NASA Supercomputer Probes Tangled Magnetospheres of Merging Neutron Stars

New supercomputer simulations explore the tangled magnetic structures around merging neutron stars. These structures, called magnetospheres, interact as the city-sized stars enter their final orbits. Magnetic field lines can connect both stars, break, and reconnect, while currents surge through surrounding plasma moving at nearly the speed of light. The simulations show that these systems may produce X-rays and gamma rays that future observatories should be able to detect.

Credit: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center

Alt text: Narrated video introducing simulations of merging neutron star magnetospheres

Music: “A Theory Develops,” Pip Heywood [PRS], Universal Production Music

Watch this video on the NASA Goddard YouTube channel.

Complete transcript available.

New simulations performed on NASA’s Pleiades supercomputer are providing scientists with the most comprehensive look yet into the interacting magnetic structures around city-sized neutron stars in the moments before they crash. The team identified potential signals emitted during the stars’ final moments that may be detectable by future observatories.

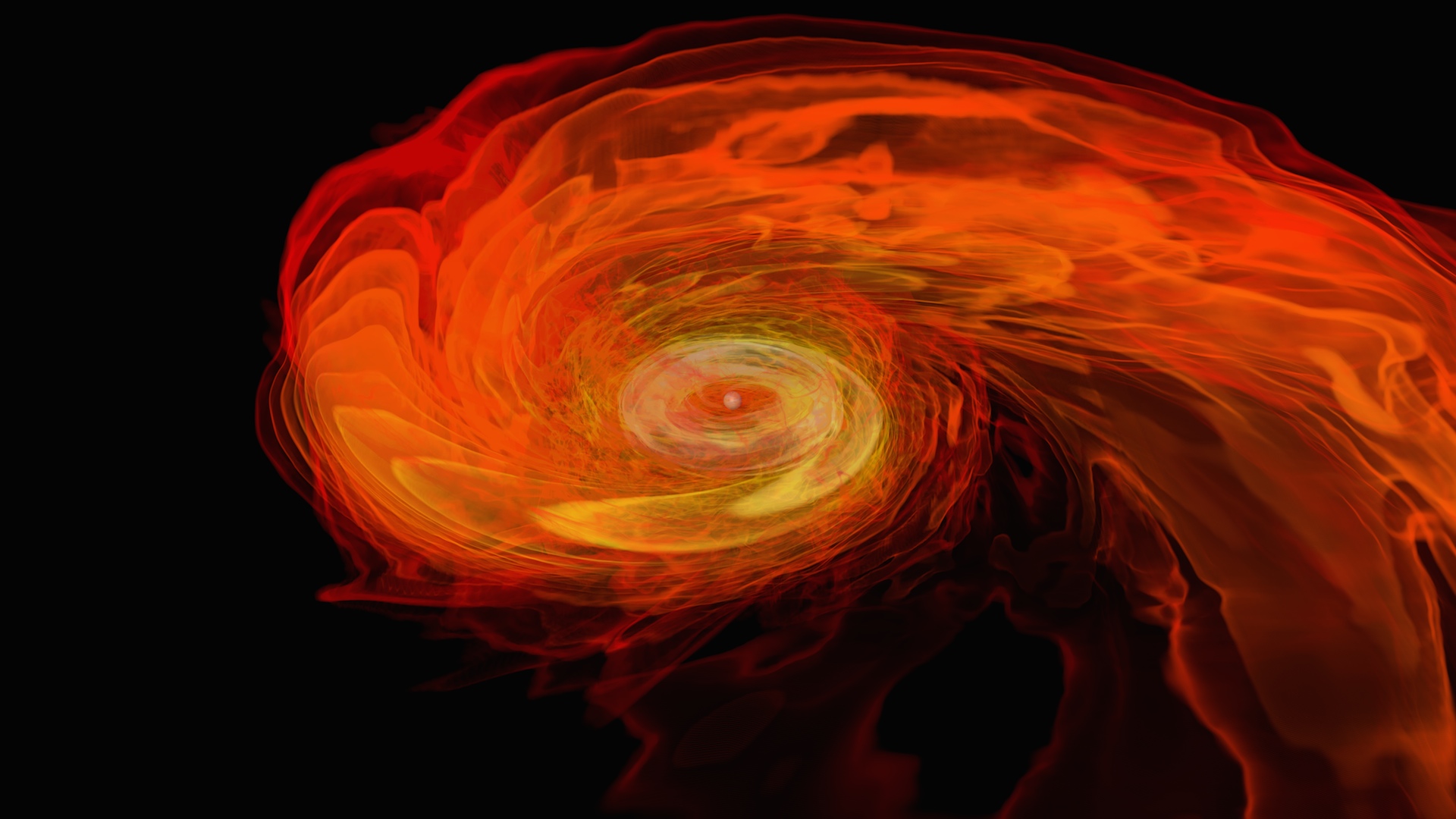

