Comet ISON

Overview

Catalogued as C/2012 S1, Comet ISON was first spotted 585 million miles away in September 2012. This is ISON's very first trip into the inner solar system. That means it is still made of pristine matter from the earliest days of the solar system’s formation, its top layers never having been lost by a trip near the sun. Along Comet ISON's journey, NASA has used a vast fleet of spacecraft and Earth-based telescopes to learn more about this time capsule from when the solar system first formed.

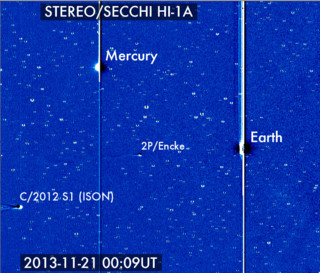

During the last week of its inbound trip, ISON will enter the fields of view of NASA’s space-based solar observatories. Comet ISON will be viewed first by NASA's Solar Terrestrial Relations Observatory, or STEREO. Next the comet will be seen in what’s called coronagraphs by both STEREO and the joint European Space Agency/NASA Solar and Heliospheric Observatory, or SOHO. Then, NASA’s Solar Dynamics Observatory will view the comet for a few hours during its closest approach to the sun, known as perihelion.

Comet ISON Imagery

NASA's Solar Observing Fleet Watch Comet ISON's Journey Around the Sun

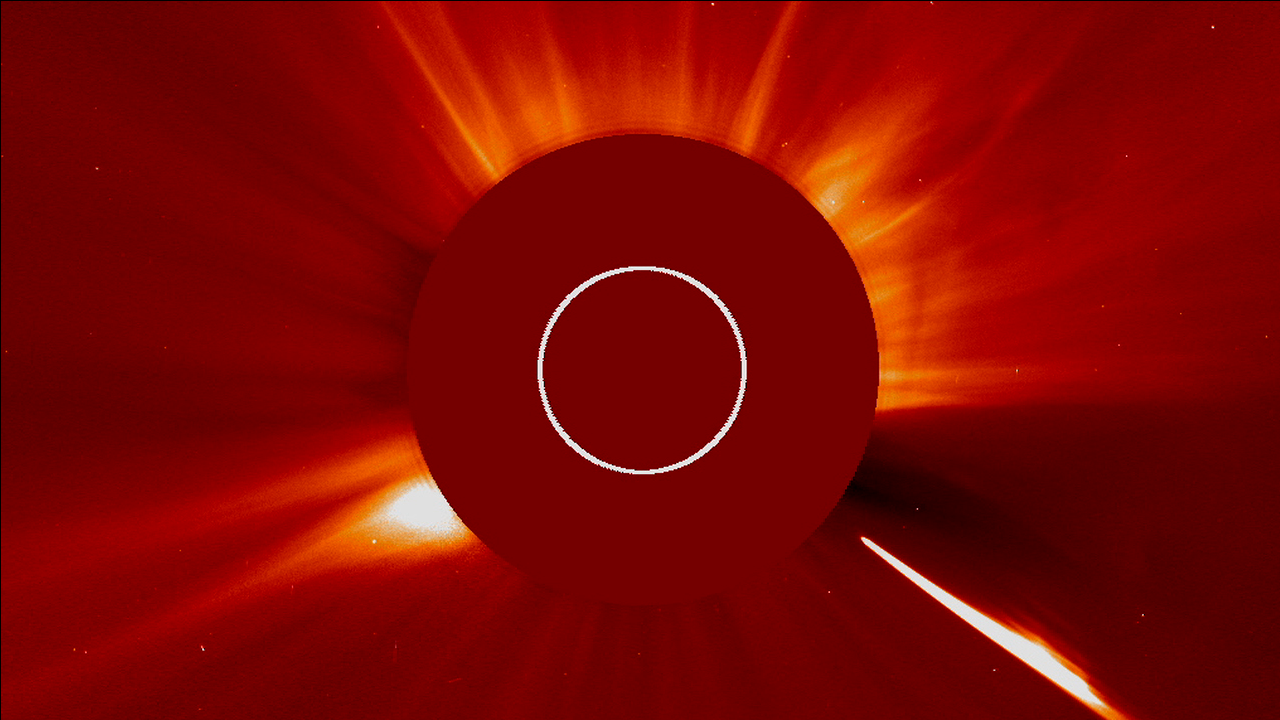

Go to this pageAfter several days of continued observations, scientists continue to work to determine and to understand the fate of Comet ISON: There's no doubt that the comet shrank in size considerably as it rounded the sun and there's no doubt that something made it out on the other side to shoot back into space. The question remains as to whether the bright spot seen moving away from the sun was simply debris, or whether a small nucleus of the original ball of ice was still there. Regardless, it is likely that it is now only dust. The comet was visible in instruments on NASA's Solar Terrestrial Relations Observatory, or STEREO, and the joint European Space Agency/NASA Solar and Heliospheric Observatory, or SOHO, via images called coronagraphs.Watch this video on the NASA Goddard YouTube channel.Credit:NASA/STEREO/ESA/SOHO/SDOGSFC || STEREO_A_Cor2_Still.jpg (1280x720) [494.6 KB] || STEREO_A_Cor2_Still_web.png (320x180) [67.2 KB] || ISON_Full_ProRes_1280x720_29.97.mov (1280x720) [810.6 MB] || ISON_Full_H264_Best_1280x720_29.97.mov (1280x720) [517.2 MB] || ISON_Full_H264_Good_1280x720_29.97.mov (1280x720) [124.1 MB] || ISON_Full_FINAL_youtube_hq.mov (1280x720) [124.1 MB] || ISON_Full_FINAL_1280x720.wmv (1280x720) [49.4 MB] || ISON_Full_FINAL_appletv.m4v (960x540) [46.4 MB] || ISON_Full_H264_1280x720_30.mov (1280x720) [43.1 MB] || ISON_Full_MPEG4_1280X720_29.97.mp4 (1280x720) [28.0 MB] || ISON_Full_FINAL_appletv.webmhd.webm (960x540) [16.6 MB] || ISON_Full_FINAL_ipod_lg.m4v (640x360) [17.5 MB] || ISON_Full_FINAL.mp4 (320x240) [8.3 MB] || ISON_Full_FINAL_ipod_sm.mp4 (320x240) [8.3 MB] ||

