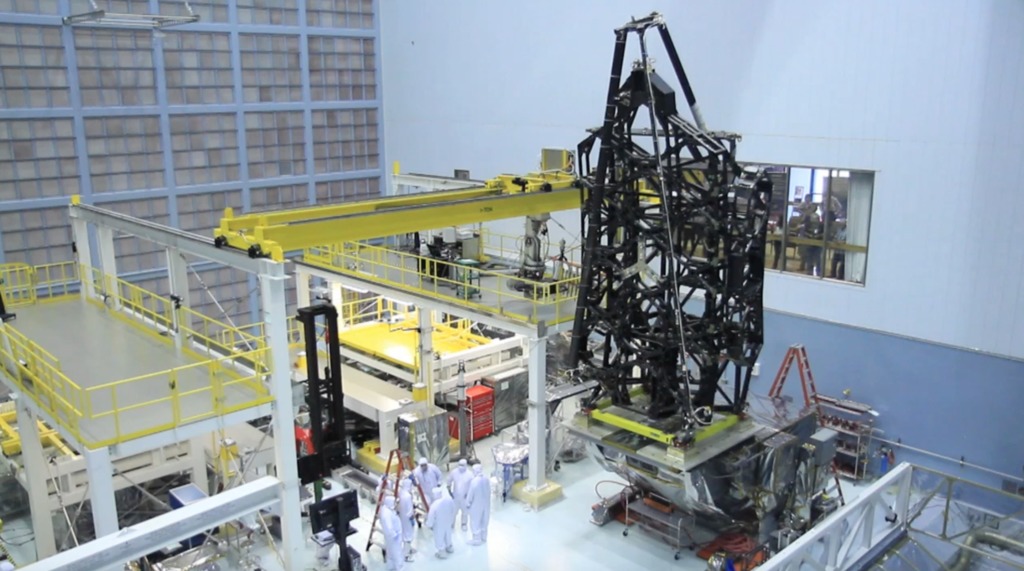

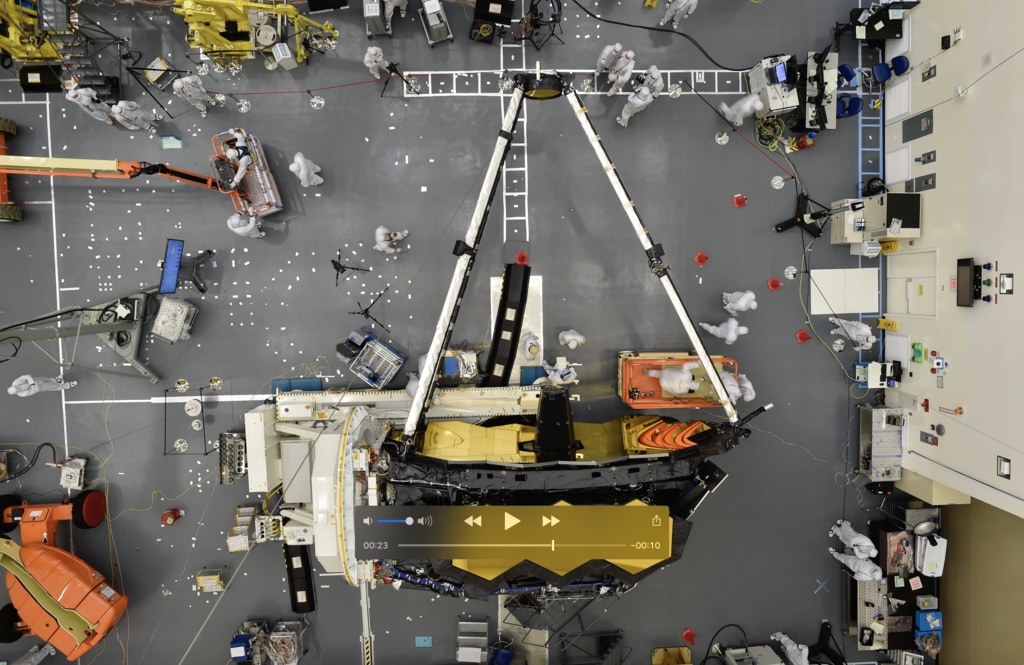

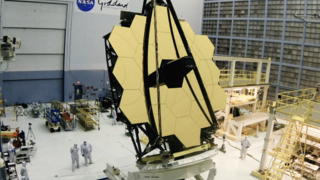

James Webb Space Telescope Media Resource B-roll & Time-Lapse Reel

Go to this pageA media reel of b-roll and time-lapse footage of the James Webb Space Telescope. || Screen_Shot_2020-10-29_at_2.23.22_PM_print.jpg (1024x575) [180.1 KB] || Screen_Shot_2020-10-29_at_2.23.22_PM.png (3348x1880) [7.6 MB] || Screen_Shot_2020-10-29_at_2.23.22_PM_searchweb.png (180x320) [112.8 KB] || Screen_Shot_2020-10-29_at_2.23.22_PM_thm.png (80x40) [11.1 KB] || JWST_Media_Resource_B-roll_Reel_1080p_B.mov (1920x1080) [7.2 GB] || JWST_Media_Resource_B-roll_Reel_1080p_B.mp4 (1920x1080) [524.4 MB] || JWST_Media_Resource_B-roll_Reel_1080p_B.webmhd.webm (1080x606) [103.8 MB] ||

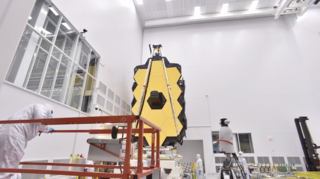

James Webb Space Telescope Media Resource Beauty Shots Reel

Go to this pageA media reel of beauty shots of the James Webb Space Telescope. || Screen_Shot_2020-10-30_at_11.47.40_AM_print.jpg (1024x574) [160.8 KB] || Screen_Shot_2020-10-30_at_11.47.40_AM.png (3340x1874) [8.8 MB] || Screen_Shot_2020-10-30_at_11.47.40_AM_searchweb.png (320x180) [98.3 KB] || Screen_Shot_2020-10-30_at_11.47.40_AM_thm.png (80x40) [10.4 KB] || JWST_Media_Resource_Beauty_Shots_Reel_1080p_B.webm (1920x1080) [10.1 MB] || JWST_Media_Resource_Beauty_Shots_Reel_1080p_B.mp4 (1920x1080) [103.8 MB] || JWST_Media_Resource_Beauty_Shots_Reel_1080p_B.mov (1920x1080) [1.5 GB] ||

James Webb Space Telescope Media Resource Animation Reel

Go to this pageA media reel of animations regarding the James Webb Space Telescope. || Screen_Shot_2020-10-29_at_2.27.33_PM_print.jpg (1024x574) [62.9 KB] || Screen_Shot_2020-10-29_at_2.27.33_PM.png (3346x1876) [3.3 MB] || Screen_Shot_2020-10-29_at_2.27.33_PM_searchweb.png (320x180) [55.8 KB] || Screen_Shot_2020-10-29_at_2.27.33_PM_thm.png (80x40) [7.4 KB] || JWST_Media_Resource_Animation_Reel_1080p_A2.mov (1920x1080) [4.2 GB] || JWST_Media_Resource_Animation_Reel_1080p_A2.mp4 (1920x1080) [332.5 MB] || JWST_Media_Resource_Animation_Reel_1080p_A2.webm (1920x1080) [32.3 MB] ||

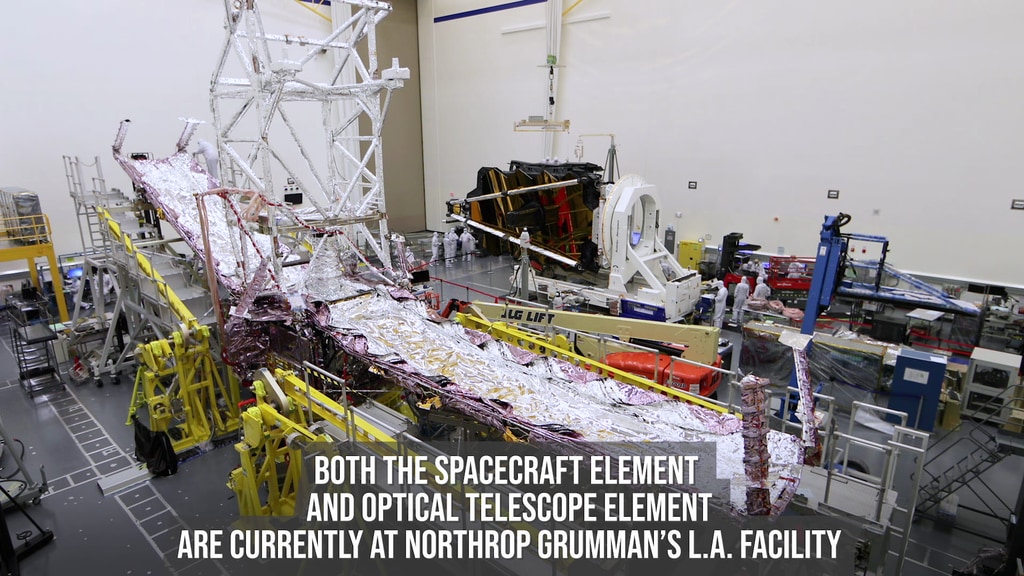

James Webb Space Telescope Update B-Roll

Go to this pageWebb Telescope assembly b-roll and animations || THUMBNAIL_ONLY-Webb_Assembly-video-file-b-roll.jpg (1920x1080) [1.1 MB] || THUMBNAIL_ONLY-Webb_Assembly-video-file-b-roll_print.jpg (1024x576) [511.0 KB] || THUMBNAIL_ONLY-Webb_Assembly-video-file-b-roll_searchweb.png (320x180) [114.2 KB] || THUMBNAIL_ONLY-Webb_Assembly-video-file-b-roll_thm.png (80x40) [8.0 KB] || Webb_Assembly-video-file-b-roll.mov (1920x1080) [6.5 GB] || Webb_Assembly-video-file-b-roll-h264.mp4 (1920x1080) [510.5 MB] || Webb_Assembly-video-file-b-roll.webm (1920x1080) [52.4 MB] ||

Recent Releases

- Produced Video

- B-Roll

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Animation

- Produced Video

- Section

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- B-Roll

- Produced Video

- B-Roll

- Produced Video

- Section

Webb Launch and Deployment Programs and Highlights

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Section

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

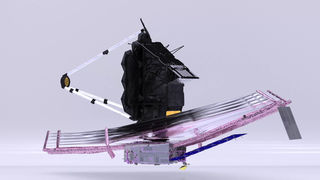

Spacecraft Animation

- Animation

- Animation

- Produced Video

- Section

- Section

- Animation

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Animation

- Section

- Section

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Animation

- Animation

Science Animation

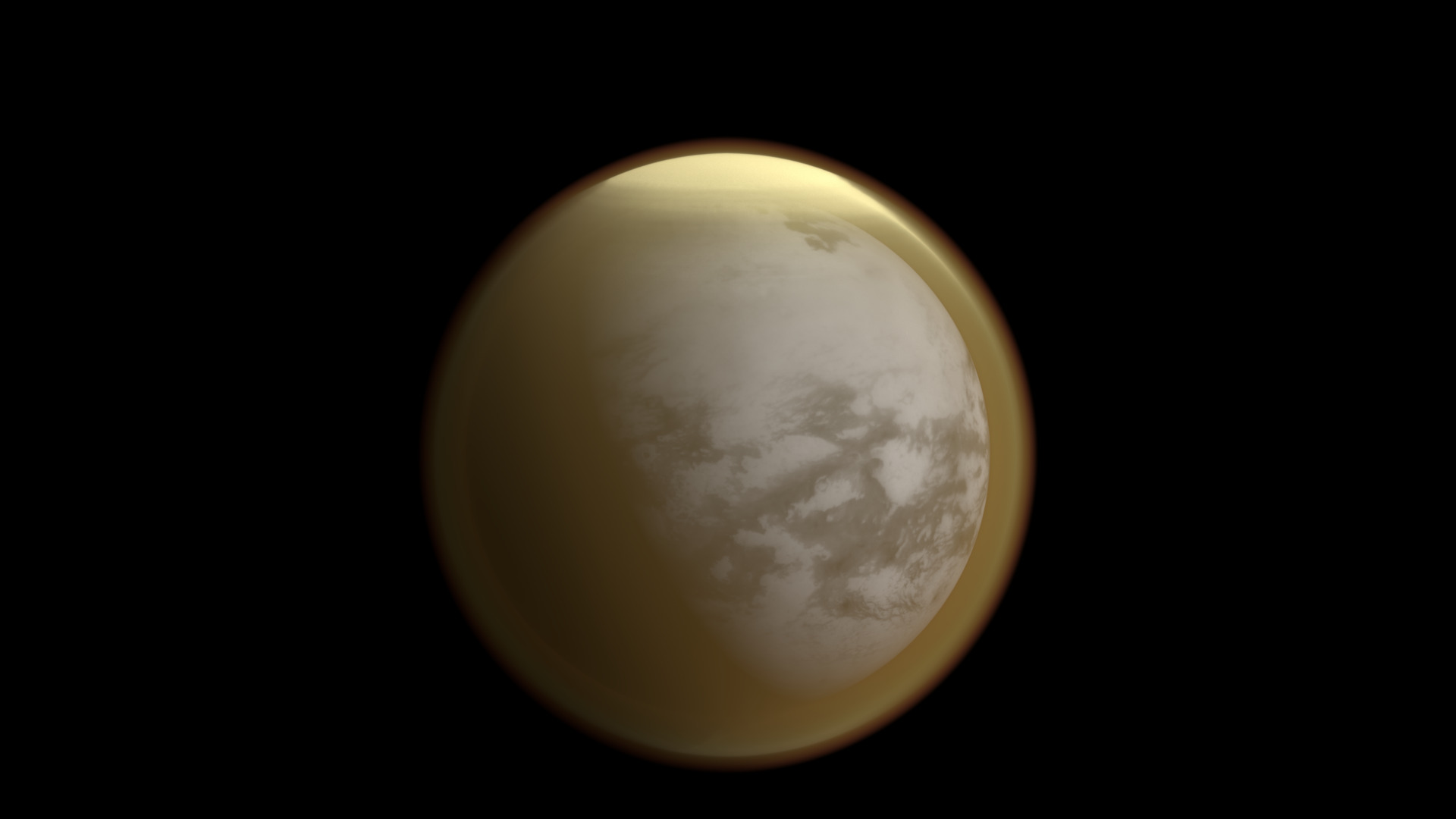

Titan science results from James Webb Space Telescope: animation resource page

Go to this pagePush into JWST to Saturn and Titan. || JWST_Titan_Intro_Final_V001.00957_print.jpg (1024x576) [145.8 KB] || JWST_Titan_Intro_Final_V001.00957_searchweb.png (320x180) [78.0 KB] || JWST_Titan_Intro_Final_V001.00957_thm.png [5.5 KB] || JWST_Titan_Intro_Final_1080.mp4 (1920x1080) [72.8 MB] || JWST_Titan_Intro_Final_V001.mp4 (3840x2160) [38.4 MB] || JWST_Titan_Intro_Final_V001.mov (3840x2160) [6.8 GB] ||

Webb Confirms Seasonal Variations in Titan Climate Model

Go to this pageThis global circulation model simulates a year of weather on Titan, depicting seasonal variations in wind currents, methane cloud cover, and sunlight over the course of a Saturn year (approximately 29.5 Earth years). New observations from the James Webb Science Telescope confirm this seasonal variation.

