|

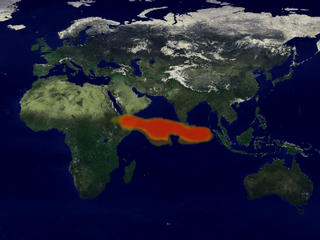

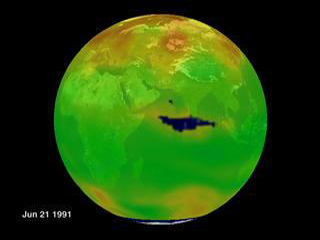

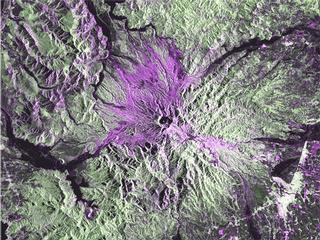

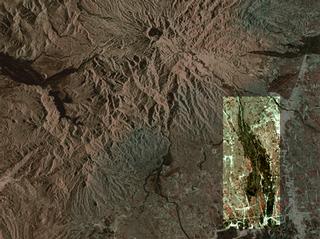

June 15, 2001 marks the tenth anniversary of the eruption of Mt. Pinatubo, one of the most destructive volcanic eruptions of the last century. Found on the Bataan Peninsula on the island of Luzon in the Philippines, the volcano had been dormant for 500 years when clouds of sulfur dioxide and tons of ash spewed from the crater. Ultimately over 600 lives were lost in the explosion and its aftermath. In addition to the devastation on the ground, however, the eruption had far reaching effects on our global atmosphere. Spreading sulfur dioxide and dust into the stratosphere affected both global temperature and Earth?s protective layer of ozone. Click here for print res image Landsat Looks at Mt. Pinatubo This recent false color Landsat-7 image, from January 2001, shows Mt. Pinatubo as it stands today. The caldera is seen in the middle of the image, underneath clouds. Ten years after the blast, vegetation is re-growing on the slopes of the mountain (in green.) Streams of mud, called lahars, (resulting from ash from the eruption mixing with water- seen as the lighter sediment) continue to flow down the sides of the mountains, as well as channels of water (darker streams). However, as vegetation grows back, the ash becomes more stabilized and less likely to form the destructive lahars. Image Courtesy: NASA/USGS/University of Hawaii Sulfur Dioxide After the Eruption Click here for an animation of the sulfur cloud and for print res images Click here for images without dates The eruption of Mt. Pinatubo blasted a huge cloud of sulfur dioxide, shown in red, into the stratosphere. This data taken from NASA's Total Ozone Mapping Spectrometer (TOMS) instrument shows that initial burst of sulfur dioxide and its international path in the days following the eruption, from June 16th to June 30th. The sulfur gas cloud dissipates as the gas turns into droplets of sulfuric acid. Both the gas and subsequent acid were contributors to the overall dust cloud that cooled the global climate. Image Courtesy: NASA Decrease in the Ozone Levels Click for an animation of the equatorial ozone hole and for print res images During the year and a half after the eruption, global stratospheric ozone levels decreased as a result of chemical reactions with the ozone and the sulfur dioxide gases released by the volcano. However, the initial effect of the injection of sulfur dioxide into the atmosphere was so strong, that a small hole was created in the ozone layer, (from June 15th, 1991 through June 30, 1991) as seen here, in blue, using TOMS data. This visualization shows global ozone levels before and after the eruption. After the hole dissipates, continued low levels of ozone, in very light blue, can be seen around the tropics. Image Courtesy: NASA Shuttle Images of the Atmosphere Click here for print res image top left Click here for print res image top right These images highlight the difference in the atmosphere before and after the Mt. Pinatubo eruption. Showing the earth?s limb at sunset, first in September 1984, the atmosphere is relatively clear. The second image, taken in August of 1991, a little more than a month after the eruption, shows distinct layers of aerosols in the upper reaches of the atmosphere. These aerosols eventually made their way around the globe, contributing to a temporary worldwide cooling. Images Courtesy: NASA/ JSC Shuttle Images of Mt. Pinatubo This sequence of images taken from various Space Shuttle missions highlight the evolution of Mt. Pinatubo over time. March of 1982, STS 003: The mountain as it appeared before the eruption and after 500 years of dormancy. At the time of the eruption, many people lived around the volcano. July of 1992, STS 050: One year after the eruption, the summit has been blasted away. STS-046, August 1992: The mudflows are clearly seen trailing down the mountainside. The lahars filled the existing river beds on Mt. Pinatubo STS 080, Nov-Dec. 1996Images Courtesy: NASA/JSC Spacebourne Radar Looks at Pinatubo One of the most devastating impacts of the eruption was the subsequent mud flows, called lahars, that streamed down the side of the mountain. The tons of ash, seen here in great quantity on the western slope, mixed with heavy rainfall to create destructive streams of mud, capable of moving at speeds up to 20 miles per hour. This false color image was taken from the Spacebourne Imaging Radar-C (SIR-C) instrument onboard the Space Shuttle in April of 1994 and highlights the ash in purple. Image Courtesy: NASA/DARA/ASI/University of Hawaii SIR-C Images These false color images, also taken from the Spacebourne Imaging Radar-C (SIR-C) instrument onboard the Space Shuttle, highlight the difference in a lahar before (April 1994) and after (October 1994) the rainy season. After the monsoons, the lahar has widened considerably. Image Courtesy: NASA/DARA/ASI/University of Hawaii |