Comet ISON before and during Perihelion

Go to this pageAfter a year of observations, scientists waited with bated breath on Nov. 28, 2013, as Comet ISON made its closest approach to the sun, known as perihelion. Would the comet disintegrate in the fierce heat and gravity of the sun? Or survive intact to appear as a bright comet in the pre-dawn sky? Some remnant of ISON did indeed make it around the sun, but it quickly dimmed and fizzled as seen with NASA's solar observatories. This does not mean scientists were disappointed, however. On Dec. 10, 2013, researchers presented science results from the comet's last days at the 2013 Fall American Geophysical Union meeting in San Francisco, Calif. They described how this unique comet lost mass in advance of reaching perihelion and most likely broke up during its closest approach, as well, as summarized what this means for determining what the comet was made of. The panel shared results from the Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO), the Solar Terrestrial Relations Observatory (STEREO), the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) and MESSENGER to present a picture of ISON's trip around the sun, which appears to have led to its demise. The panel also reported on why ISON was not seen in images from the Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO). ||

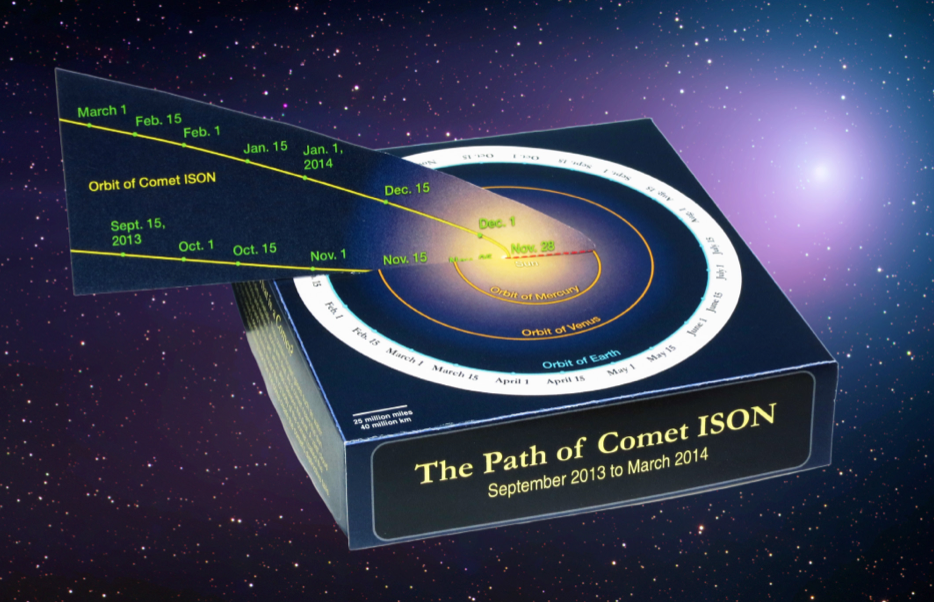

The Path of Comet ISON

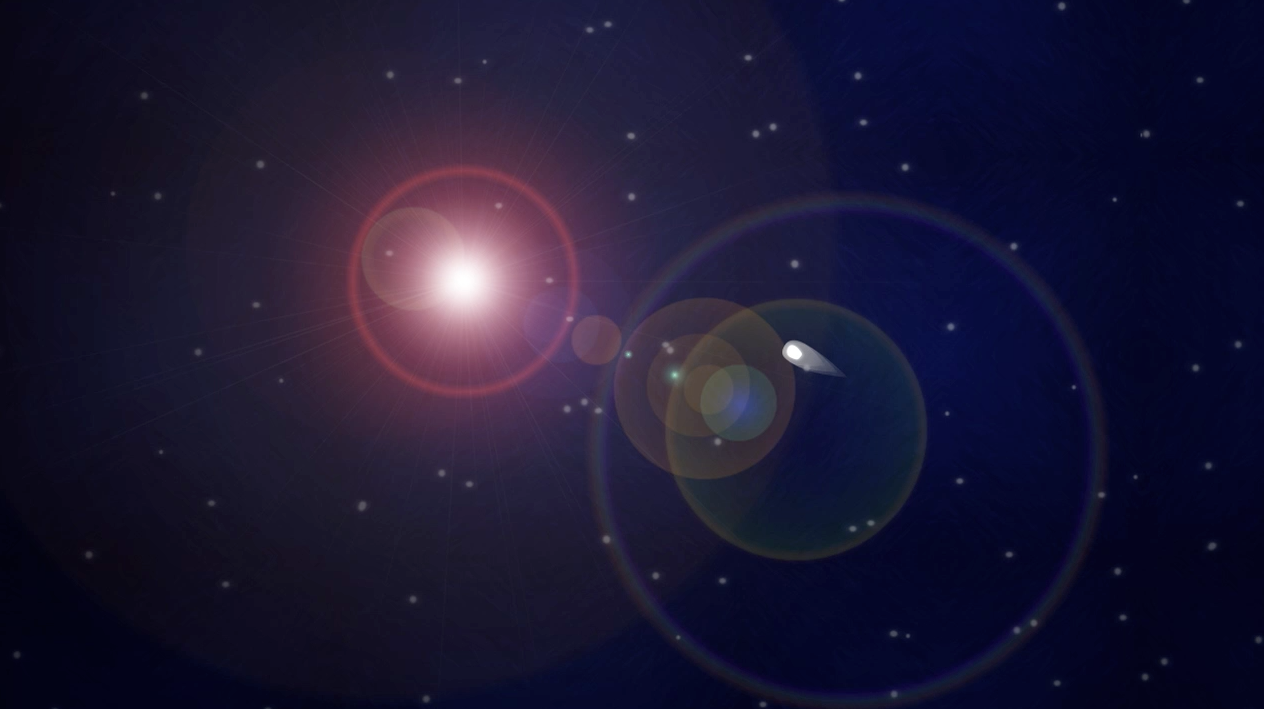

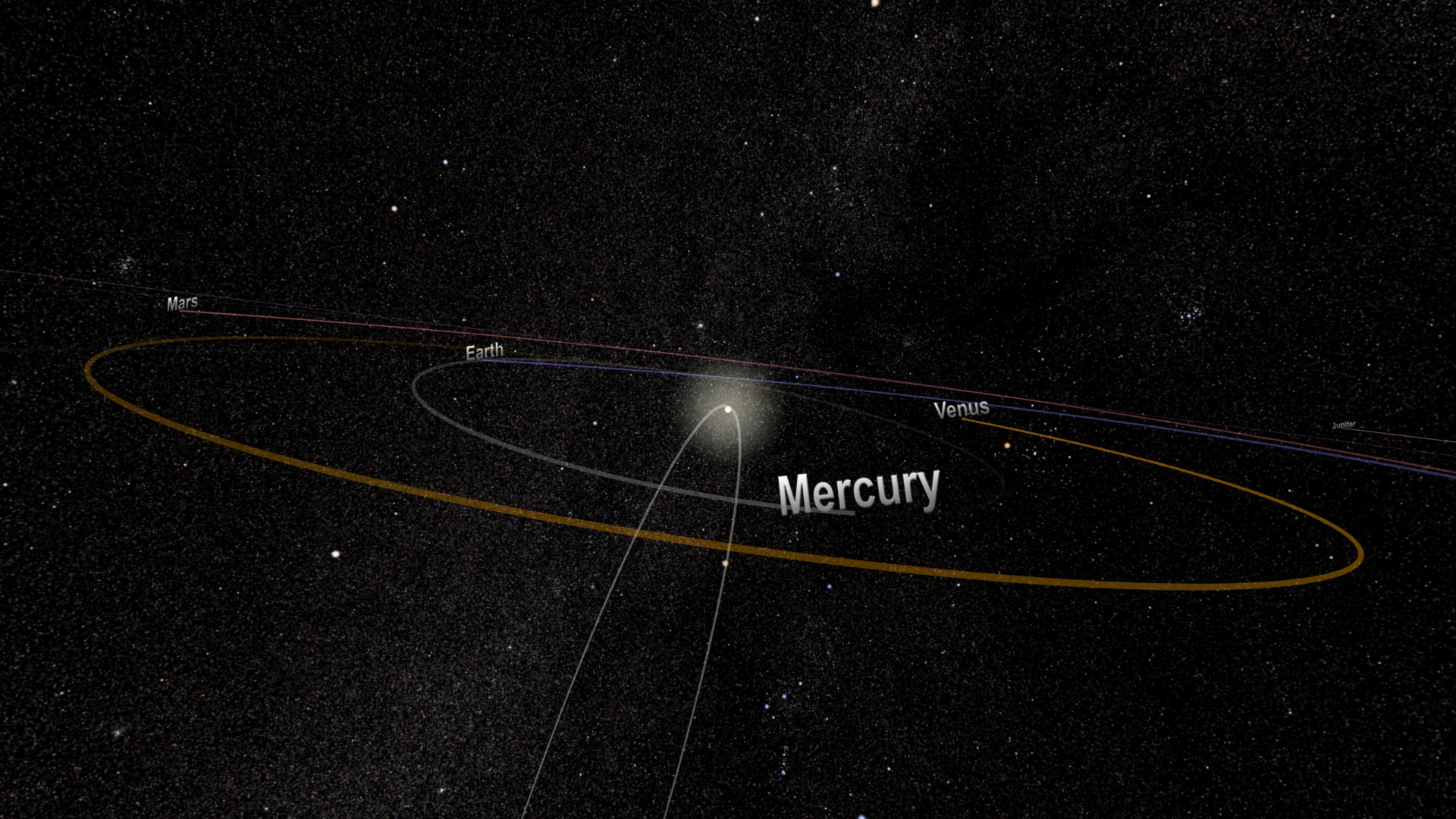

Go to this pageComet C/2012 S1, better known as comet ISON, may become a dazzling sight as it traverses the inner solar system in late 2013. During the weeks before its Nov. 28 close approach to the sun, the comet will be observable with small telescopes, and binoculars. Observatories around the world and in space will track the comet during its fiery trek around the sun. If