Just before orbiting neutron stars merge, the magnetic fields and plasma around them, called magnetospheres, become entangled. The new simulations studied the last several orbits before the merger, when the magnetospheres undergo rapid and dramatic changes, and modeled potentially observable high-energy signals.

Neutron star mergers produce a particular type of GRB (gamma-ray burst), the most powerful class of explosions in the cosmos. They create near-light-speed jets that emit gamma rays, powerful ripples in space-time called gravitational waves, and a so-called kilonova explosion that forges heavy elements like gold and platinum. So far, only one event, observed in 2017, has connected all three phenomena.

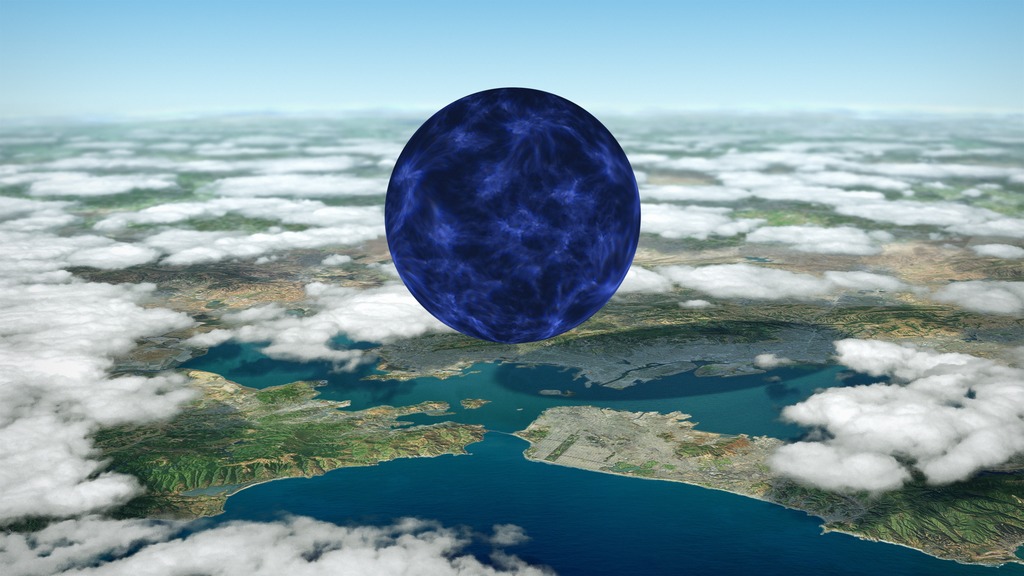

Neutron stars pack more mass than our Sun into a ball about 15 miles (24 kilometers) across, roughly the length of Manhattan Island in New York City. Born out of supernova explosions, neutron stars can spin dozens of times a second and wield some of the strongest magnetic fields known, up to 10 trillion times stronger than a refrigerator magnet. That’s strong enough to directly transform gamma-rays into electrons and positrons and rapidly accelerate them to energies far beyond anything achievable in particle accelerators on Earth.