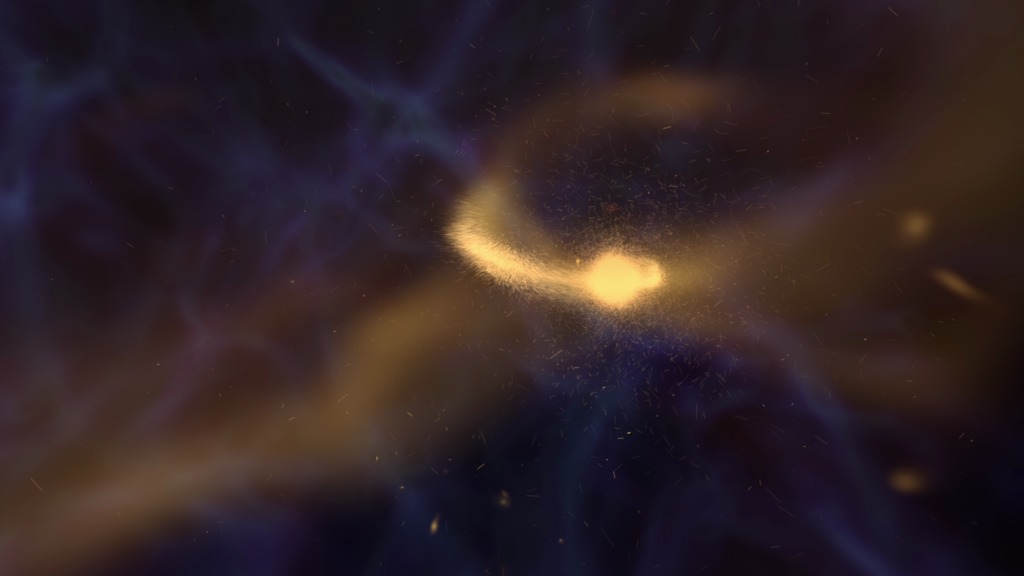

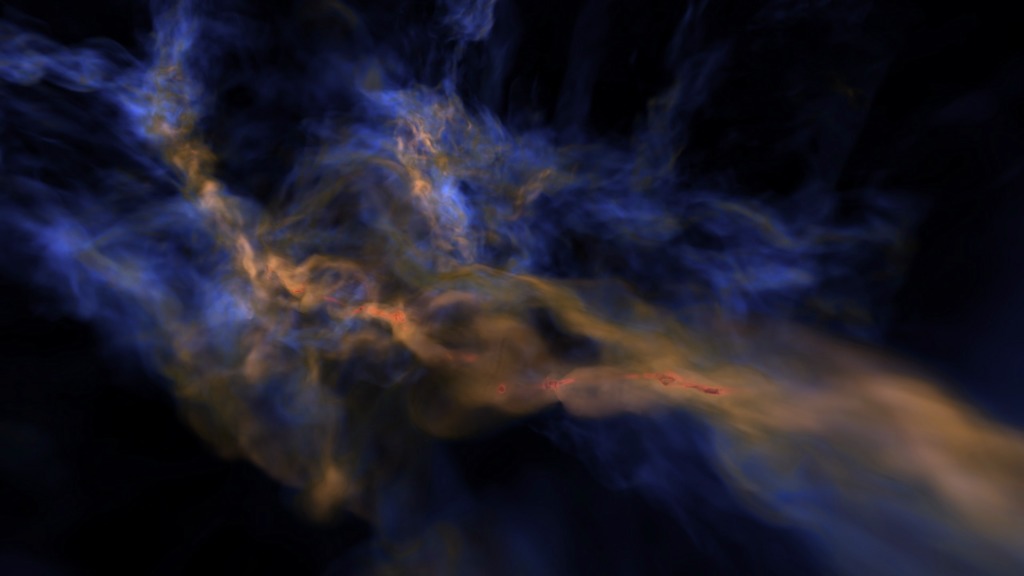

Webb Science Simulations: Re-Ionization Era

Go to this pageThe visualization shows galaxies, composed of gas, stars and dark matter, colliding and forming filaments in the large-scale universe providing a view of the Cosmic Web. The Advanced Visualization Laboratory (AVL) at the National Center for Supercomputing Applications (NCSA) collaborated with NASA and Drs. Renyue Cen and Jeremiah Ostriker to visualize a simulation of the nonlinear cosmological evolution of the universe. Drs. Cen and Ostriker developed one of the largest cosmological hydrodynamic simulations and computed over 749 gigabytes of raw data at the NCSA in 2005. AVL used Amore software (http://avl.ncsa.illinois.edu/what-we-do/software) to interpolate and render approximately 322 gigabytes of a subset of the computed data. The simulation begins about 20 million years after the Big Bang - about 13.7 billion years ago - and extends until the present day.AVL(http://avl.ncsa.illinois.edu/) at NCSA (http://ncsa.illinois.edu/), University of Illinois (www.illinois.edu) ||

JWST Science Simulations: Galaxy Formation

Go to this pageSupercomputer Simulations of Galaxy Formation and Evolution. This visualization shows small galaxies forming, interacting, and merging to make ever-larger galaxies. This 'hierarchical structure formation' is driven by gravity and results in the creation of galaxies with spiral arms much like our own Milky Way galaxy. The Adaptive Mesh Refinement (AMR) simulation generated from ENZO code for cosmology and astrophysics was developed by Drs. Brian O'Shea and Michael Norman. The AMR code generated 1.8 terabytes of data and was computed at NCSA. AVL used Amore software (http://avl.ncsa.illinois.edu/what-we-do/software) to interpolate and render 2700 frames (42 gigabytes of HD images). The simulation spans a time period of 13.7 billion years. This visualization provides insight into the assembly and formation of galaxies. James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) will probe the earliest periods of galaxy formation by looking deep into space to see the first galaxies that form in the universe, only a few hundred million years after the Big Bang. The Advanced Visualization Laboratory (AVL) at the National Center for Supercomputing Applications (NCSA) collaborated with NASA and Drs. Brian O'Shea and Michael Norman to visualize the formation of a Milky Way-type galaxy. The Adaptive Mesh Refinement (AMR) simulation generated from ENZO code for cosmology and astrophysics was developed by Drs. Brian O'Shea and Michael Norman. The AMR code generated 1.8 terabytes of data and was computed at NCSA. AVL used Amore software (http://avl.ncsa.illinois.edu/what-we-do/software) to interpolate and render 2700 frames (42 gigabytes of HD images). The simulation spans a time period of 13.7 billion years. This visualization provides insight into the assembly and formation of galaxies. James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) will probe the earliest periods of galaxy formation by looking deep into space to see the first galaxies that form in the universe, only a few hundred million years after the Big Bang.AVL(http://avl.ncsa.illinois.edu/) at NCSA (http://ncsa.illinois.edu/), University of Illinois (www.illinois.edu) ||

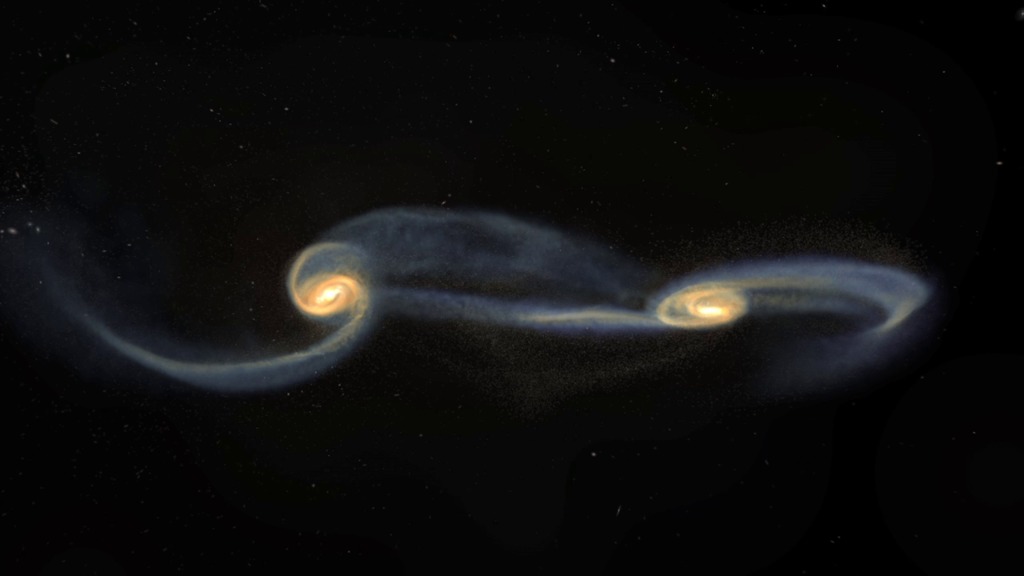

JWST Science Simulation: Galaxy Collision

Go to this pageThe Advanced Visualization Laboratory (AVL) at the National Center for Supercomputing Applications (NCSA) collaborated with NASA and Drs. Brant Robertson and Lars Hernquist to visualize two colliding galaxies that interact and merge into a single elliptical galaxy over a period spanning two billion years of evolution. The scientific theoretical model and the computational data output were developed by Drs. Brant Robertson and Lars Hernquist. AVL rendered more than 80 gigabytes of this data using in-house rendering software and Virtual Director for camera choreography. This computation provides important research to understand galaxy mergers, and the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) will provide data to test such theories. When two large disk-shaped galaxies merge — as will happen within the next few billion years with the Milky Way galaxy and its largest neighbor, the Andromeda Galaxy — the result will likely settle into a cloud-shaped elliptical galaxy. Most elliptical galaxies observed today formed from collisions that occurred billions of years ago. It is difficult to observe such collisions now with ground-based telescopes since these collisions are billions of light-years away. JWST will probe in unprecedented detail those distant epochs, and provide exquisite images of mergers caught in the act of destroying disk galaxies.AVL at NCSA University of Illinois ||

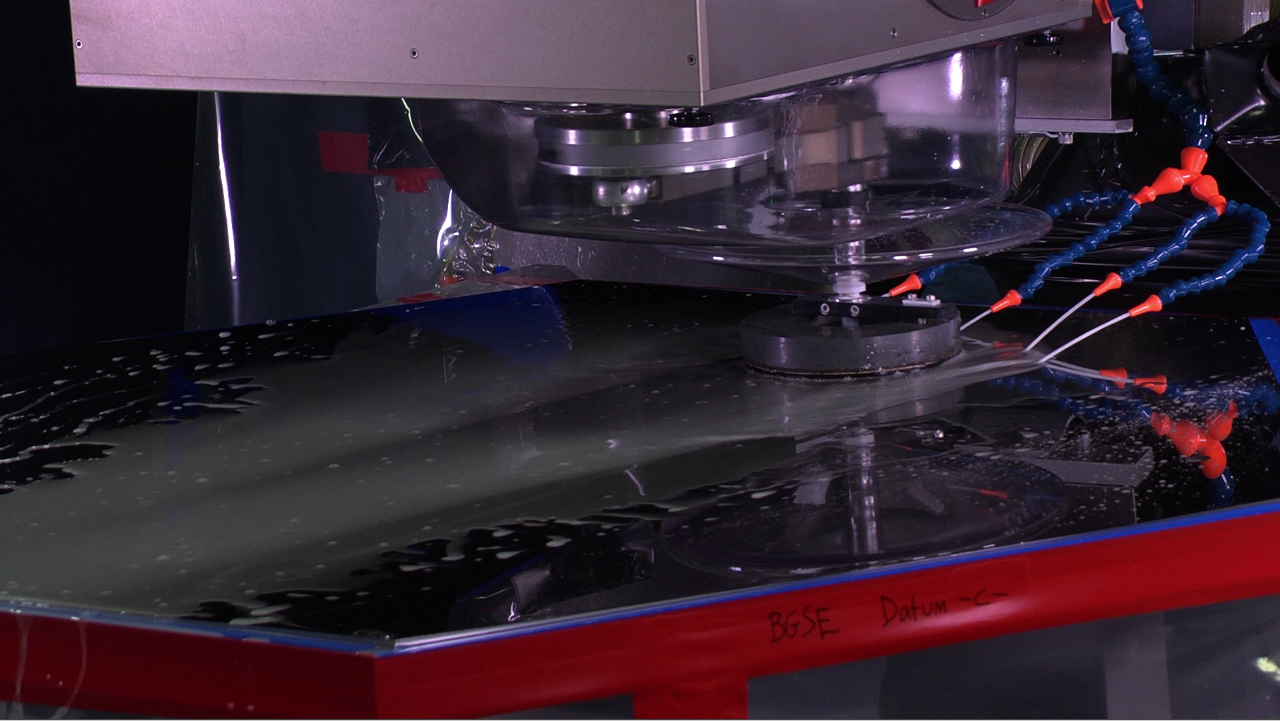

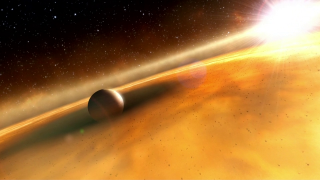

Webb Science Simulations: Planetary Systems and Origins of Life

Go to this pageSupercomputer simulations of planeratry evolution. Part 1: Turbulent Molecular Cloud Nebula with Protostellar ObjectsThe Advanced Visualization Laboratory (AVL) at the National Center for Supercomputing Applications (NCSA) collaborated with NASA and Drs. Alexei Kritsuk and Michael Norman to visualize a computational data set of a turbulent molecular cloud nebula forming protostellar objects and accretion disks approximately 100 AU in diameter, on the order of the size of our solar system. AVL used its Amore software to interpolate and render the Adaptive Mesh Refinement (AMR) simulation generated from ENZO code for cosmology and astrophysics. The AMR simulation was developed by Drs. Kritsuk and Norman at the Laboratory for Computational Astrophysics. The AMR simulation generated more than 2 terabytes of data and follows star formation processes in a self-gravitating turbulent molecular cloud with a dynamic range of half-a-million in linear scale, resolving both the large-scale filamentary structure of the molecular cloud (~5 parsec) and accretion disks around emerging young protostellar objects (down to 2 AU). Part 2: Protoplanetary Disk and Planet FormationThe Advanced Visualization Laboratory (AVL) at the National Center for Supercomputing Applications (NCSA) collaborated with NASA and Dr. Aaron Boley to visualize the 16,000 year evolution of a young, isolated protoplanetary disk which surrounds a newly-formed protostar. The disk forms spiral arms and a dense clump as a result of gravitational collapse. Dr. Aaron Boley developed this computational model to investigate the response of young disks to mass accretion from their surrounding envelopes, including the direct formation of planets and brown dwarfs through gravitational instability. The main formation mechanism for gas giant planets has been debated within the scientific community for over a decade. One of these theories is 'direct formation through gravitational instability.' If the self-gravity of the gas overwhelms the disk's thermal pressure and the stabilizing effect of differential rotation, the gas closest to the protostar rotates faster than gas farther away. In this scenario, regions of the gaseous disk collapse and form a planet directly. The study, presented in Boley (2009), explores whether mass accretion in the outer regions of disks can lead to such disk fragmentation. The simulations show that clumps can form in situ at large disk radii. If the clumps survive, they can become gas giants on wide orbits, e.g., Fomalhaut b, or even more massive objects called brown dwarfs. Whether a disk forms planets at large radii and, if so, the number of planets that form, depend on how much of the envelope mass is distributed at large distances from the protostar. The results of the simulations suggest that there are two modes of gas giant planet formation. The first mode occurs early in the disk's lifetime, at large radii, and through the disk instability mechanism. After the main accretion phase is over, gas giants can form in the inner disk, over a period of a million years, through the core accretion mechanism, which researchers are addressing in other studies.Thanks to R. H. Durisen, L. Mayer, and G. Lake for comments and discussions relating to this research. This study was supported in part by the University of Zurich, Institute for Theoretical Physics, and by a Swiss Federal Grant. Resources supporting this work were provided by the NASA High-End Computing (HEC) Program through the NASA Advanced Supercomputing (NAS) Division at Ames Research Center.AVL at NCSA, University of Illinois. ||

Instrument & Component Animation

Webb Science Instrument Animations

Go to this sectionAnimations of James Webb Space Telescope Instruments

NIRCam Instrument Animation

Go to this sectionThe Near Infrared Camera (NIRCam) is Webb's primary imager that will cover the infrared wavelength range 0.6 to 5 microns. NIRCam will detect light from: the earliest stars and galaxies in the process of formation, the population of stars in nearby galaxies, as well as young stars in the Milky Way and Kuiper Belt objects. NIRCam is equipped with coronagraphs, instruments that allow astronomers to take pictures of very faint objects around a central bright object, like stellar systems. NIRCam's coronagraphs work by blocking a brighter object's light, making it possible to view the dimmer object nearby - just like shielding the sun from your eyes with an upraised hand can allow you to focus on the view in front of you. With the coronagraphs, astronomers hope to determine the characteristics of planets orbiting nearby stars.