ISON survives its searing solar passage, which seems likely but is not certain, the comet may be visible to the unaided eye in the pre-dawn sky during December.Watch the animations on this page to visualize ISON's voyage through the inner solar system, or build the paper model of its orbit to track the changing positions of Earth and the comet.Like all comets, ISON is a clump of frozen gases mixed with dust. Often described as "dirty snowballs," comets emit gas and dust whenever they venture near enough to the sun that the icy material transforms from a solid to gas, a process called sublimation. Jets powered by sublimating ice also release dust, which reflects sunlight and brightens the comet. On Nov. 28, ISON will make a sweltering passage around the sun. The comet will approach within about 730,000 miles (1.2 million km) of its visible surface, which classifies ISON as a sungrazing comet. In late November, its icy material will furiously sublimate and release torrents of dust as the surface erodes under the sun's fierce heat, all as sun-monitoring satellites look on. Around this time, the comet may become bright enough to glimpse just by holding up a hand to block the sun's glare.Sungrazing comets often shed large fragments or even completely disrupt following close encounters with the sun, but for ISON neither fate is a forgone conclusion.Following ISON's solar swingby, the comet will depart the sun and move toward Earth, appearing in morning twilight through December. The comet will swing past Earth on Dec. 26, approaching within 39.9 million miles (64.2 million km) or about 167 times farther than the moon.The comet was discovered on Sept 21, 2012, by Russian astronomers Vitali Nevski and Artyom Novichonok using a telescope of the International Scientific Optical Network (ISON) located near Kislovodsk.Learn more about sungrazing comets. ||