In the simulations, which were performed on the Pleiades supercomputer at NASA’s Ames Research Center in California’s Silicon Valley, the linked magnetospheres behave like a magnetic circuit that continually rewires itself as the stars orbit. Field lines connect, break, and reconnect while currents surge through plasma moving at nearly the speed of light, and the rapidly varying fields can accelerate particles to high energies.

The team ran hundreds of simulations of a system of two orbiting neutron stars, each with 1.4 solar masses. The goal was to explore how different magnetic field configurations affected the way electromagnetic energy &emdash; light in all of its forms &emdash; left the coalescing system.

The research shows that the emitted light varies rapidly in brightness and is not distributed evenly, so what a far-away observer might detect depends on their perspective on the merger. In addition, the way the signals strengthen as the stars get closer and closer depends on the relative magnetic orientations of the neutron stars.

If next-generation gravitational wave observatories can provide an early warning, future ground-based gamma-ray telescopes will be able to team up with space-based X-ray and gamma-ray telescopes to begin searching for the pre-merger emission seen in these simulations. Routine observation of events like these using two different “messengers” — light and gravitational waves — will provide a major leap forward in understanding this class of GRBs.

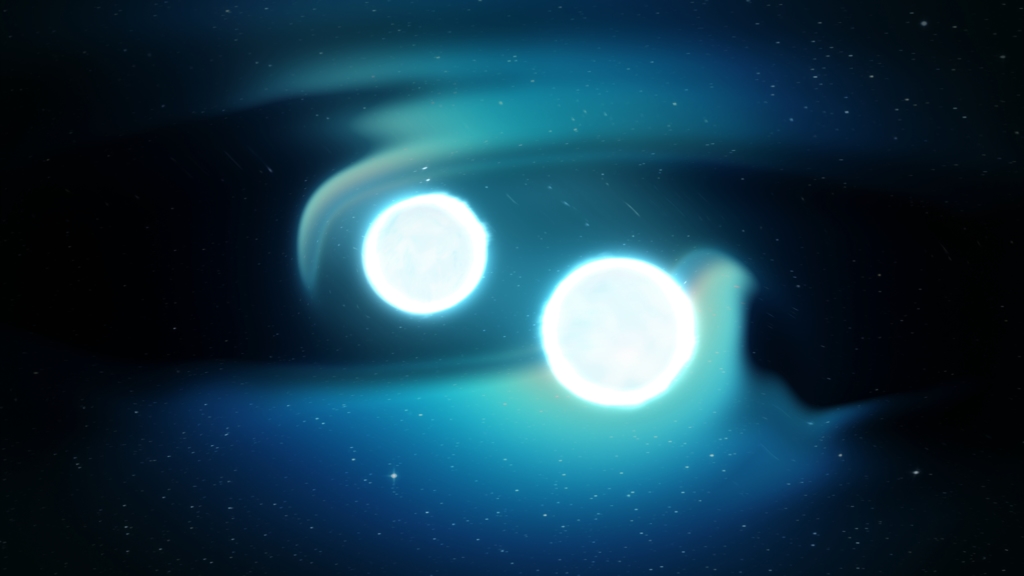

This simulation shows orbiting magnetized neutron stars (gray spheres) beginning about 0.03 seconds before their surfaces come into contact. The stars’ magnetic fields and high-energy plasma strongly interact before they collide, producing electromagnetic energy — light in all its forms — that exits the system. The intensity and direction of this emission varies greatly as the merger proceeds. Brighter colors indicate stronger emission. This view observes the system from the orbital plane of the two neutron stars, which are 34 miles (54 kilometers) apart at the start of the video. The model neutron stars are about 15 miles (24 kilometers) across and contain 1.4 times the Sun’s mass.

Credit: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center/D. Skiathas et al. 2025

Alt text: Orbital plane view of neutron star merger showing electromagnetic emission

Same as above but looking down along the system’s orbital axis.

Credit: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center/D. Skiathas et al. 2025

Alt text: Top view of neutron star merger showing electromagnetic emission

Same as above but looking at the system from 45 degrees above the orbital plane.