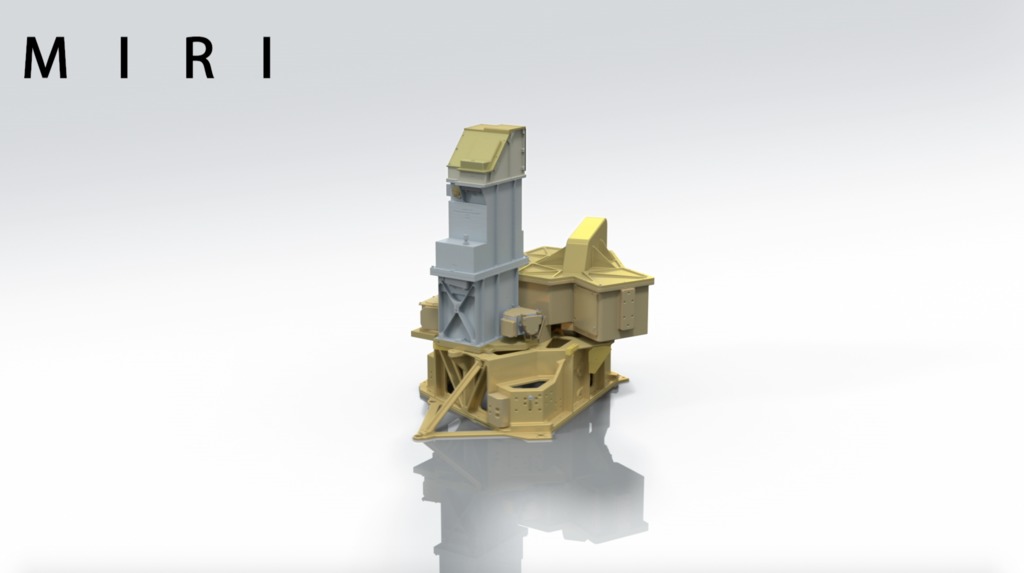

Webb's Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI) Light Path Animation

Go to this pageThe spectrograph light path inside the Mid Infrared Instrument (MIRI) on the Webb Telescope. Versions with labels and without labels.Credit: European Space Agency || MIRI_SPECTRO_v2.00030_print.jpg (1024x576) [40.5 KB] || MIRI_SPECTRO_v2.00030_searchweb.png (320x180) [21.1 KB] || MIRI_SPECTRO_v2.00030_web.png (320x180) [21.1 KB] || MIRI_SPECTRO_v2.00030_thm.png (80x40) [2.1 KB] || MIRI_SPECTRO_v2.mp4 (1920x1080) [156.3 MB] || MIRI_SPECTRO_labels_v3.mp4 (1920x1080) [177.9 MB] || MIRI_SPECTRO_v2.webm (1920x1080) [9.0 MB] ||

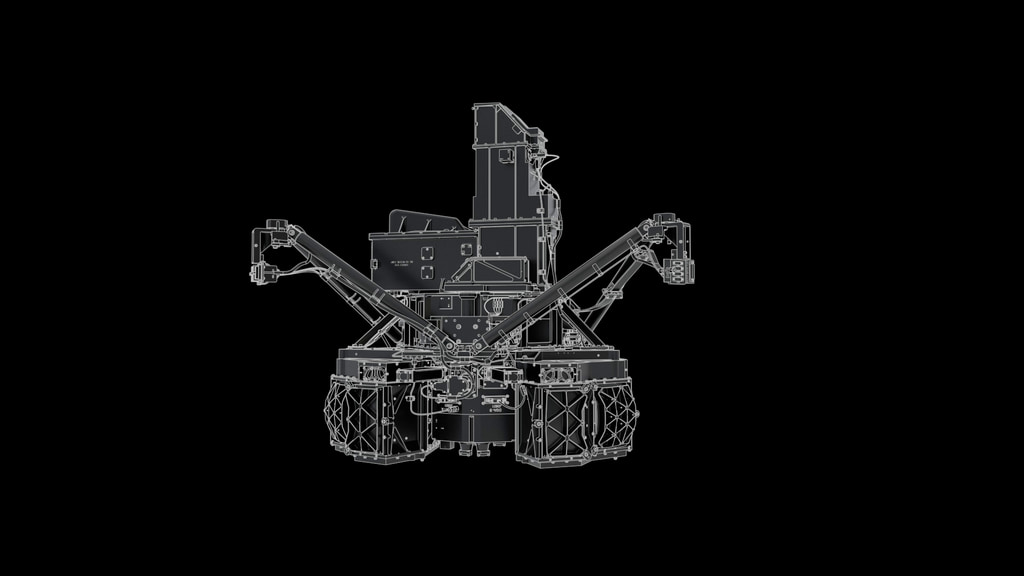

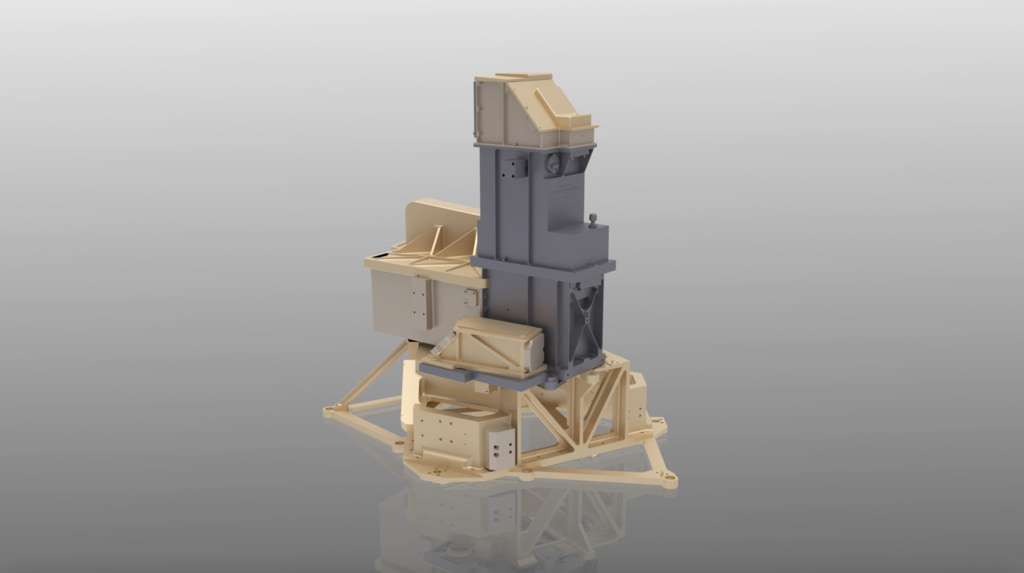

MIRI Instrument Turntable Animation

Go to this pageA turntable animation of Webb's Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI). || Miri_Screen_Shot_2021_print.jpg (1024x573) [42.3 KB] || Miri_Screen_Shot_2021.png (3338x1870) [1.4 MB] || Miri_Screen_Shot_2021_searchweb.png (320x180) [26.4 KB] || Miri_Screen_Shot_2021_thm.png (80x40) [5.9 KB] || MiriTT.mp4 (1280x720) [6.2 MB] || MiriTT4k.mov (3840x2160) [268.8 MB] || MiriTTh2644K.mp4 (3840x2160) [20.3 MB] || MiriTT4k.webm (3840x2160) [1.7 MB] ||

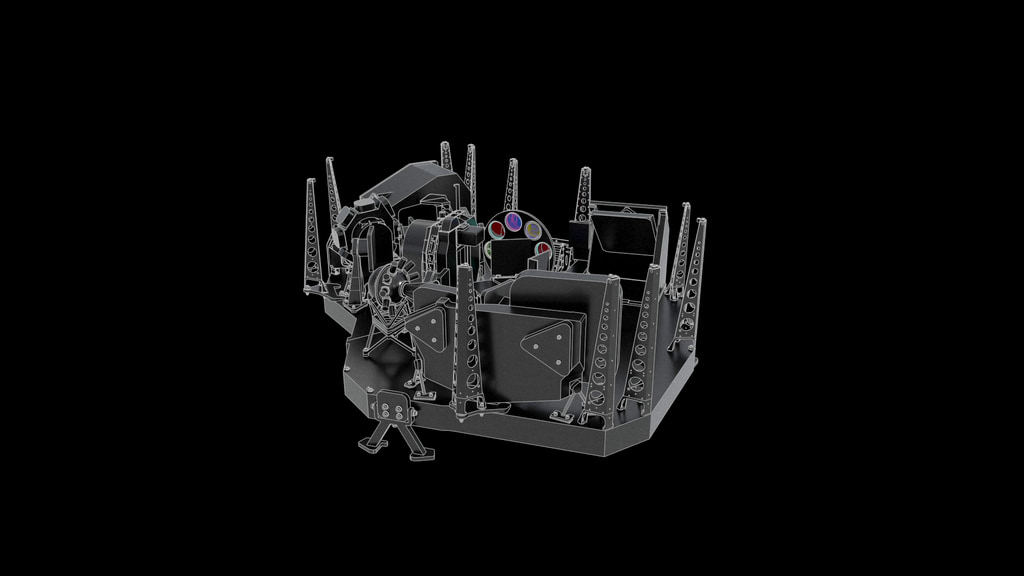

Webb's Near Infrared Spectrograph (NIRSpec) Instrument Light Path Animation

Go to this pageAnimation of the light path inside the Near Infrared Spectrometer (NIRSpec) on the Webb Telescope. Showing simulated data.Credit: European Space Agency || NIRSPEC_IFU_with_graph_v3.00030_print.jpg (1024x576) [39.9 KB] || NIRSPEC_IFU_with_graph_v3.00030_searchweb.png (320x180) [19.7 KB] || NIRSPEC_IFU_with_graph_v3.00030_web.png (320x180) [19.7 KB] || NIRSPEC_IFU_with_graph_v3.00030_thm.png (80x40) [2.1 KB] || NIRSPEC_IFU_with_graph_v3.mp4 (1920x1080) [311.7 MB] || NIRSPEC_IFU_with_graph_v3.webm (1920x1080) [12.7 MB] ||

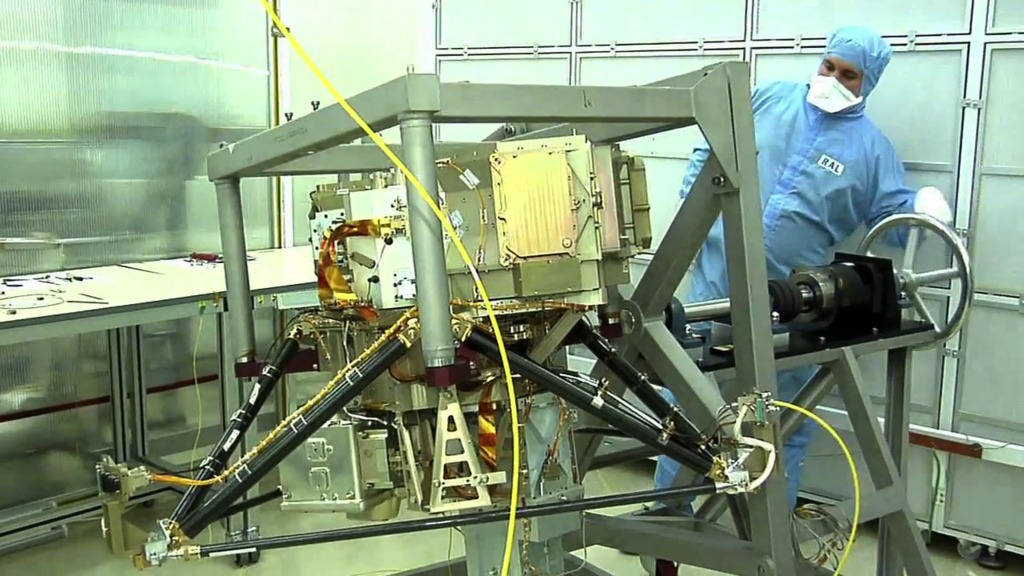

NIRSpec Instrument Animation

Go to this sectionThe Near InfraRed Spectrograph (NIRSpec) will operate over a wavelength range of 0.6 to 5 microns. A spectrograph (also sometimes called a spectrometer) is used to disperse light from an object into a spectrum. Analyzing the spectrum of an object can tell us about its physical properties, including temperature, mass, and chemical composition. The atoms and molecules in the object actually imprint lines on its spectrum that uniquely fingerprint each chemical element present and can reveal a wealth of information about physical conditions in the object. Spectroscopy and spectrometry (the sciences of interpreting these lines) are among the sharpest tools in the shed for exploring the cosmos. Many of the objects that the Webb will study, such as the first galaxies to form after the Big Bang, are so faint, that the Webb's giant mirror must stare at them for hundreds of hours in order to collect enough light to form a spectrum. In order to study thousands of galaxies during its 5 year mission, the NIRSpec is designed to observe 100 objects simultaneously. The NIRSpec will be the first spectrograph in space that has this remarkable multi-object capability. To make it possible, Goddard scientists and engineers had to invent a new technology microshutter system to control how light enters the NIRSpec.

FGS/NIRISS Turntable Animation

Go to this sectionThe Fine Guidance Sensor (FGS) allows Webb to point precisely, so that it can obtain high-quality images. The Near Infrared Imager and Slitless Spectrograph part of the FGS/NIRISS will be used to investigate the following science objectives: first light detection, exoplanet detection and characterization, and exoplanet transit spectroscopy.

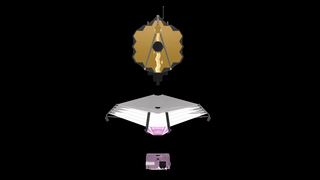

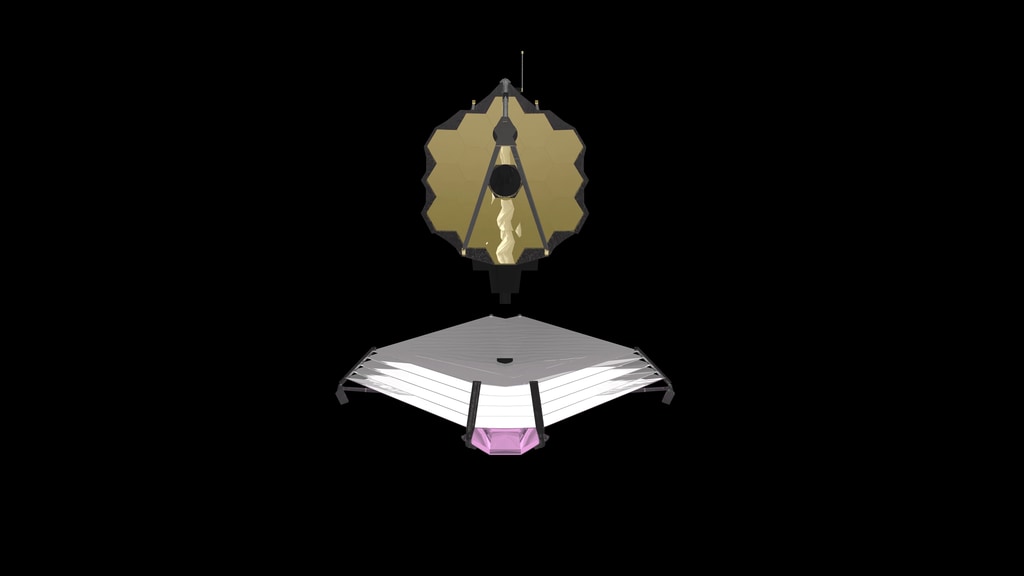

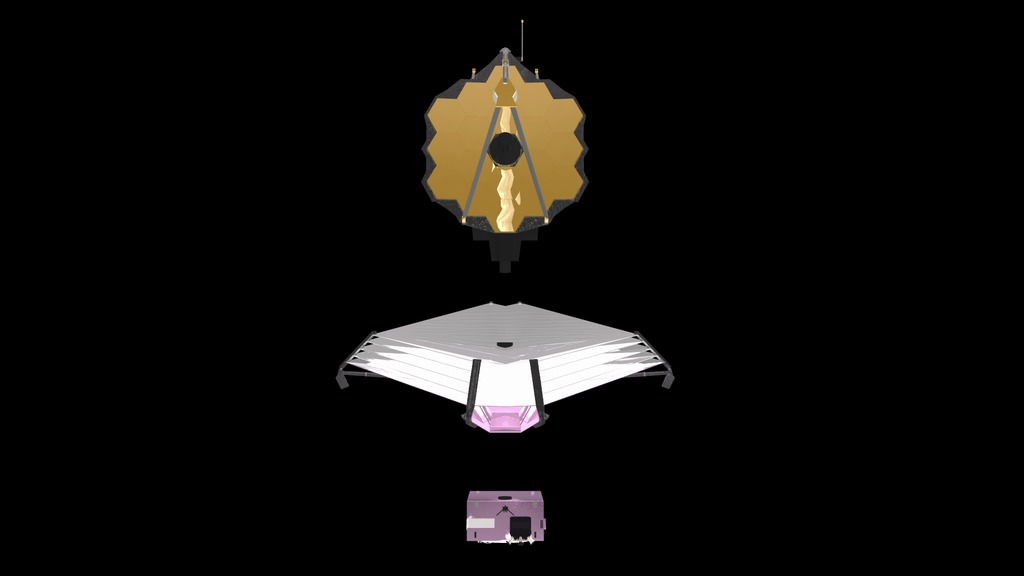

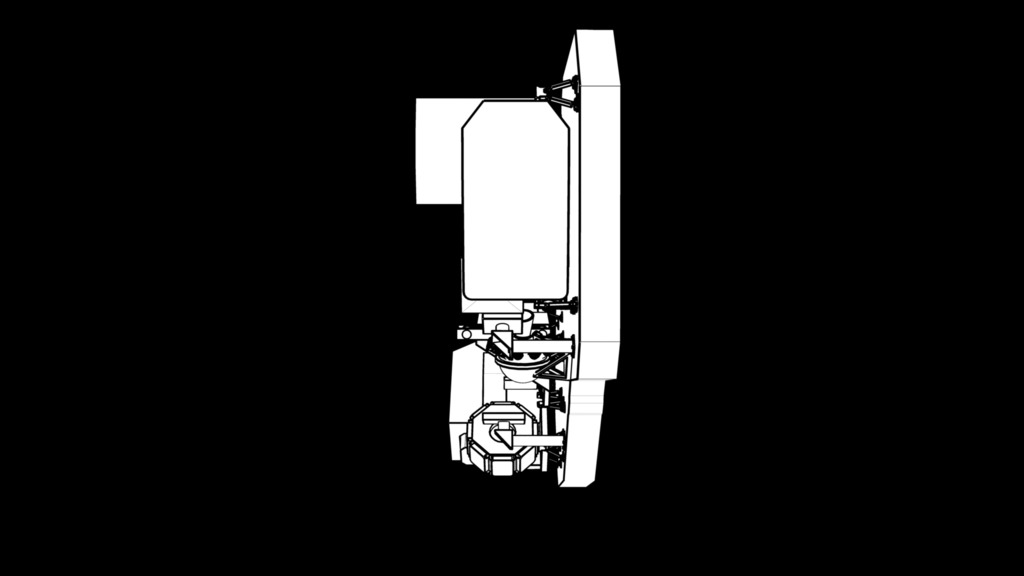

Webb Spacecraft 2-Segment Animation with Instrument view

Go to this sectionAnimation shows the two main sections of the Webb Telescope: the Optical Telescope Integrated Science (OTIS) segment and the Spacecraft Element (SCE) segment. The animation also reveals the location of Webb's four instruments.