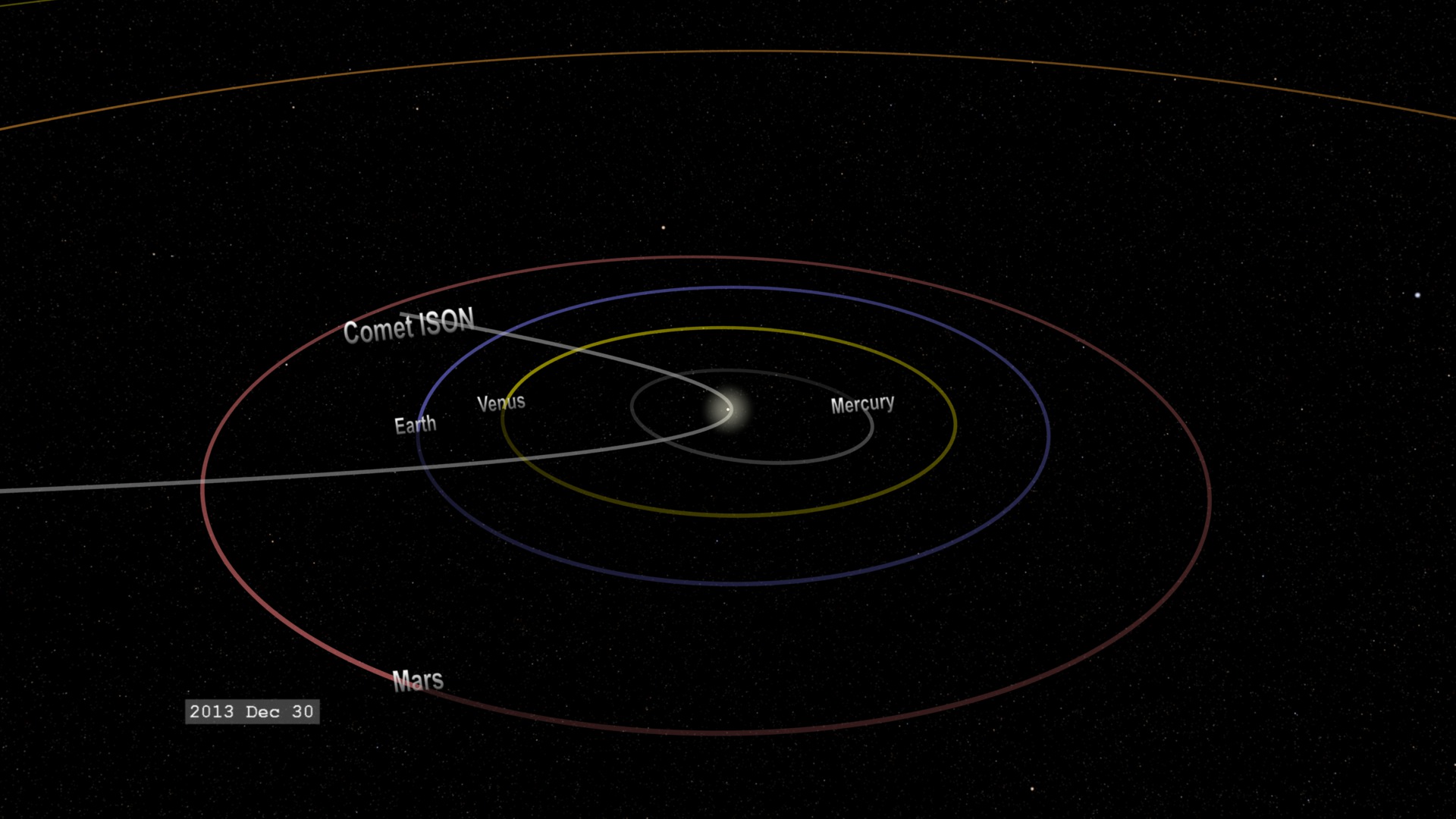

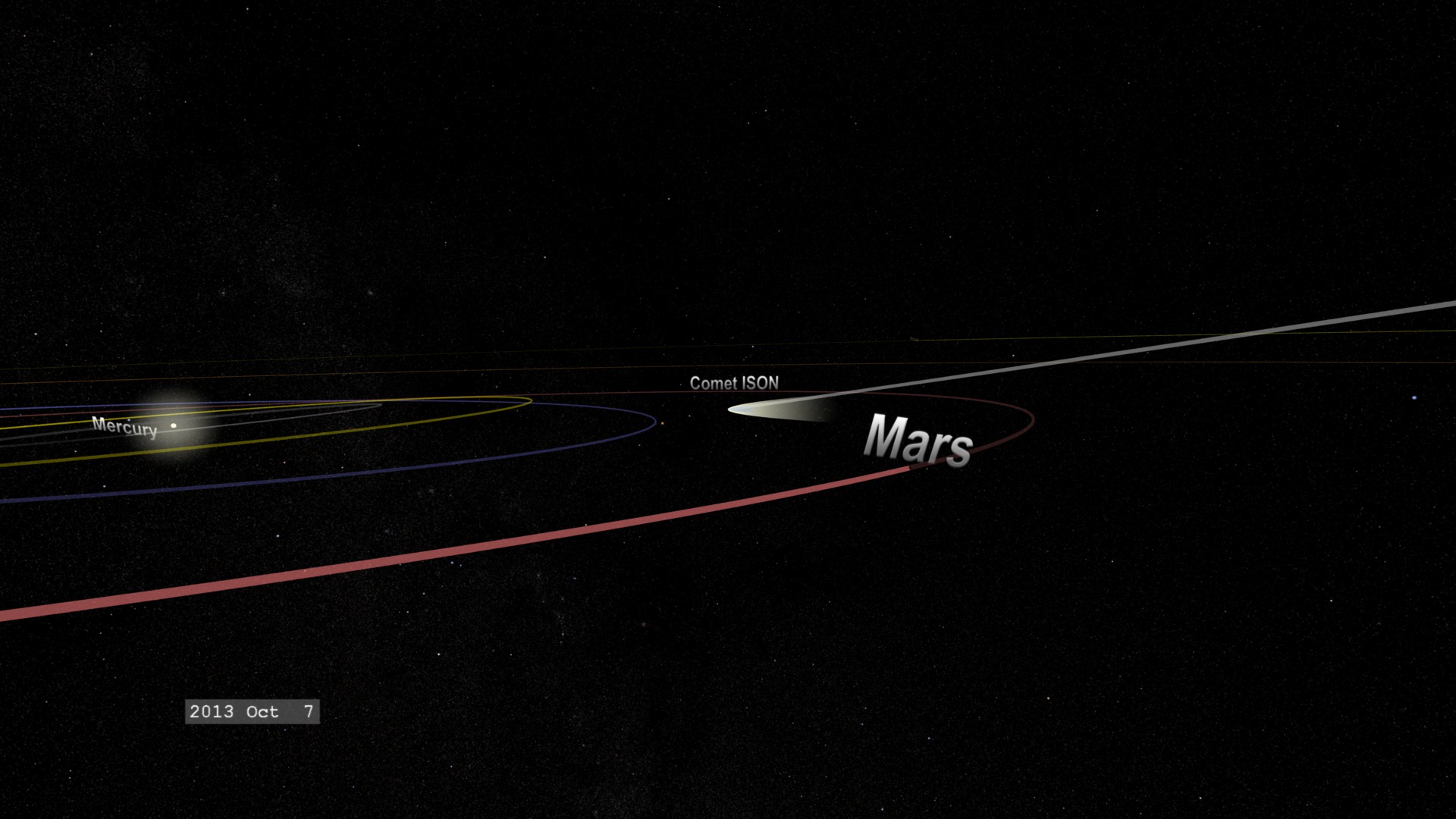

Comet ISON Orbit Visualizations

The Path of Comet ISON

Go to this pageComet C/2012 S1, better known as comet ISON, may become a dazzling sight as it traverses the inner solar system in late 2013. During the weeks before its Nov. 28 close approach to the sun, the comet will be observable with small telescopes, and binoculars. Observatories around the world and in space will track the comet during its fiery trek around the sun. If ISON survives its searing solar passage, which seems likely but is not certain, the comet may be visible to the unaided eye in the pre-dawn sky during December.Watch the animations on this page to visualize ISON's voyage through the inner solar system, or build the paper model of its orbit to track the changing positions of Earth and the comet.Like all comets, ISON is a clump of frozen gases mixed with dust. Often described as "dirty snowballs," comets emit gas and dust whenever they venture near enough to the sun that the icy material transforms from a solid to gas, a process called sublimation. Jets powered by sublimating ice also release dust, which reflects sunlight and brightens the comet. On Nov. 28, ISON will make a sweltering passage around the sun. The comet will approach within about 730,000 miles (1.2 million km) of its visible surface, which classifies ISON as a sungrazing comet. In late November, its icy material will furiously sublimate and release torrents of dust as the surface erodes under the sun's fierce heat, all as sun-monitoring satellites look on. Around this time, the comet may become bright enough to glimpse just by holding up a hand to block the sun's glare.Sungrazing comets often shed large fragments or even completely disrupt following close encounters with the sun, but for ISON neither fate is a forgone conclusion.Following ISON's solar swingby, the comet will depart the sun and move toward Earth, appearing in morning twilight through December. The comet will swing past Earth on Dec. 26, approaching within 39.9 million miles (64.2 million km) or about 167 times farther than the moon.The comet was discovered on Sept 21, 2012, by Russian astronomers Vitali Nevski and Artyom Novichonok using a telescope of the International Scientific Optical Network (ISON) located near Kislovodsk.Learn more about sungrazing comets. ||

Comet ISON Approaches Perihelion

Go to this pageCurrently located beyond the orbit of Jupiter, Comet ISON is heading for a very close encounter with the sun next year. In November 2013, it will pass less than 0.012 Astronomical Units (Wikipedia) (1.8 million kilometers) from the center of the Sun, 1.2 million kilometers from the solar surface. The fierce heating it experiences in that approach could turn the comet into a bright naked-eye object.NOTE: This visualization was revised in March 2013 to fix an ephemeris error. Other enhancements were included in the revision. Also fixed an error where perihelion distance was mistakenly labeled as distance from solar surface. ||

Chasing Comet ISON