Credit: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center/D. Skiathas et al. 2025

Alt text: Oblique view of neutron star merger showing electromagnetic emission

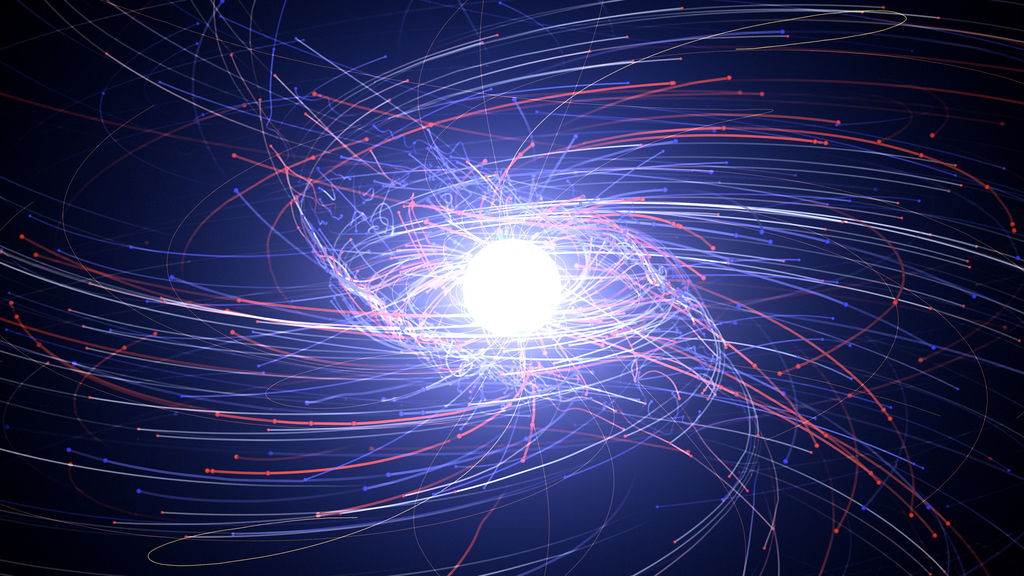

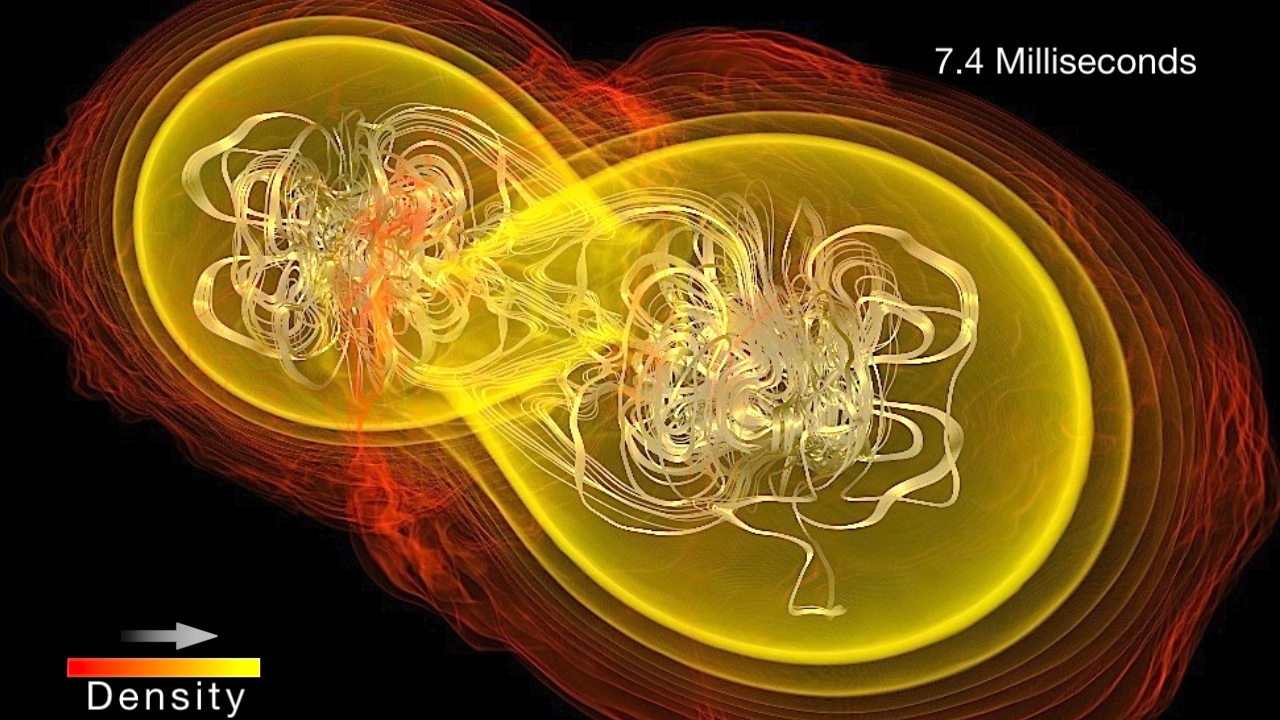

This simulation shows the interacting magnetic field lines of modeled neutron stars (gray spheres) beginning about 0.03 seconds before their surfaces come into contact. Both stars host powerful magnetic fields of the same strength but with different orientations, indicated by magenta arrows. Red and yellow indicate filed lines originating and terminating on the same star. Orange lines connect one star to the other, and gray represents open field lines, which sweep behind the stars as they orbit. As the stars converge, closed field lines break and reconfigure, driving powerful currents through plasma moving near the speed of light.

Credit: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center/D. Skiathas et al. 2025

Alt text: Equatorial view of merging neutron star magnetic fields

Same as above but looking down along the system’s orbital axis.

Credit: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center/D. Skiathas et al. 2025

Alt text: Top view of neutron star merger magnetic field lines

Same as above but looking at the system from 45 degrees above the orbital plane.

Credit: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center/D. Skiathas et al. 2025