Webb Spacecraft Segment Animation (with alpha)

Go to this pageAnimation (with alpha channel) of the three main segments of the James Webb Space Telescope with quick in and out to show cutaway for Webb's instruments. || JWST-3-segment-in-out.00294_print.jpg (1024x576) [25.3 KB] || JWST-3-segment-in-out.00294_searchweb.png (180x320) [12.7 KB] || JWST-3-segment-in-out.00294_web.png (320x180) [12.7 KB] || JWST-3-segment-in-out.00294_thm.png (80x40) [1.8 KB] || JWST-3-segment-in-out.webm (1920x1080) [3.5 MB] || JWST_BG.png (8192x4096) [128.0 MB] || JWST-3-segment-in-out.mov (1920x1080) [341.6 MB] ||

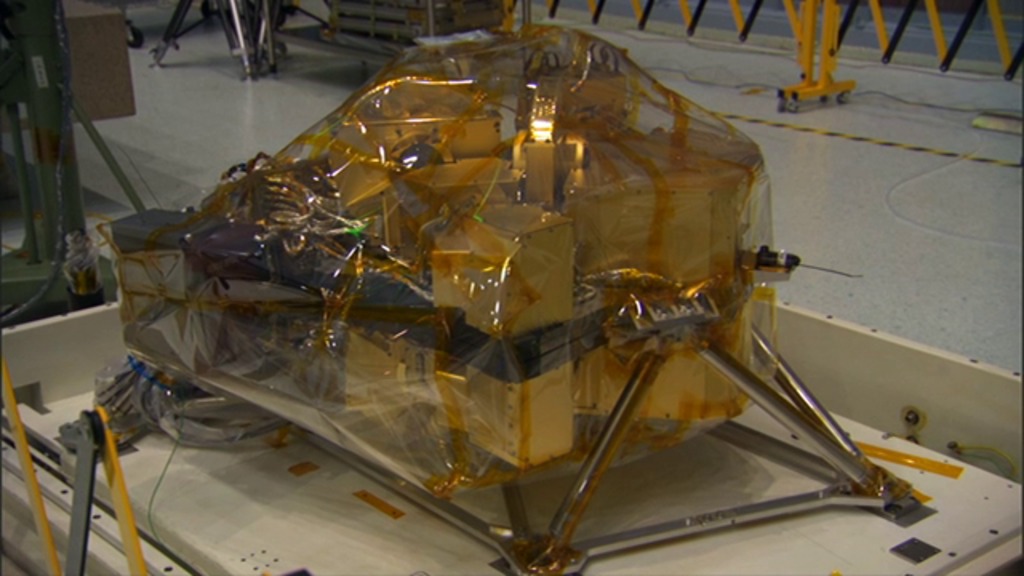

Webb Telescope Instrument Animations

Go to this pageThe James Webb Space Telelscope carries 4 science instruments: the Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI), the Near-Infrared Camera (NIRCam), the Near-Infrared Spectrograph (NIRSpec), and the Fine Guidance Sensor / Near InfraRed Imager adn Slitless Spetrograph (FGS/NIRISS). All four instruments are housed in the Integrated Science Instrument Module (ISIM). ||

Descriptive Concept Animations

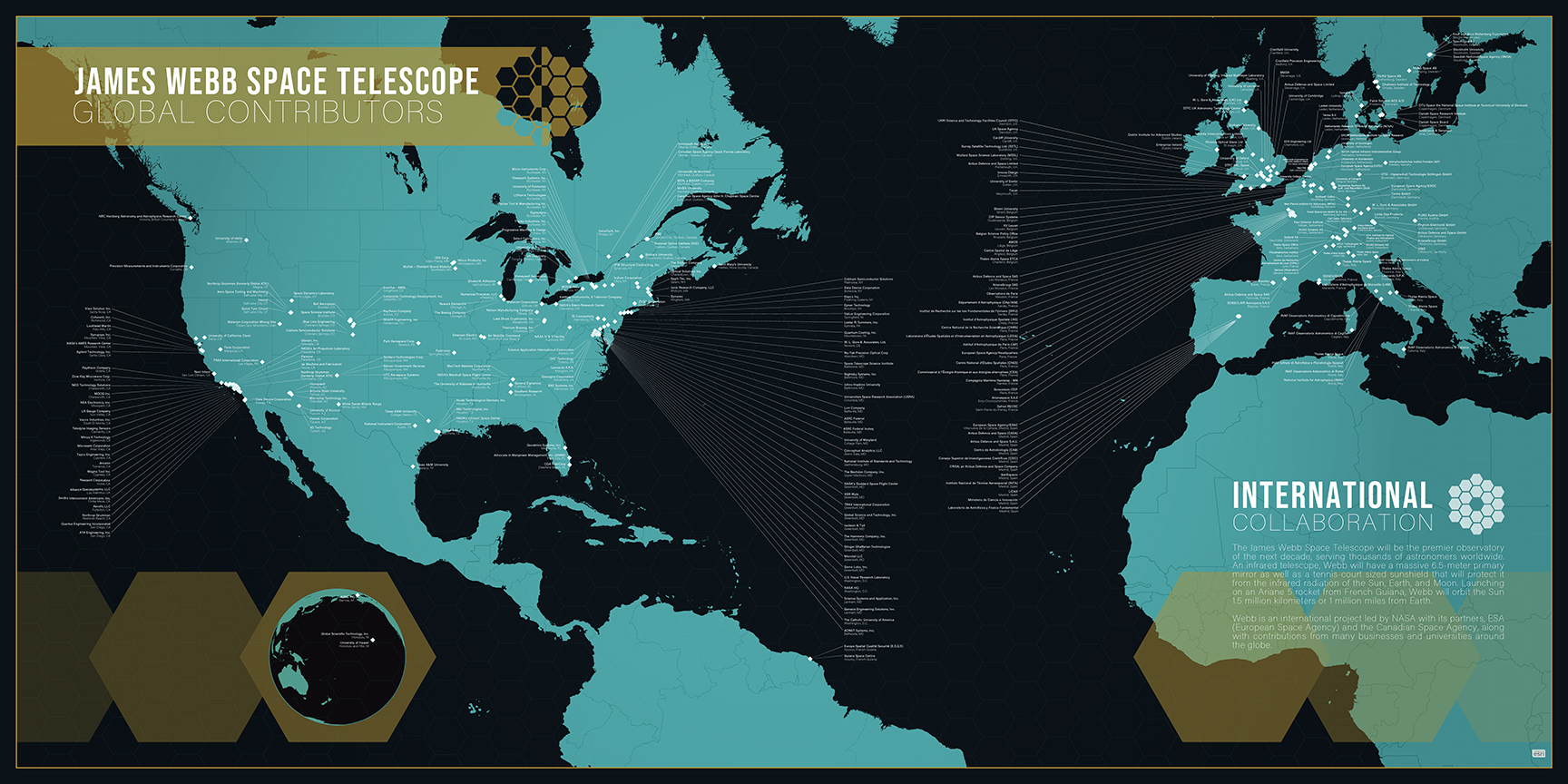

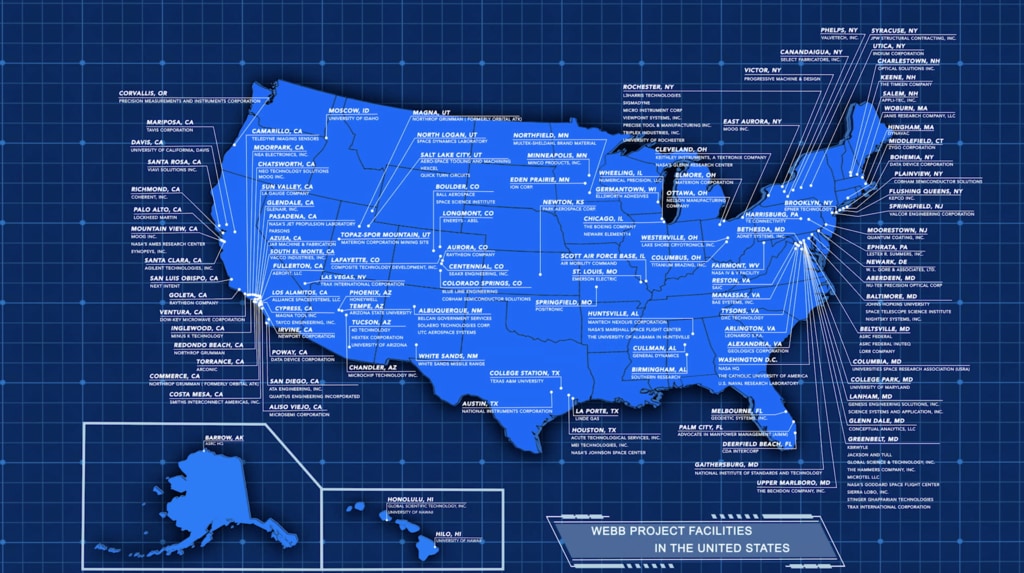

Webb Global Contributor Map

Go to this pageFlyover animation of map of Webb Global Contributors || A_JWST_Contributor_Map_0420_72dpi_2.jpg (3456x1728) [922.7 KB] || A_JWST_Contributor_Map_0420_72dpi_2_thm.png (80x40) [6.2 KB] || A_JWST_Contributor_Map_0420_72dpi_2_searchweb.png (320x180) [77.9 KB] || A_JWST_Contributor_Map_0420_Animated.mov (5120x2160) [4.2 GB] || A_JWST_Contributor_Map_0420_Animated.mp4 (5120x2160) [40.9 MB] || A_JWST_Contributor_Map_0420_Animated.webm (5120x2160) [10.5 MB] ||

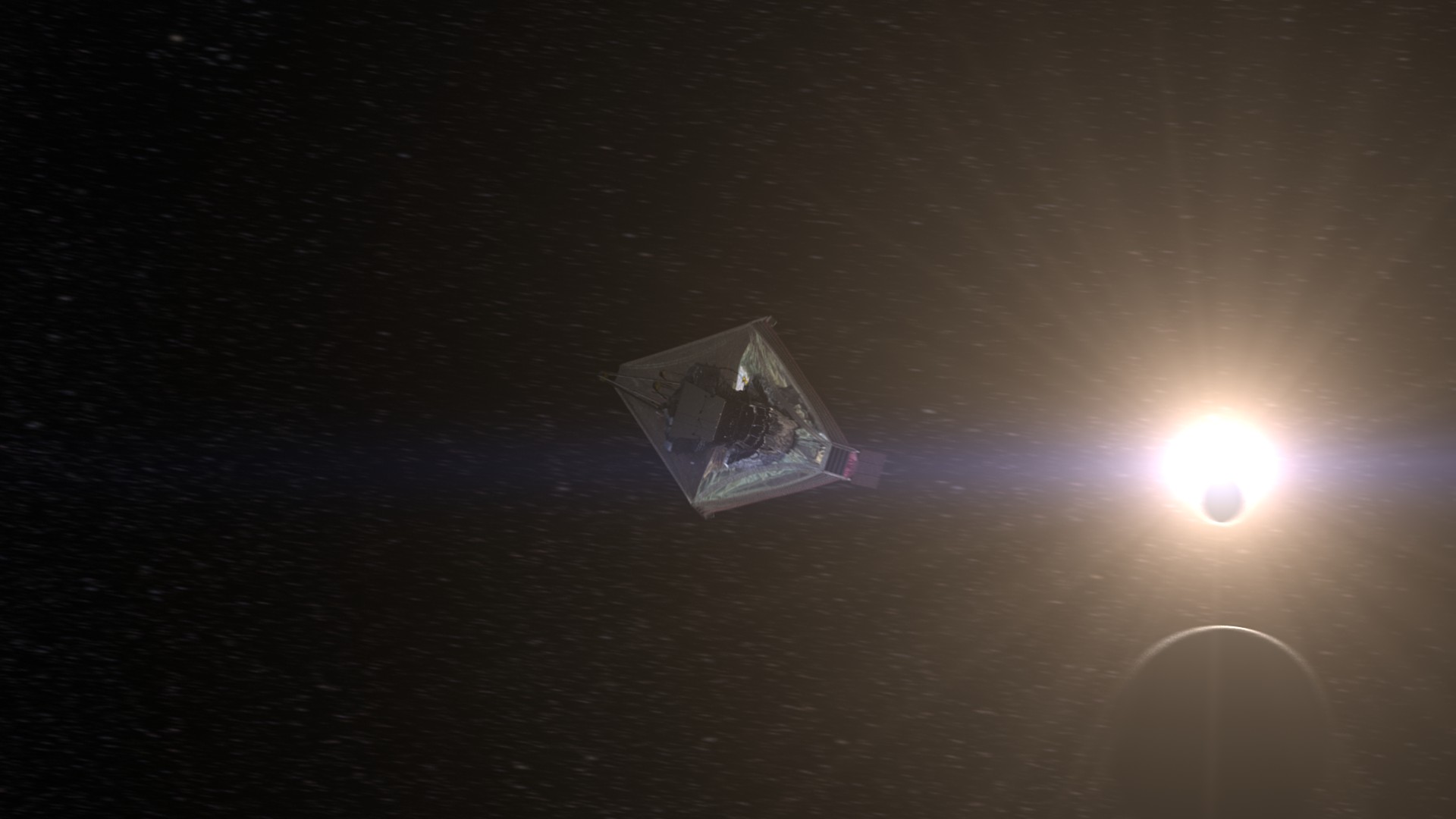

James Webb Space Telescope Launch and Orbit at L2

Go to this sectionThe James Webb Space Telescope (sometimes called JWST) is a large, infrared-optimized space telescope. The observatory launched into space on an Ariane 5 rocket from the Guiana Space Centre in Kourou, French Guiana on December 25, 2021. After launch, the observatory was successfully unfolded and is being readied for science. Webb will find the first galaxies that formed in the early Universe, connecting the Big Bang to our own Milky Way Galaxy. Webb will peer through dusty clouds to see stars forming planetary systems, connecting the Milky Way to our own Solar System. The James Webb Space Telescope will not be in orbit around the Earth, like the Hubble Space Telescope is - it will actually orbit the Sun, 1.5 million kilometers (1 million miles) away from the Earth at what is called the second Lagrange point or L2. What is special about this orbit is that it lets the telescope stay in line with the Earth as it moves around the Sun. This allows the satellite's large sunshield to protect the telescope from the light and heat of the Sun and Earth (and Moon).

James Webb Space Telescope Orbit

Go to this sectionThe James Webb Space Telescope will not be in orbit around the Earth, like the Hubble Space Telescope is - it will actually orbit the Sun, 1.5 million kilometers (1 million miles) away from the Earth at what is called the second Lagrange point or L2. What is special about this orbit is that it lets the telescope stay in line with the Earth as it moves around the Sun. This allows the satellite's large sunshield to protect the telescope from the light and heat of the Sun and Earth (and Moon).