Go to this pageComet ISON approaches the inner solar system having just passed the orbit of Jupiter. It passes very close to Mars in early October 2013 before dipping below the ecliptic on its way towards perihelion on November 28, 2013. Comet ISON will make its closest pass to the Earth in January 2014 when it should be visible in the northern hemisphere.In these movies, the cameras chase the comet from two different points of view. ||

General Comet Information

What is a Sungrazing Comet?

Go to this pageSungrazing comets are a special class of comets that come very close to the sun at their nearest approach, a point called perihelion. To be considered a sungrazer, a comet needs to get within about 850,000 miles from the sun at perihelion. Many come even closer, even to within a few thousand miles. Being so close to the sun is very hard on comets for many reasons. They are subjected to a lot of solar radiation which boils off their water or other volatiles. The physical push of the radiation and the solar wind also helps form the tails. And as they get closer to the sun, the comets experience extremely strong tidal forces, or gravitational stress. In this hostile environment, many sungrazers do not survive their trip around the sun. Although they don't actually crash into the solar surface, the sun is able to destroy them anyway. Many sungrazing comets follow a similar orbit, called the Kreutz Path, and collectively belong to a population called the Kreutz Group. In fact, close to 85% of the sungrazers seen by the SOHO satellite are on this orbital highway. Scientists think one extremely large sungrazing comet broke up hundreds, or even thousands, of years ago, and the current comets on the Kreutz Path are the leftover fragments of it. As clumps of remnants make their way back around the sun, we experience a sharp increase in sungrazing comets, which appears to be going on now. Comet Lovejoy, which reached perihelion on December 15, 2011 is the best known recent Kreutz-group sungrazer. And so far, it is the only one that NASA's solar-observing fleet has seen survive its trip around the sun. Comet ISON, an upcoming sungrazer with a perihelion of 730,000 miles on November 28, 2013, is not on the Kreutz Path. In fact, ISON's orbit suggests that it may gain enough momentum to escape the solar system entirely, and never return. Before it does so, it will pass within about 40 million miles from Earth on December 26th. Assuming it survives its trip around the sun. ||

Sungrazers Galore

Go to this pageBefore 1979, there were less than a dozen known sungrazing comets. As of December 2012, we know of 2,500. Why did this number increase? With solar observatories like SOHO, STEREO, and SDO, we have not only better means of viewing the sun, but also the comets that approach it. SOHO allows us to see smaller, fainter comets closer to the sun than we have ever been able to see before. Even though many of these comets do not survive their journey past the sun, they survive long enough to be observed, and be added to our record of sungrazing comets. ||