Alt text: Oblique view of neutron star merger magnetic field lines

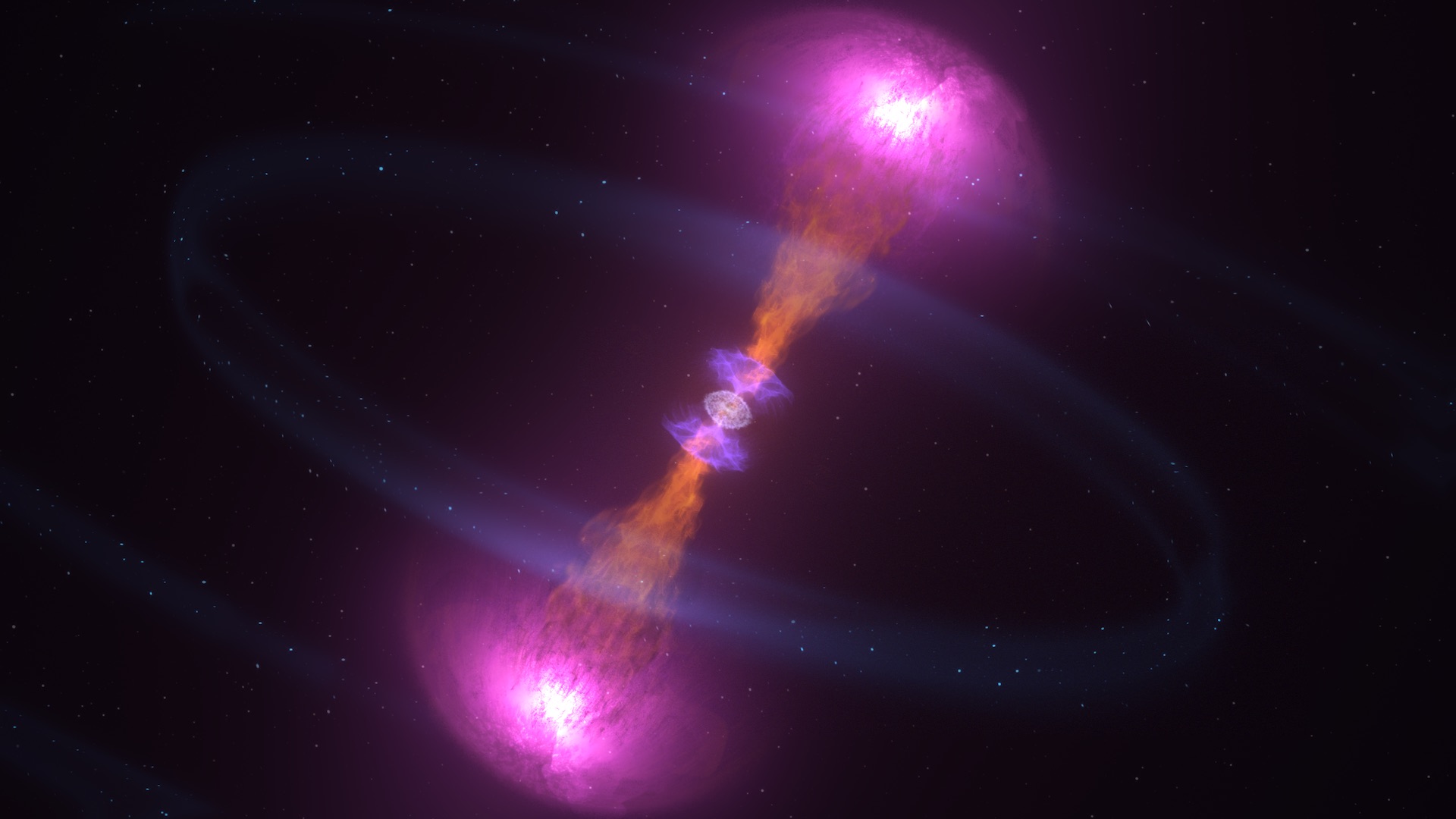

This oblique view of the merging neutron star simulation highlights regions producing the highest-energy light. Brighter colors indicate stronger emission. These regions produce gamma rays with energies trillions of times greater than that of visible light, but likely none of it could escape. That’s because the highest-energy gamma rays quickly convert to particles in the presence of such powerful magnetic fields. However, gamma rays at lower energies, with millions of times the energy of visible light, can exit the merging system, and the resulting particles may also radiate at still lower energies, including X-rays. The emission varies rapidly and is highly directional, but it could potentially be detected by future facilities.

Credit: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center/D. Skiathas et al. 2025

Alt text: Simulation showing highest-energy light from merging neutron stars

Shorter vertical version of the narrated video. Versions with and without on-screen text for the narration are available (the no-text version has "NoToS" in the file name).

Credit: NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center

Alt text: Short narrated video introducing simulations of merging neutron star magnetospheres

Music: “A Theory Develops,” Pip Heywood [PRS], Universal Production Music

Complete transcript available.

For More Information

See NASA.gov

Credits

Please give credit for this item to:

NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center. However, individual items should be credited as indicated above.

-

Producer

- Scott Wiessinger (eMITS)

-

Science writer

- Francis Reddy (University of Maryland College Park)

-

Scientists

- Dimitrios Skiathas (Southeastern Universities Research Association)

- Constantinos Kalapotharakos (NASA/GSFC)

- Demosthenes Kazanas (NASA/GSFC)

- Zorawar Wadiasingh (University of Maryland, College Park)

Series

This page can be found in the following series:Related papers

Magnetosphere Evolution and Precursor-driven Electromagnetic Signals in Merging Binary Neutron Stars. Dimitrios Skiathas et al 2025 ApJ 994 131

Release date

This page was originally published on Thursday, January 29, 2026.

This page was last updated on Thursday, January 22, 2026 at 10:17 AM EST.