Folding the Webb Telescope to Fit Inside Ariane 5 Rockete Fairing

Go to this sectionAnimation showing the Webb Space Telescope folding to fit inside the Ariane 5 rocket fairing.

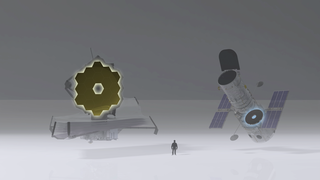

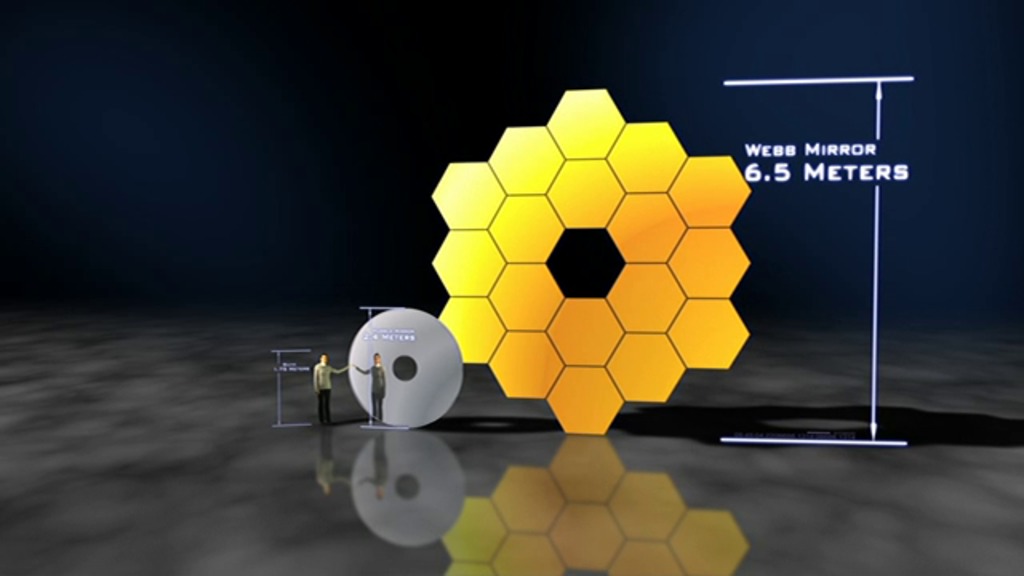

Primary Mirror Size Comparison Between Webb and Hubble

Go to this pageWebb Telescope and Hubble Telescope primary mirror comparison with person as reference. || JWST_2020_composite_mirror_with_Person.00028_print.jpg (1024x576) [29.9 KB] || JWST_2020_composite_mirror_with_Person.00028_searchweb.png (180x320) [38.2 KB] || JWST_2020_composite_mirror_with_Person.00028_web.png (320x180) [38.2 KB] || JWST_2020_composite_mirror_with_Person.00028_thm.png (80x40) [3.9 KB] || JWST_2020_composite_mirror_with_Person.mov (3840x2160) [866.1 MB] || JWST_2020_composite_mirror_with_Person.webm (3840x2160) [3.0 MB] || JWST_2020_composite_mirror_with_Person.mp4 (3840x2160) [9.6 MB] ||

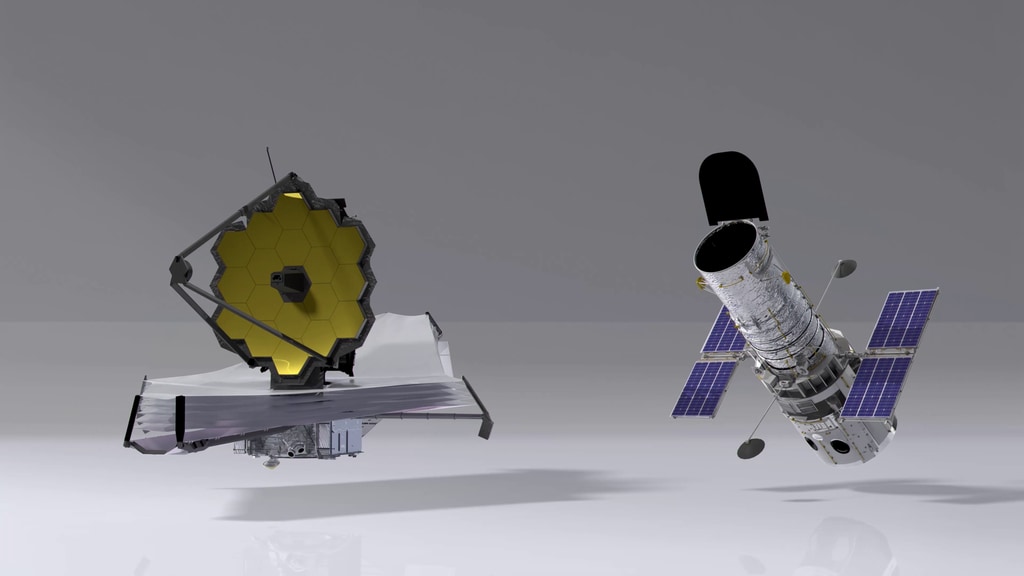

Spacecraft Size Comparison Between the Webb Space Telescope and the Hubble Space Telescope

Go to this pageSize comparison between the Webb Space Telescope and the Hubble Space Telescope. || JWST_v_HST_TTable_4k_woPerson.00029_print.jpg (1024x576) [44.4 KB] || JWST_v_HST_TTable_4k_woPerson.00029_searchweb.png (320x180) [35.8 KB] || JWST_v_HST_TTable_4k_woPerson.00029_thm.png (80x40) [3.9 KB] || JWST_v_HST_TTable_4k_woPerson.mov (3840x2160) [1.8 GB] || JWST_v_HST_TTable_4k_woPerson.mp4 (3840x2160) [11.5 MB] || JWST_v_HST_TTable_4k_woPerson.webm (3840x2160) [4.1 MB] ||

Webb Mirror Size Comparison with Hubble Animation

Go to this pageAnimation comparing the relative sizes of James Webb's primary mirror to Hubble's primary mirror. ||

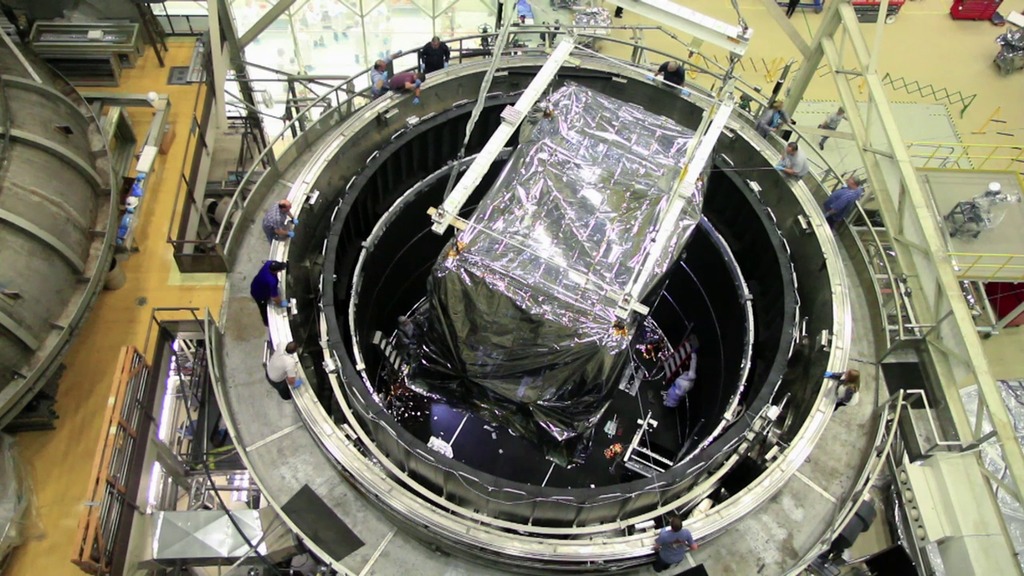

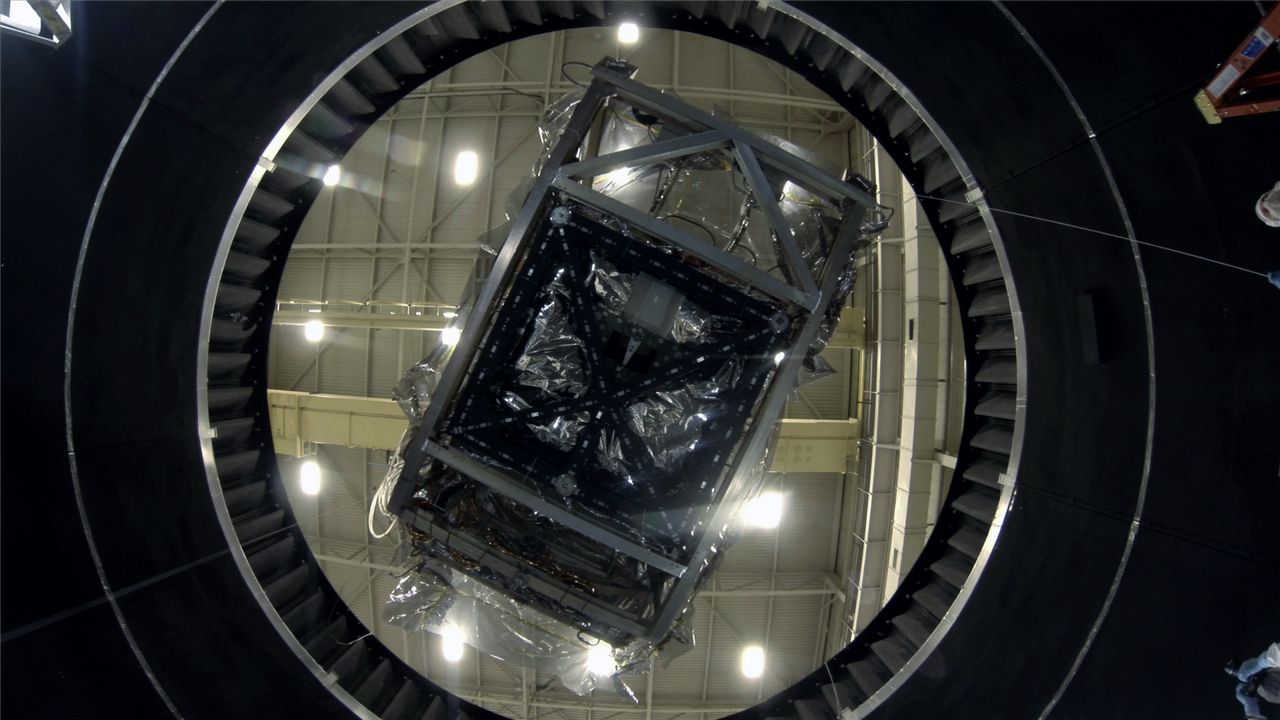

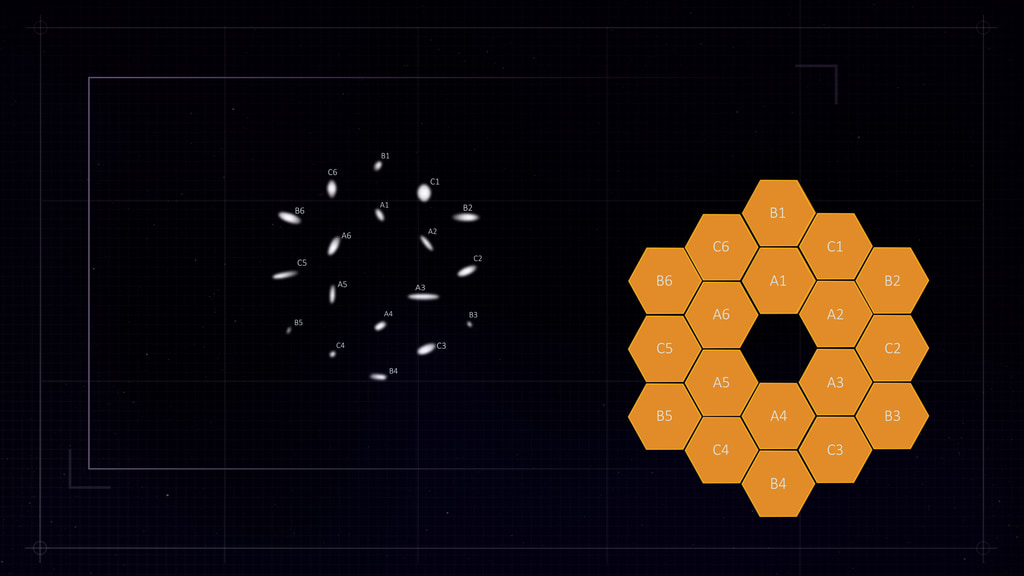

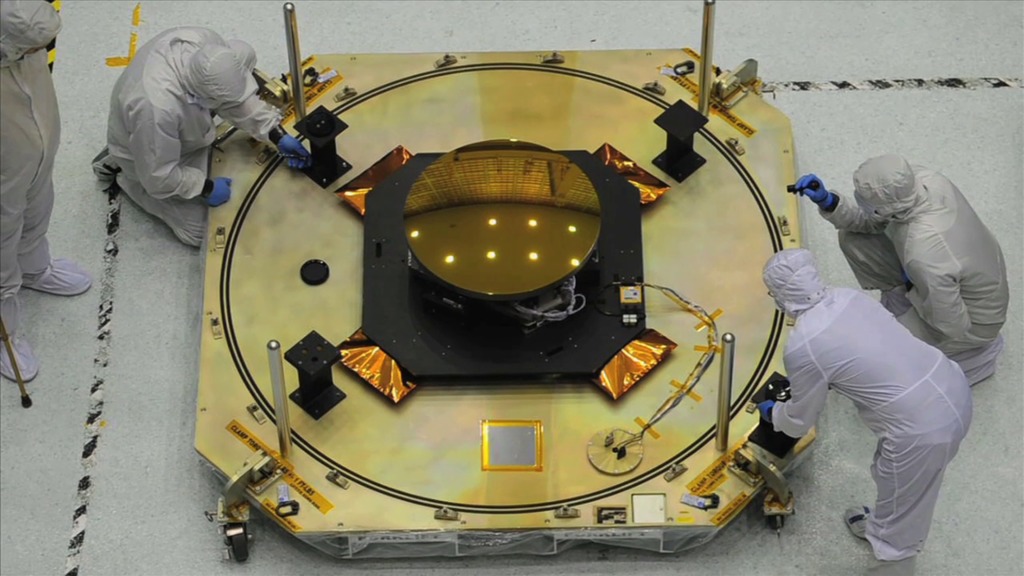

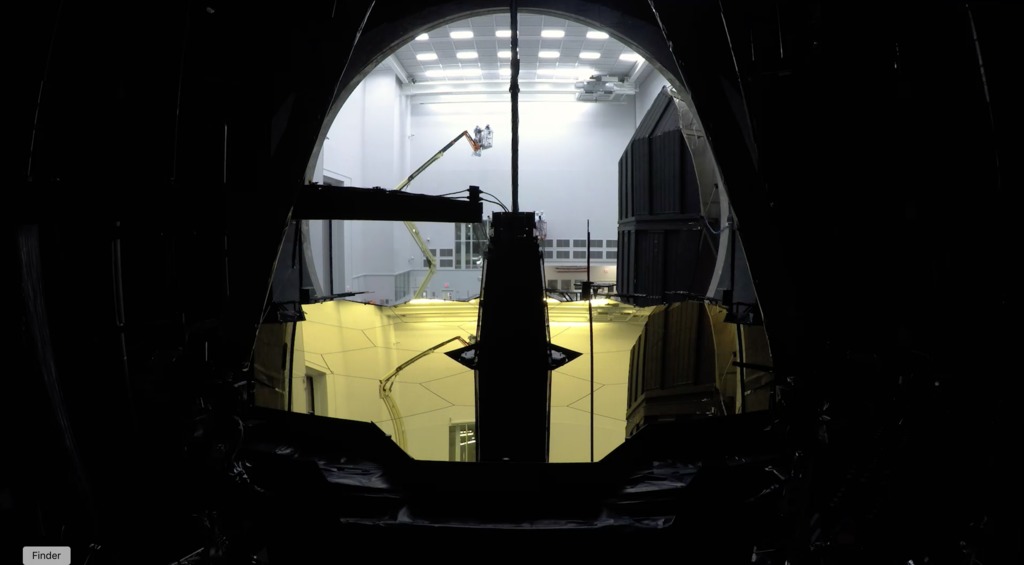

Alignment of the Primary Mirror Segments of The James Webb Space Telescope

Go to this pageAnimation of the James Webb Space Telescope mirror alignment and phasing process. || 1-Webb_Mirror_Phasing_in_Chamber_A_Social_media0.jpg (1920x1080) [772.4 KB] || 1-Webb_Mirror_Phasing_in_Chamber_A_Social_media0_searchweb.png (320x180) [62.3 KB] || 1-Webb_Mirror_Phasing_in_Chamber_A_Social_media0_thm.png (80x40) [5.3 KB] || JWST_MirrorPhasing_animation_ProRes.mov (1920x1080) [4.2 GB] || JWST_MirrorPh.mp4 (1920x1080) [110.4 MB] || JWST_MirrorPhasing_animation_ProRes.webm (1920x1080) [8.1 MB] ||