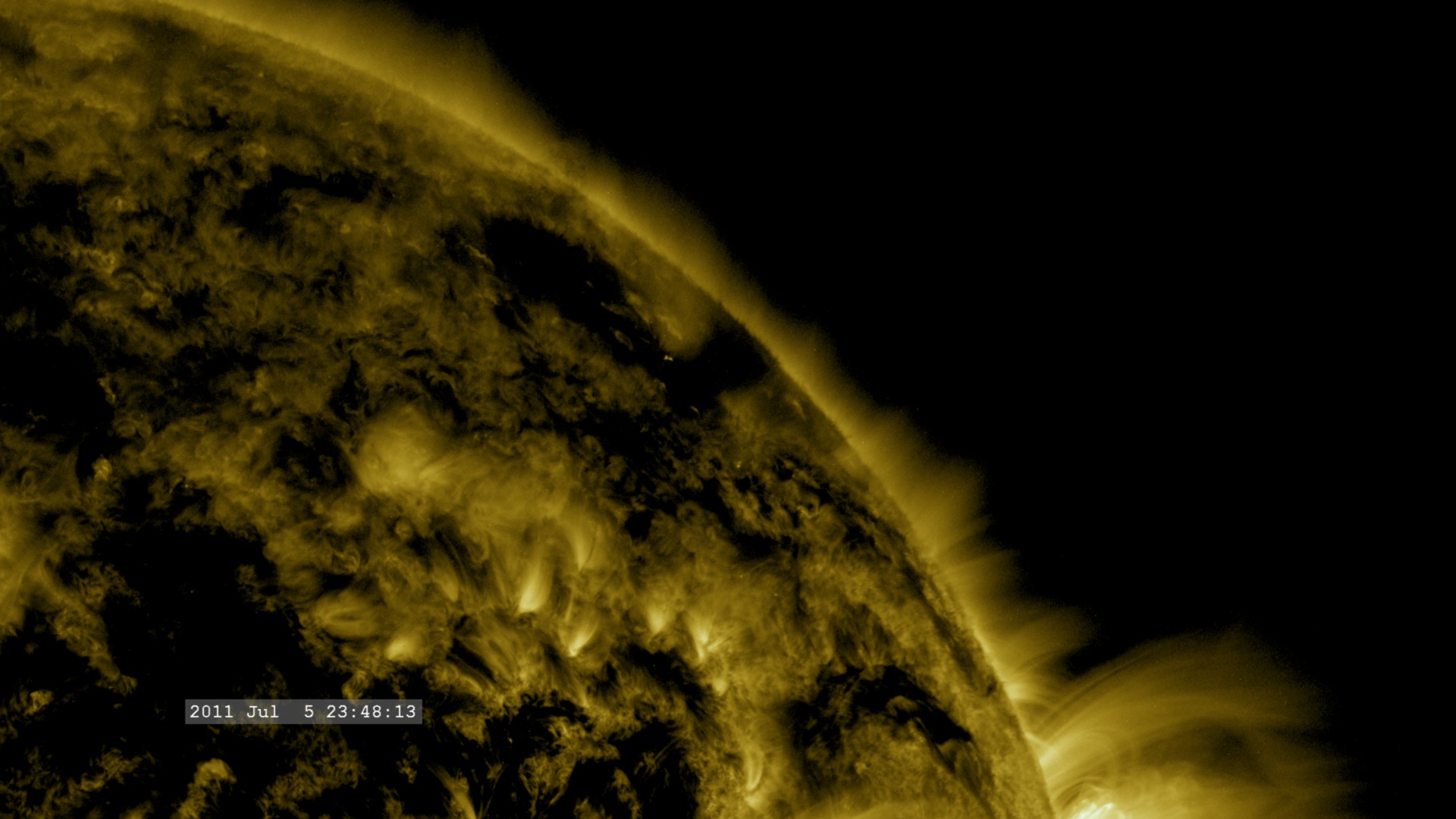

Sun Grazing Comets as Solar Probes

Go to this pageTo observe how winds move high in Earth's atmosphere, scientists sometimes release clouds of barium as tracers to track how the material corkscrews and sweeps around — but scientists have no similar technique to study the turbulent atmosphere of the sun. So researchers were excited in December 2011, when Comet Lovejoy swept right through the sun's corona with its long tail streaming behind it. NASA's Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO) captured images of the comet, showing how its long tail was buffeted by systems around the sun, offering scientists a unique way of observing movement as if they'd orchestrated the experiment themselves. Since comet tails have ionized gases, they are also affected by the sun's magnetic field, and can act as tracers of the complex magnetic system higher up in the atmosphere. Comets can also aid in the study of coronal mass ejections and the solar wind.Watch this video on YouTube. ||

How to Cook a Comet

Go to this pageA comet's journey through the solar syste is perilous and violent. Before it reaches Mars - at some 230 million miles away from the sun - the radiation of the sun begins to cook off the frozen water ice directly into gas. This is called sublimation. It is the first step toward breaking the comet apart. If it survives this, the intense radiation and pressure closer to the sun could destroy it altogether.Animators at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md. created this short movie showing how the sun can cook a comet. Such a journey is currently being made by Comet ISON. It began its trip from the Oort cloud region of our solar system and is now traveling toward the sun. The comet will reach its closest approach to the sun on Thanksgiving Day — Nov. 28, 2013 — skimming just 730,000 miles above the sun’s surface. If it comes around the sun without breaking up, the comet will be visible in the Northern Hemisphere with the naked eye, and from what we see now, ISON is predicted to be a particularly bright and beautiful comet. Even if the comet does not survive, tracking its journey will help scientists understand what the comet is made of, how it reacts to its environment, and what this explains about the origins of the solar system. Closer to the sun, watching how the comet and its tail interact with the vast solar atmosphere can teach scientists more about the sun itself. ||

Kreutz Comet Orbits

Go to this pageHD movie of representative orbit of a sungrazing comet. || Kreutz.noslate_HEEmove.HD1080i.0350.jpg (1920x1080) [582.0 KB] || Kreutz.noslate_HEEmove.HD1080i.0350_web.png (320x180) [92.0 KB] || Kreutz.noslate_HEEmove.HD1080i.0350_thm.png (80x40) [4.5 KB] || Kreutz-Lovejoy_HD1080.mov (1920x1080) [13.2 MB] || Kreutz-Lovejoy_HD1080.mp4 (1920x1080) [13.2 MB] || frames/1920x1080_16x9_30p/ (1920x1080) [64.0 KB] || Kreutz-Lovejoy_HD1080.webmhd.webm (960x540) [2.9 MB] || Kreutz-Lovejoy_iPod.m4v (640x360) [3.0 MB] ||

Other Sungrazing Comets

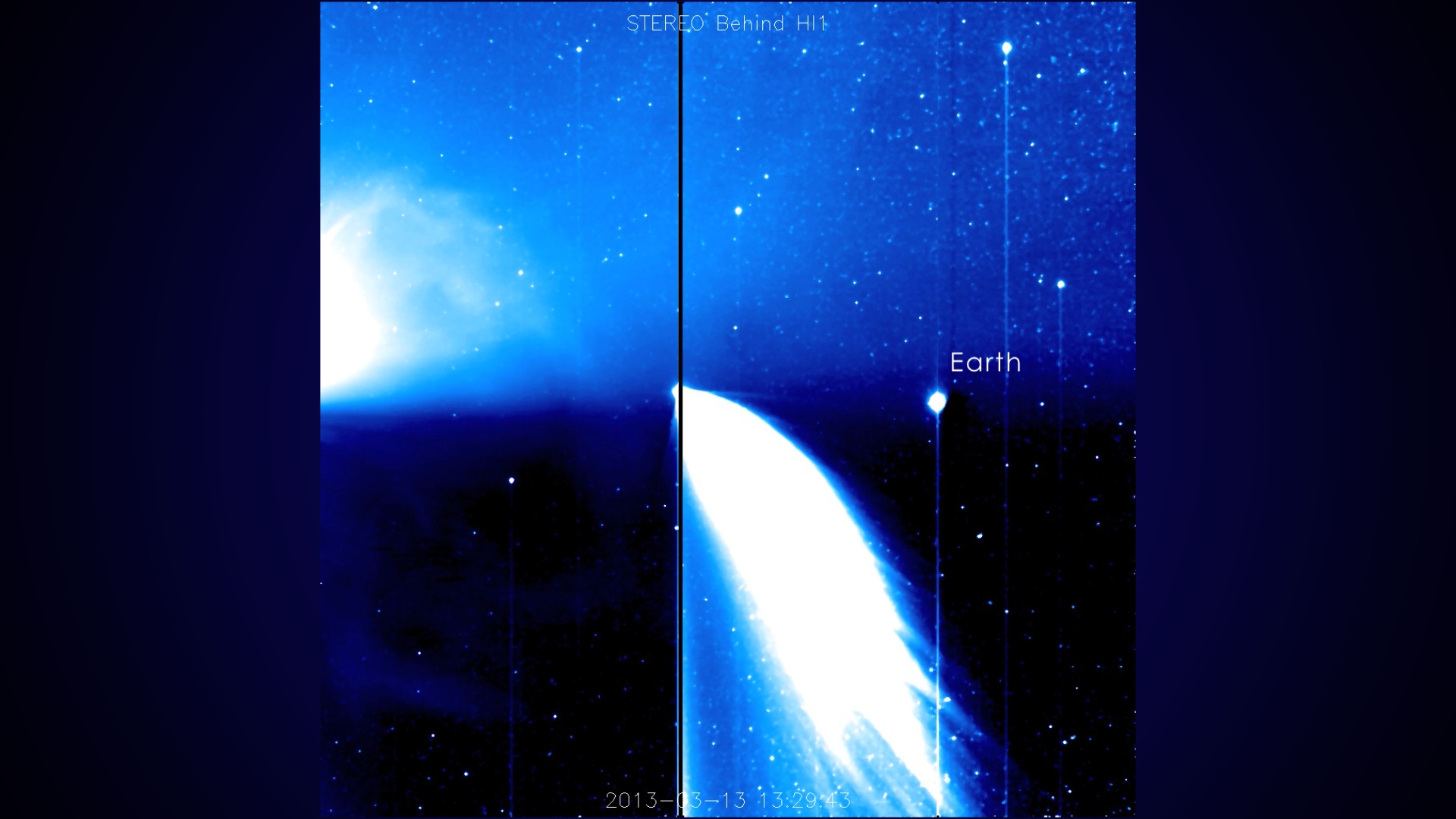

STEREO Watches the Sun Blast Comet PanSTARRS

Go to this pageThis movie from the Solar Terrestrial Relations Observatory (STEREO) shows comet PanSTARRS as it moved around the sun from March 10-15,2013 (repeated three times). The images were captured by the Heliospheric Imager (HI), an instrument that looks to the side of the sun to watch coronal mass ejections (CMEs) as they travel toward Earth, which is the unmoving bright orb on the right. The bright light on the left comes from the sun and the bursts from the left represent the solar material erupting off the sun in a CME. While it appears from STEREO's point of view that the CME passes right by the comet, the two are not lying in the same plane, which scientists know since the comet's tail didn't move or change in response to the CME's passage. ||