Webb Orbit

Go to this pageAn animation showing the relative location of the Webb Telelscope related to the Earth, Moon and Sun. ||

Webb Journey To Space Series

Webb Journey to Space 1: Packing & Transport

Go to this pageThis is the beginning of the James Webb Space Telescope's journey to space! It started with engineers packing the telescope into the protective transport container. The container was then moved from Northrop Grumman in Redondo Beach, CA to Seal Beach, CA. Waiting at Seal Beach was the ship, the MN Colibri, which would carry Webb to the port near the launch site in French Guiana. ||

Webb Journey to Space 2: Loading & Departure

Go to this pageThe Webb Telescope's journey to space continues... After arriving at Seal Beach, California, Webb, inside of the protective transport container, was loaded into the MN Colibri. This process took several steps to accomplish. Once the telescope was loaded inside the cargo hold, the MN Colibri set sail for the port near the launch site in Kourou, French Guiana. ||

Webb Journey to Space Part 3 Arrival & Off loaded

Go to this pageThe MN Colibri with the Webb Telescope safely inside the cargo hold has arrived at Kourou in French Guiana, the location of the launch site for Webb. The journey from Los Angeles to Kourou took a total of 16 days. Once the MN Colibri made port, the team of engineers unload Webb still inside the protective transport container from the ship and moved it to Guiana Space Centre. ||

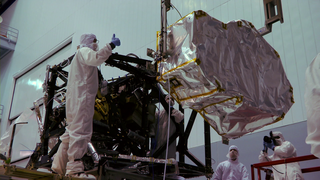

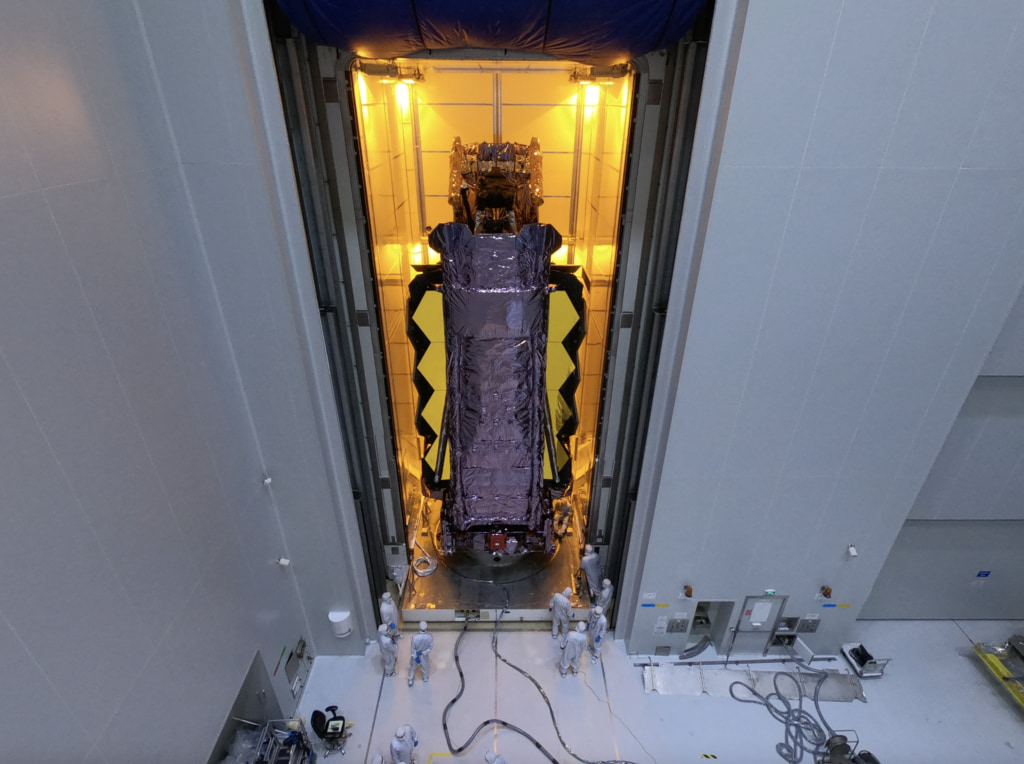

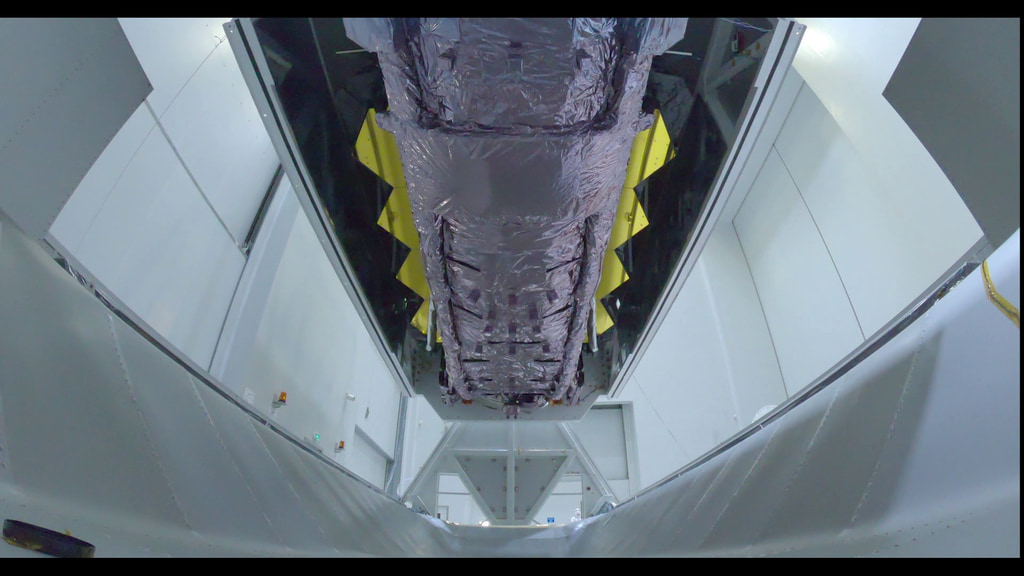

Webb Journey to Space Part 4: Unpacking in the Cleanroom

Go to this pageAfter making its journey to Kourou, French Guiana, the Webb Telescope inside the protective transport container has been brought to the Guiana Space Centre. Once inside the processing facility's cleanroom, engineers unpacked Webb from the protective transport container and installed it to the rollover fixture. The telescope now waits to begin launch preparations. ||

Webb Journey to Space EP5: Spacecraft Fueling

Go to this pageWebb Journey to Space EP5: Spacecraft Fueling || Webb_Journey_To_Space_5_Cover_Image_2_print.jpg (1024x574) [401.7 KB] || Webb_Journey_To_Space_5_Cover_Image_2.jpg (3342x1874) [2.3 MB] || Webb_Journey_To_Space_5_Cover_Image_2_searchweb.png (320x180) [90.5 KB] || Webb_Journey_To_Space_5_Cover_Image_2_thm.png (80x40) [6.5 KB] || Webbs_Journey_to_Space_-Moving_to_S5B.mov (1920x1080) [1.4 GB] || Webbs_Journey_to_Space-Moving_to_S5B_graphics.mov (1920x1080) [1.4 GB] || Webbs_Journey_to_Space-Moving_to_S5B_Graphics.mp4 (1920x1080) [102.1 MB] || Webbs_Journey_to_Space-Moving_to_S5B_no_Graphics.mp4 (1920x1080) [102.1 MB] || Webbs_Journey_to_Space-Moving_to_S5B_Graphics.webm (1920x1080) [11.1 MB] || Webb_Journey_to_Space-Moving_On_to_Fueling.en_US.srt [1.5 KB] || Webb_Journey_to_Space-_Moving_On_to_Fueling.en_US.vtt [1.5 KB] ||

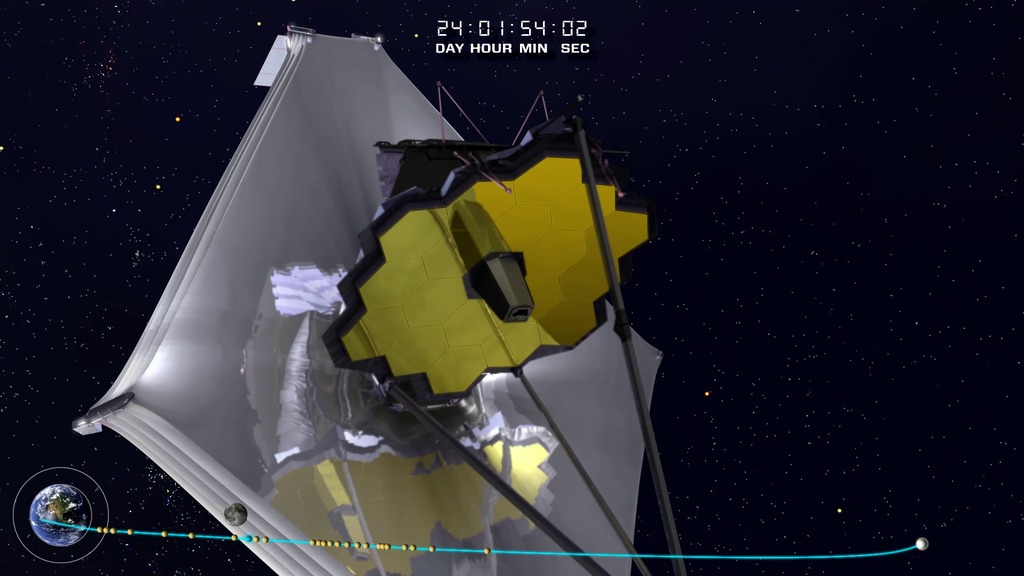

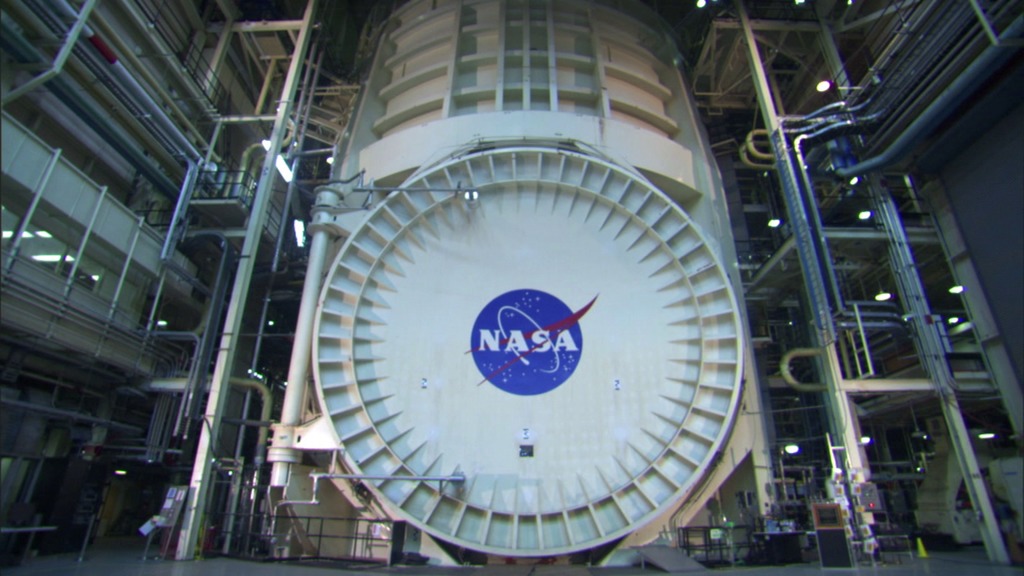

Webb Journey to Space EP6: Launch

Go to this pageThe final chapter of the Webb journey to space. After months of transporting and preparing, the time has finally come. The Webb Telescope first is moved into the Ariane 5 rocket faring at the Guiana Space Centre in Kourou, French Guiana. The rocket with Webb now inside of it, is then moved to the launch pad. On Christmas morning, the rocket is launched into space. Approximately 30 minutes after the rocket made it into space, Webb was seperate for the rocket and slowly started its journey to L2. ||

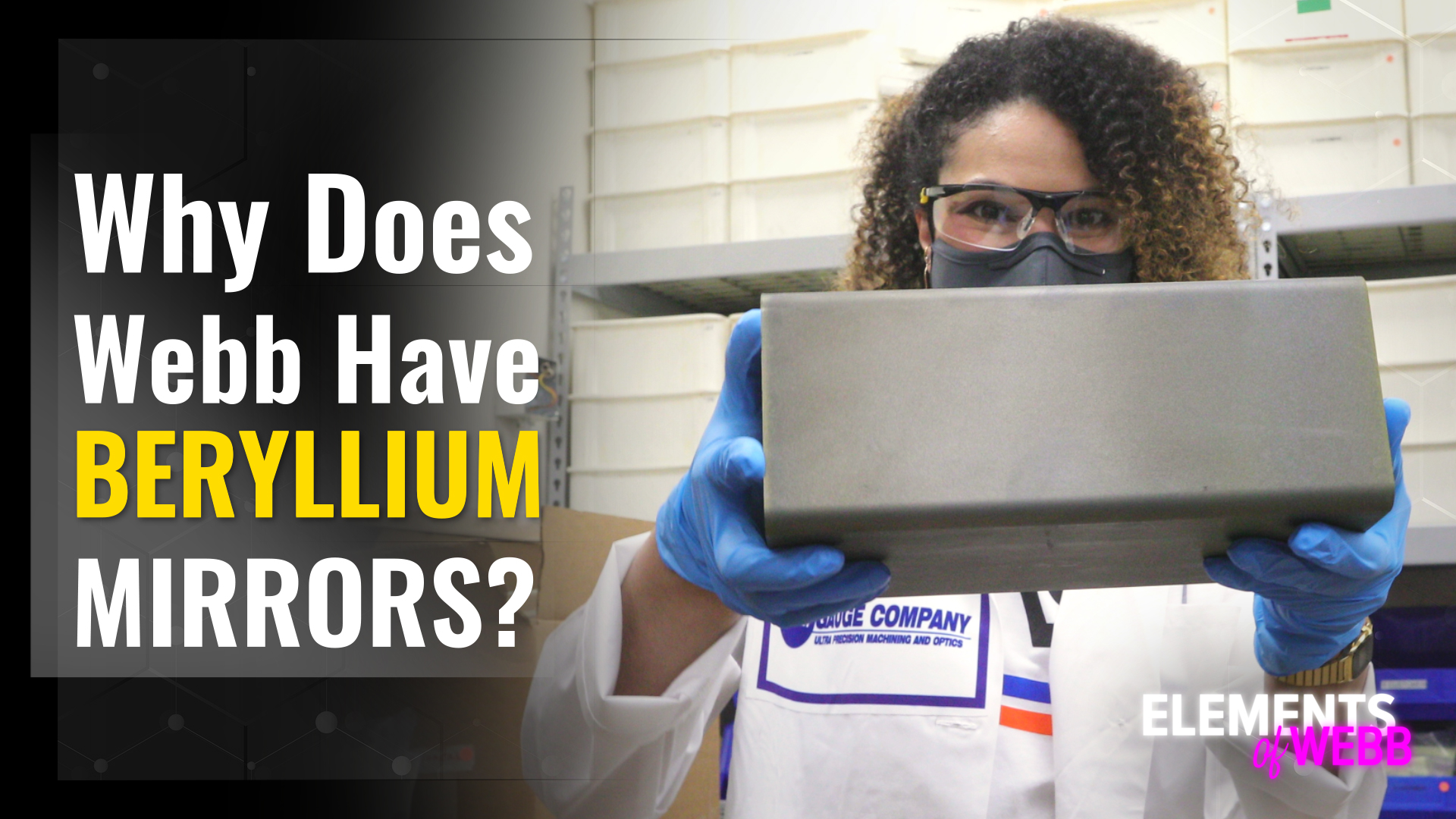

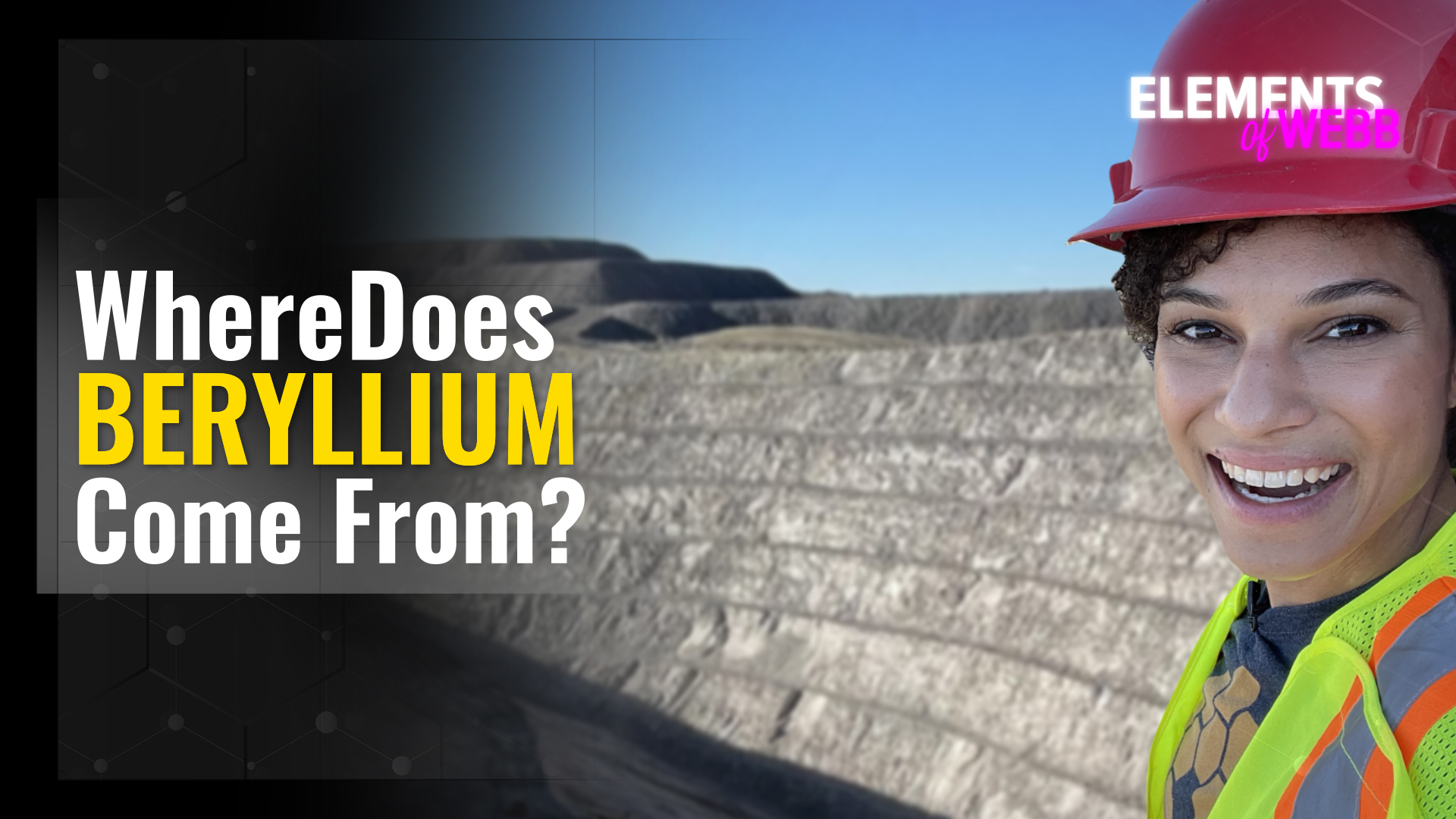

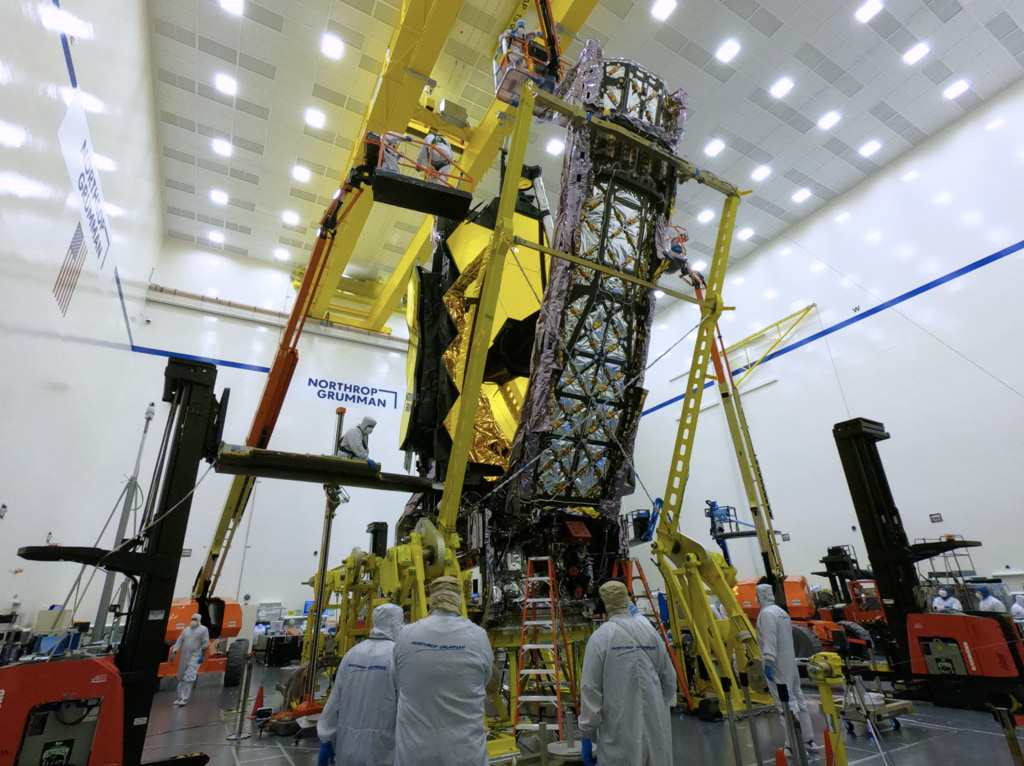

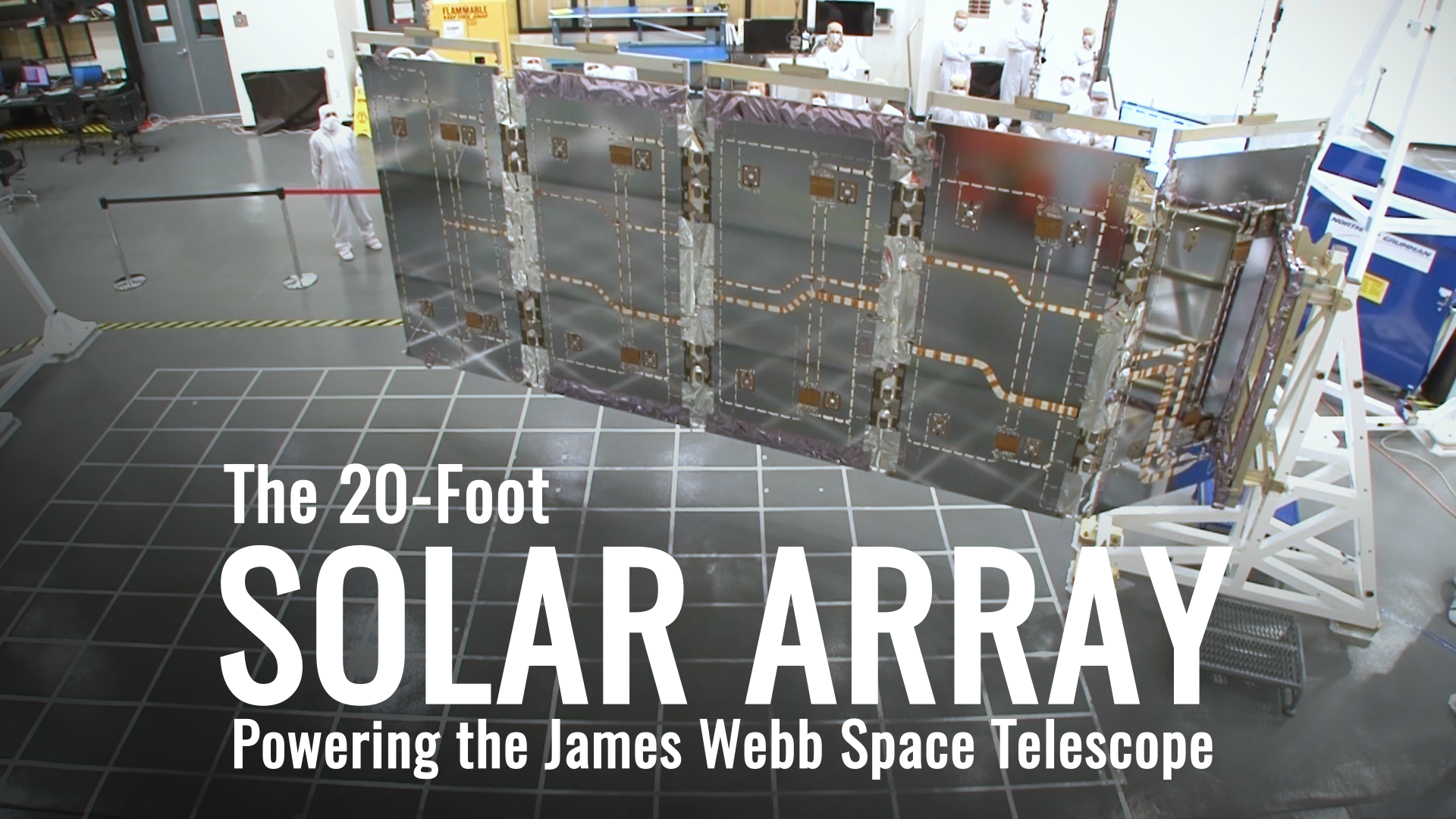

Elements of Webb Series

Elements of Webb explores why engineers chose to use different materials on the James Webb Space Telescope. While Webb towers three stories tall, and has a tennis court sized sunshield and is twice the size of the Hubble Space Telescope, Webb is half Hubble’s weight. Why? Engineers precisely chose the right materials. #UnfoldTheUniverse

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

Webb at the Launch Site

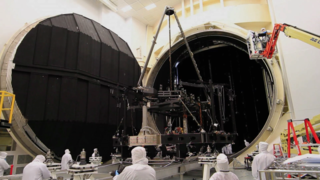

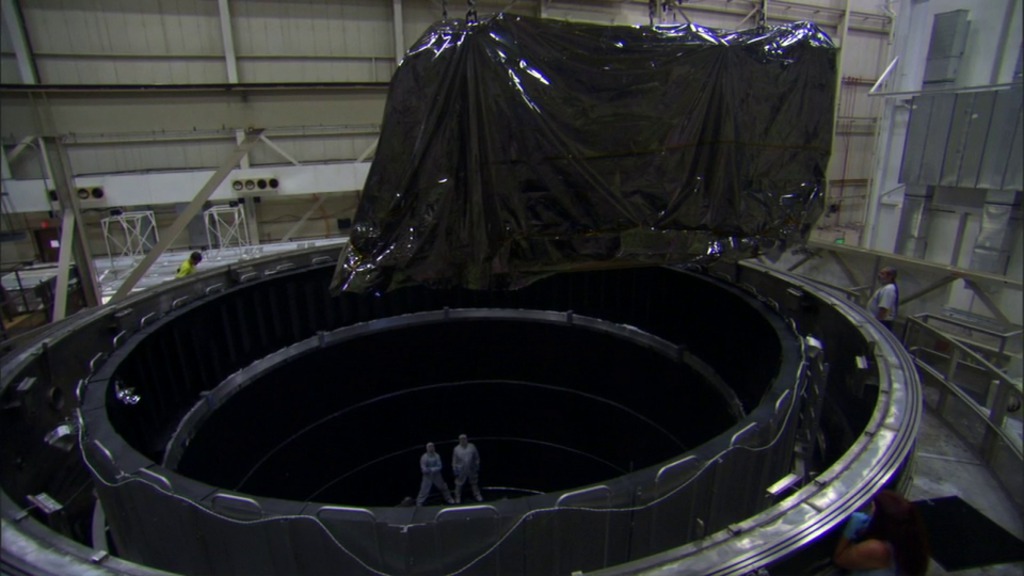

James Webb Space Telescope Encapsulation

Go to this pageEncapsulation marks the final readiness for Webb's flight to space. Here the rocket fairing, or nose cone, of the Ariane 5 rocket was lifted 15 stories and carefully placed over the Webb Telescope. ||

The Webb Telescope Moved for Fueling in French Guiana B-Roll

Go to this pageB-roll footage of engineers moving the Webb Telescope from the S5C building to S5B building to begin fueling the telescope at the Guiana Space Centre in Kourou, French Guiana. ||

The Webb Telescope Installed to the Payload Adapter Ring In French Guiana B-Roll

Go to this pageB-roll footage of engineers installing the Webb Telescope to the payload adapter ring at Guiana Space Centre in Kourou, French Guiana. ||

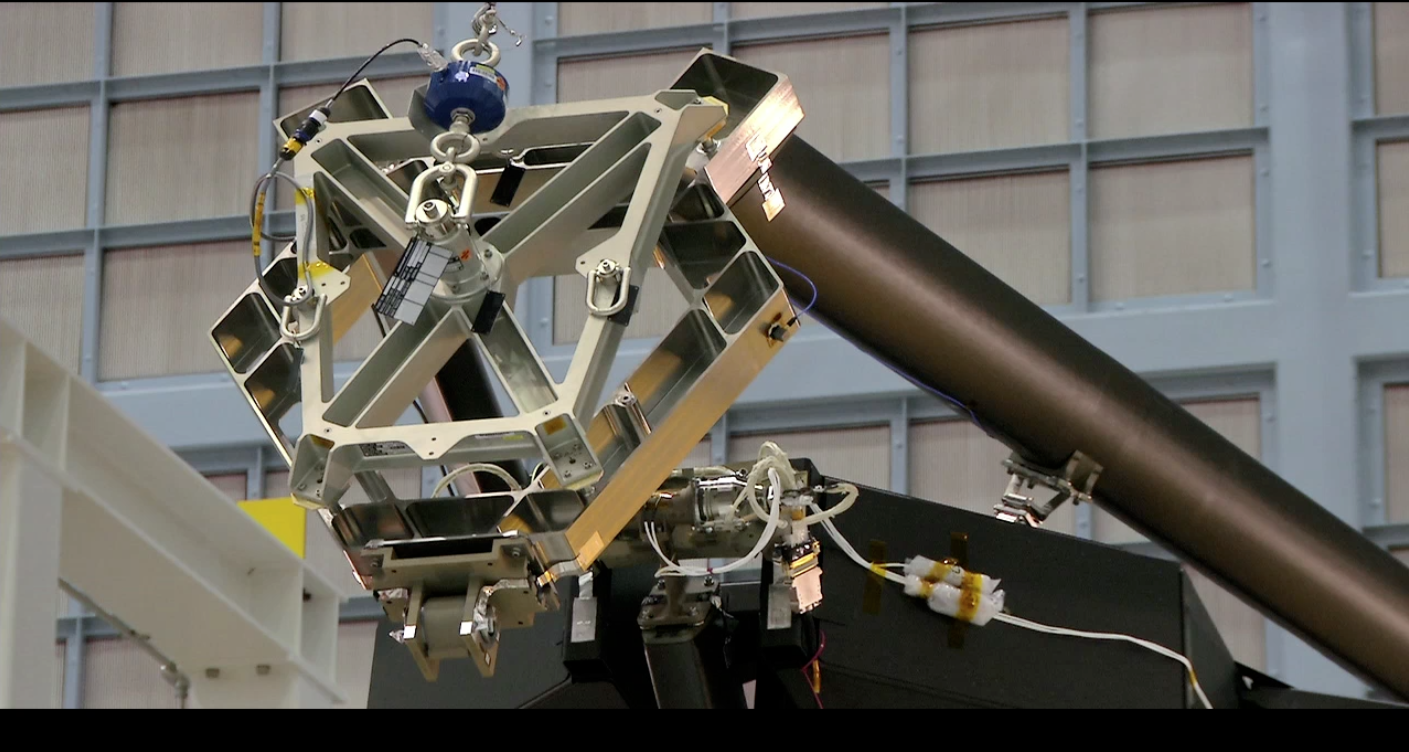

The Webb Telescope Lifted Off of the Rollover Fixture Before Going onto the Payload Adapter B-Roll

Go to this pageB-roll footage of engineers lifting the Webb Telescope off of the rollover fixture at the Guiana Space Centre in Kourou, French Guiana. ||

The Webb Telescope moved for Fueling at Guiana Space Centre Time-Lapses

Go to this pageTime-lapse footage of engineers moving the Webb Telescope from building S5C to S5B for fueling before being moved into the Ariane V rocket at Guiana Space Centre in Kourou, French Guiana. ||

The Webb Telescope Installed to the Rocket Payload Adapter Ring Time-Lapses

Go to this pageTime-lapse footage of engineers installing the Webb Telescope to the rocket payload adapter ring at Guiana Space Centre in Kourou, French Guiana. ||

The Webb Telescope Lifted off of the Rollover Fixture at Guiana Space Centre Time-Lapses

Go to this pageTime-lapses of engineers lifting the Webb Telescope off of the rollover fixture before installing it to the rocket payload adapter ring at the Guiana Space Centre in Kourou, French Guiana. ||

Shipping Webb: Los Angeles to the Launch Site

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

Transporting and Moving Webb

A collection of all the produced videos, b-roll and time-lapse assets related to transporting Webb and it's components.