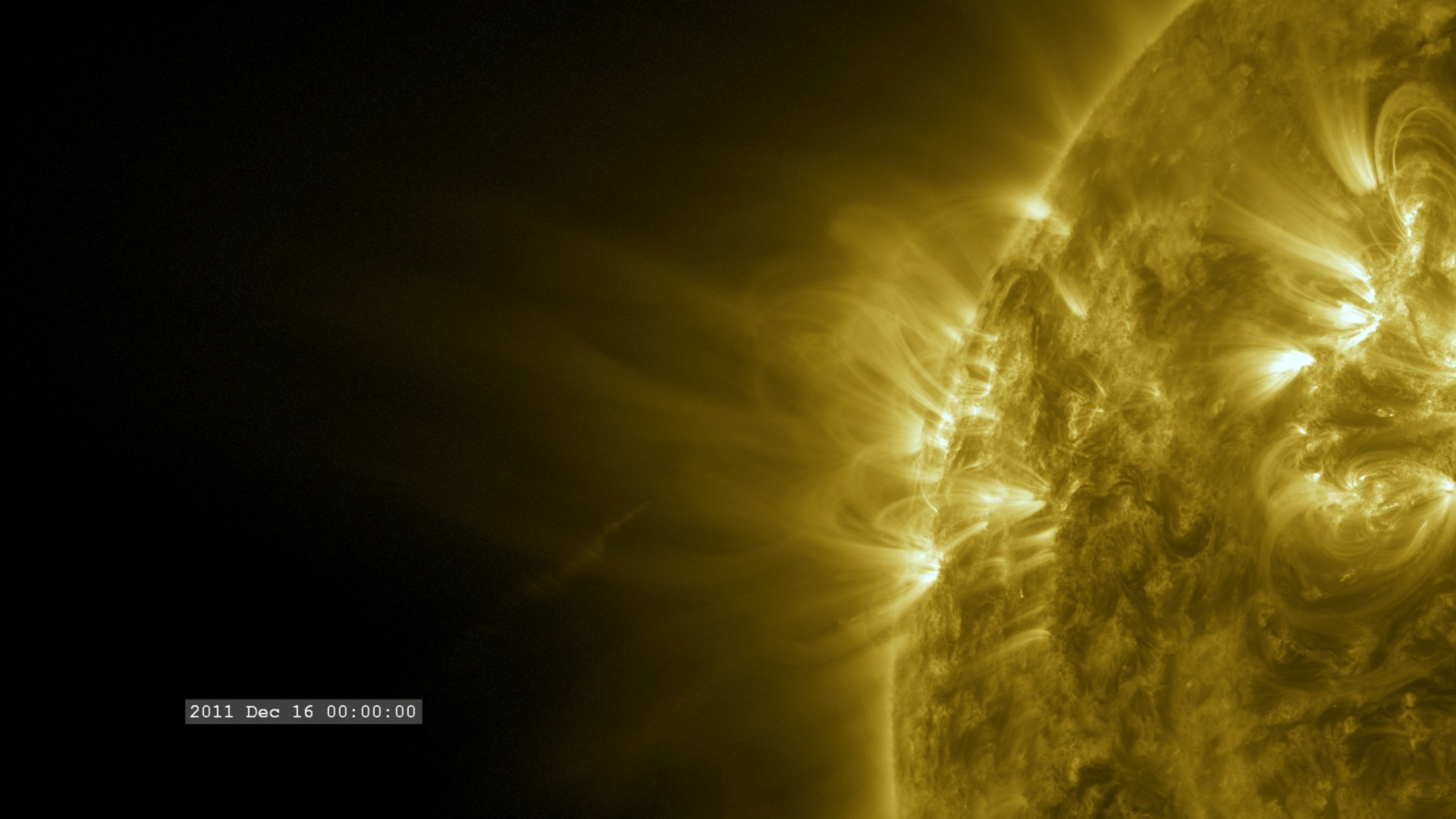

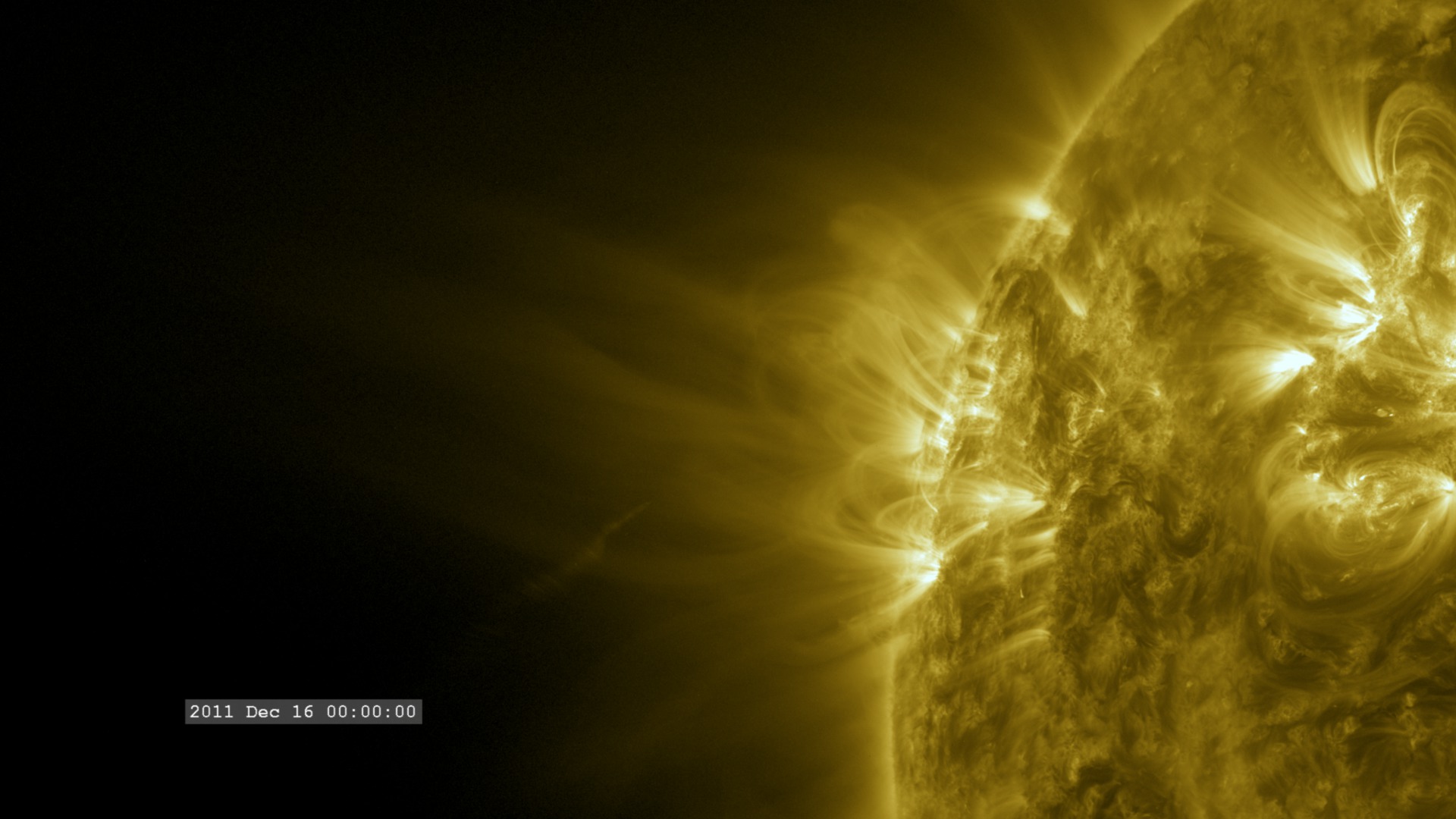

SDO Sees Comet Lovejoy Survive Close Encounter With Sun

Go to this pageOne instrument watching for the comet was the Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO), which adjusted its cameras in order to watch the trajectory. Not only does this help with comet research, but it also helps orient instruments on SDO—since the scientists know where the comet is based on other spacecraft, they can finely determine the position of SDO's mirrors. This first clip from SDO from the evening of Dec 15, 2011 shows Comet Lovejoy moving in toward the sun. Comet Lovejoy survived its encounter with the sun. The second clip shows the comet exiting from behind the right side of the sun, after an hour of travel through its closest approach to the sun. By tracking how the comet interacts with the sun's atmosphere, the corona, and how material from the tail moves along the sun's magnetic field lines, solar scientists hope to learn more about the corona. This movie was filmed by the Solar Dynamics Observatory in 171 angstrom wavelength, which is typically shown in yellow.Credit: NASA/SDO ||

Survivor 2011: Comet Lovejoy vs. The Sun

Go to this pageComet Lovejoy makes a close pass to the Sun, and survives.The Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO) is actually repointed to better observe the comet's approach to the Sun. ||

A Comet's Demise: July 6, 2011

Go to this pageA small comet evaporates away in its flyby of the Sun. || Full resolution 4Kx4K frames || AIA171CometDemise.00390_print.jpg (4096x4096) [2.2 MB] || AIA171CometDemise.00390_web.png (320x320) [90.6 KB] || AIA171CometDemise.mp4 (1080x1080) [9.6 MB] || AIA171CometDemise.webm (1080x1080) [2.5 MB] || frames/4096x4096_1x1_30p/ (4096x4096) [64.0 KB] || AIA171CometDemise-1.mp4 (4096x4096) [198.3 MB] ||

Closeup of Comet Encke from STEREO

Go to this pageThis is a closer view of Comet Encke's collision with a Coronal Mass Ejection (CME) as seen by the STEREO satellite on April 20, 2007. The collision is notable because it completely removed Encke's tail. The blue color here is a gradient added to help make the comet and CME more visible. ||

Comet Encke collides with a CME

Go to this pageNASA's Solar Terrestrial Relations Observatory (STEREO) satellite captured the first images ever of a collision between a coronal mass ejection and a comet. ||