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

Assembled Observatory

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

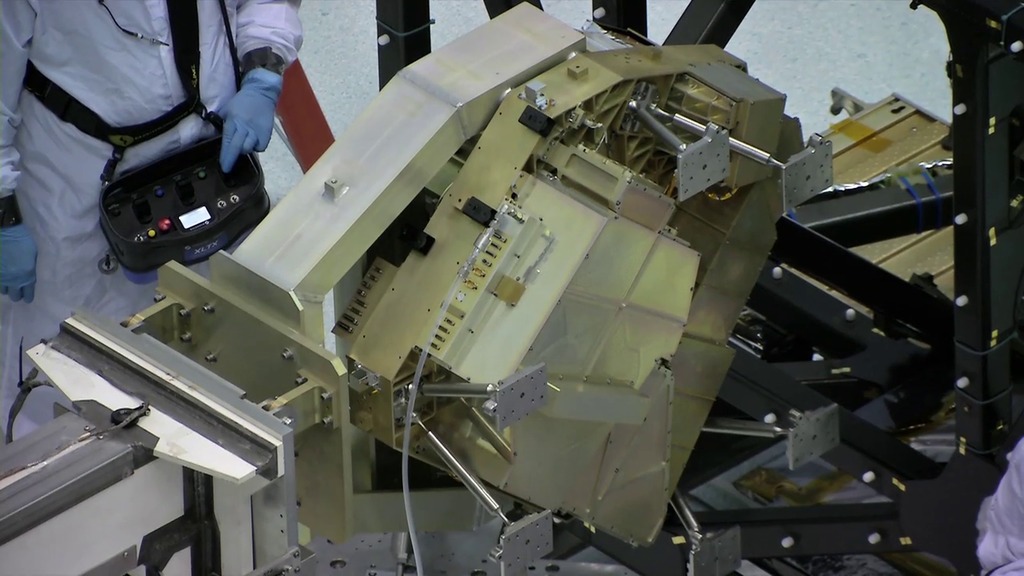

Optics B-Roll

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Section

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- B-Roll

- Produced Video

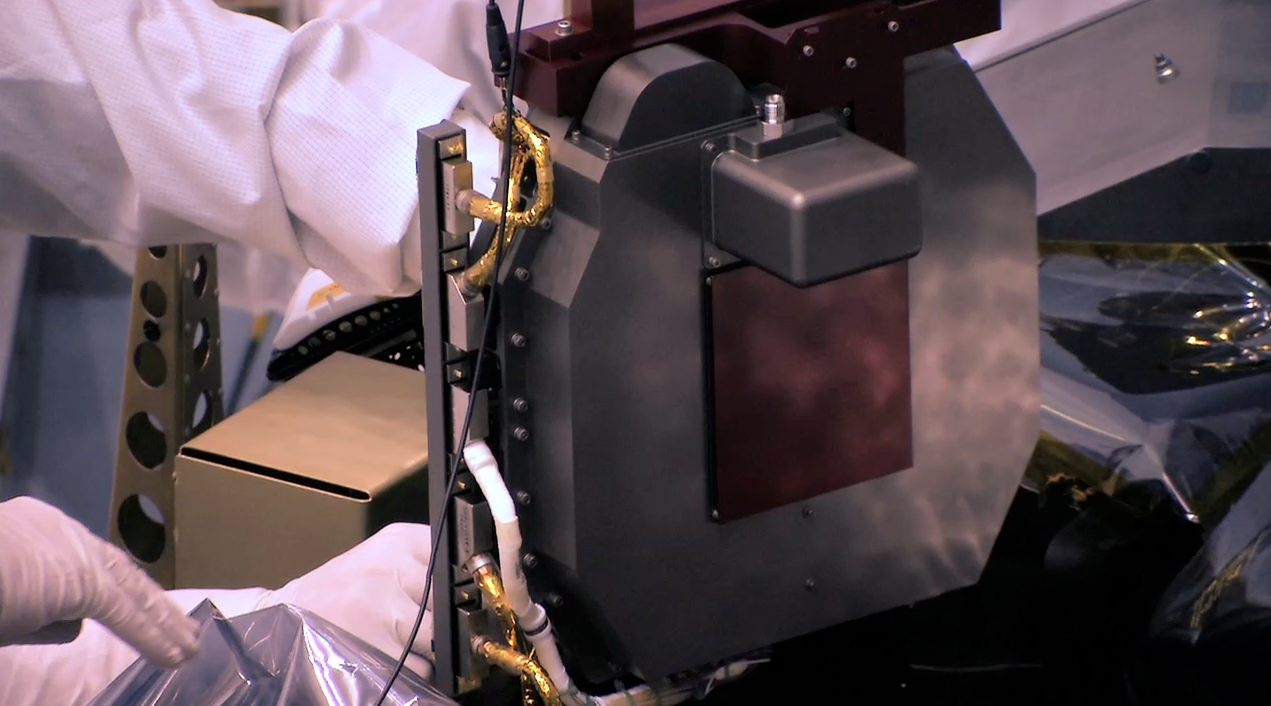

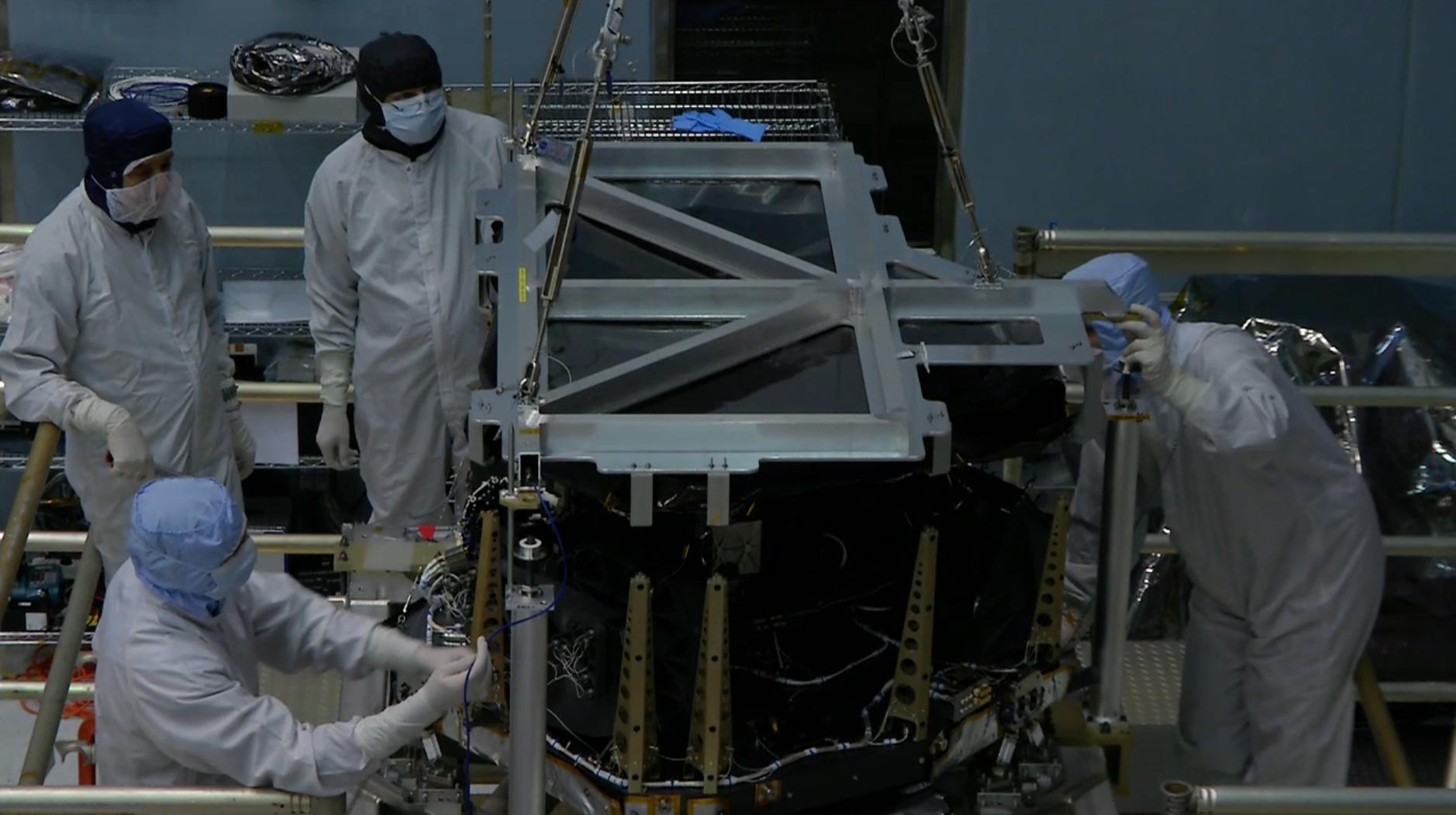

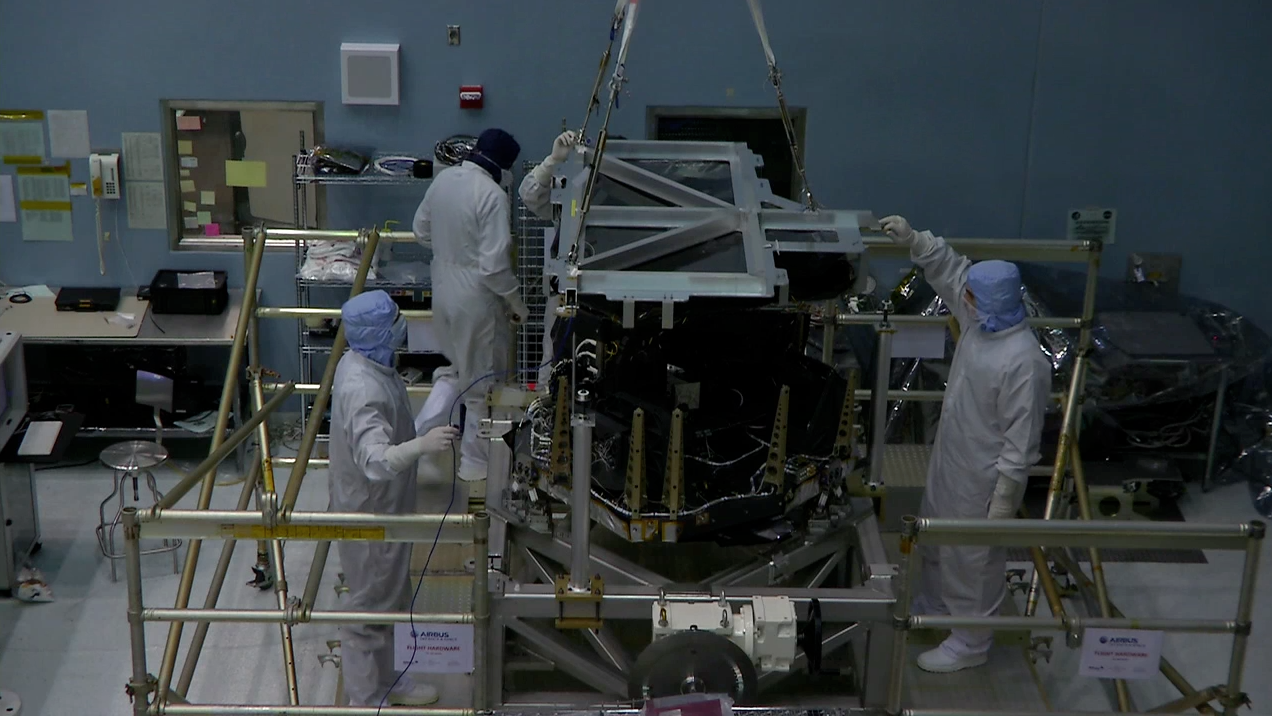

Instrument B-roll

- B-Roll

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

Structure & Component B-roll

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Section

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- B-Roll

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

Timelapse Videos

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

Produced Videos

- Produced Video

- B-Roll

- Animation

- B-Roll

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- B-Roll

- Animation

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Animation

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Section

- Section

- Section

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

- Produced Video

Full Scale Webb Telescope Model

JWST Full Scale Model Construction in Battery Park, NY

Go to this pageThe full-scale model of the James Webb Space Telescope is constructed for the 2010 World Science Festival in Battery Park, NY. The model takes about five days to construct. This video contains a time-lapse sequence of the construction process. ||

Webb AR App Media

- Section

![NASA’s Webb Telescope has discovered a new molecule in Titan’s atmosphere – one that may have implications for the future of this surprisingly Earthlike world.Complete transcript available.Universal Production Music: “Barfuß Durch Die Stadt” by Edgar Möller [GEMA] and Lucia Wilke [GEMA]; “Into the Void” by Gage Boozan [ASCAP]; “Pulse of Progress” by Emma Zarobyan [SOCAN]; “Playing With The Narrative” by Cathleen Flynn [ASCAP] and Micah Barnes [BMI]; “Back From The Brink” by Daniel Gunnar Louis Trachtenberg [PRS]Watch this video on the James Webb Space Telescope YouTube channel.](/vis/a010000/a014800/a014843/Webb_Titan_Climate_Thumbnail.jpg)

![Webb Mission Overview 2023 videoExpanding Time and Space (c) 2016, Atmosphere Music Ltd. [PRS], Daniel Jay Nielsen Promised Lands (c) 2021, Atmosphere Music Ltd. [PRS], Enrico Cacace [BMI], Lorenzo Castellarin [BMI]](/vis/a010000/a014300/a014381/Webb_Mission_Overview_2023_Cover_Image_3_print.jpg)

![4K and HD versions of How Webb captures the Universe video. Odyssey (c) August 29, 2000, Primetime Productions Ltd [PRS], Anders Eliasson [STIM], Steve Martin [PRS]](/vis/a010000/a014300/a014347/Unfolding_the_Universe_with_Webb_Cover_Image_print.jpg)

![Designing Webb FeatureAttention to Detail, (C) 2022, Model Music [PRS], Paul Richard O'Brien [PRS] Theo Maximilian Goble [PRS]Conceptual Scheme, (C) 2021, Koka Media [SACEM], Universal Production Music France [SACEM], Laurent Dury [SACEM]Moving Forward, (C) 2021, Atmosphere Music Ltd. [PRS], Mark Russell [PRS]Relentless Data, (C) 2020, Atmosphere Music Ltd. [PRS], Jay Price [PRS]Life Cycles, (C) 2016, Atmosphere Music Ltd. [PRS], Theo Golding [PRS]](/vis/a010000/a014100/a014185/Designing_Webb_Cover_Image_1.jpg)

![Social Media video Broad Horizons(c)2019, Atmosphere Music Ltd. [PRS], Christopher Timothy White [PRS]](/vis/a010000/a013300/a013375/JWST_Orbit_video_Cover_Image_4_print.jpg)

![Spacecraft assembly, and sunshield deployment milestones. Song: Everlasting Force, copyright, 2015, Atomsphere Music Ltd [PRS]](/vis/a010000/a013500/a013558/Webb’s_Optical_Element_is_assembled_with_its_Spacecraft_and_Sunshield_Segment_Cover_Image_B_print.jpg)

![Complete transcript available.Music Credit: Epic Ascent by Chris White [Killer Tracks]](/vis/a010000/a013000/a013005/13005_-_Why_Do_We_Love_Space_large.00185_print.jpg)