Cosmic Designs and The Planets

Greetings and welcome to “Cosmic Designs” a performance by the National Philharmonic presented in partnership with NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center.

“Cosmic Designs” is a voyage that blends together science and art. The pursuit of knowledge and the creative drive for artistic expression are inherent to the human condition. The melding of NASA imagery and symphonic music we present here showcases the imagination that underpins both and highlights how inspiring the combination can be.

Title card and greetings to performances of "The Planets", presented in partnership with NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center. Includes credits of the producers, editors, animators, and visualizers responsible for the NASA imagery compiled in the seven movements hosted on this page.

Textless version of the title card to the performance of "The Planets", presented in partnership with NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center.

From the oceans of Earth, to the ocean of the stars, we come to the centerpiece of tonight’s performance.

Most of Earth’s planetary neighbors have been known for thousands of years, but for much of that time, they were not much more than wandering points of light that moved predictably through the sky.

When Holst composed his “Planets” suite a century ago, the best telescopes of the time were only just beginning to reveal the true nature of the planets. Holst drew his inspiration from Roman myth, not fledgling scientific observation.

In some cases, the mythology shares some common ground with what we know today about the planets.

Holst titled his movement on Mars “The Bringer of War.” The driving power of this opening piece evokes the Red Planet’s towering dormant volcanoes and battered cratering. The solar system’s biggest canyon is like a battle scar across Mars’ torso. Mars can be a downright hostile place!

It’s also a far more active world than you might think.

NASA’s orbiters, landers and rovers see small tornados wisp across the surface. We see new craters from new impacts. We see water vaporizing into a thin Martian atmosphere that the solar wind rips away.

The more we’ve learned about Mars today, the more we’ve learned about Mars of the past.

We don’t think Mars ever hosted vast civilizations, but Mars was once a wet world, one that may have looked a lot more like Earth. Was there ever life there? Is there life there now?

As you listen to this driving and exciting piece, imagine how amazing the answers to those questions could be.

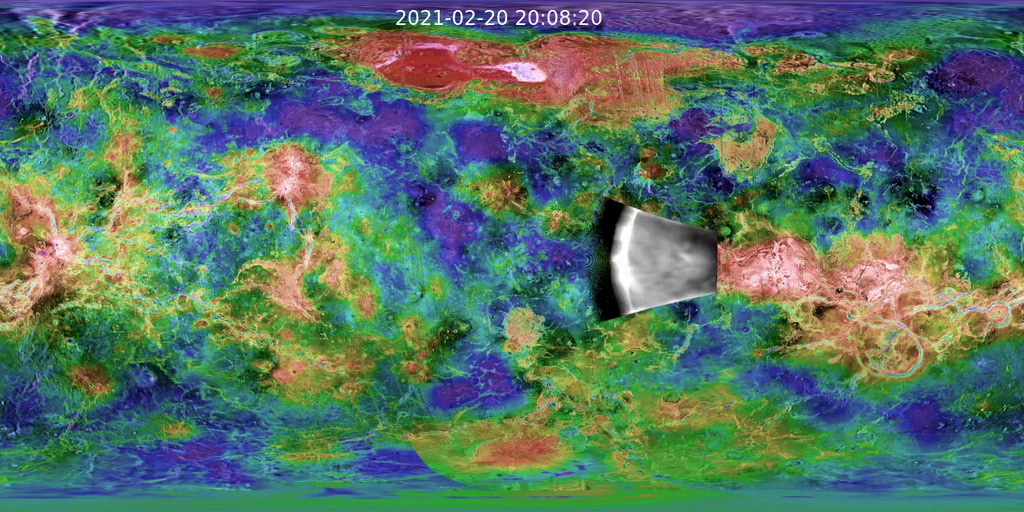

Next we visit Earth’s other planetary next-door neighbor. Holst casts Venus, the Roman goddess of love, as the “bringer of peace” in this soothing and beguiling movement.

Venus is about the same size as Earth, but closer to the sun. Fanciful depictions in the past of its surface portrayed a balmy paradise, and Venus is indeed our warmest planet.

But under a planet-wide shroud of highly reflective clouds is a climate that has evolved very differently than Earth’s.

Beneath high altitude electrified wind and 15 miles of sulfuric acid clouds, the unbreathable carbon dioxide air is a “greenhouse gone wild,” with surface temperatures hot enough to melt lead and crushing atmospheric pressure 100 times greater than what we feel on Earth.

Although not quite peaceful itself, Venus still has been a bringer of peace in at least one sense. Early satellite observations and study of the planet were among the first cooperative efforts of the Space Race between America and the Soviet Union.

Appropriately, Mercury is the “Winged Messenger.” The smallest planet in our solar system zips around the Sun closer than any other. Mercury completes a full circuit in its orbital relay race every 88 days, at varying speeds around 100,000 miles an hour.

At first glance, this tiny rock may look rather dull, but as we’ve learned, Mercury has a lot to say.

Despite how close it is to the Sun, there are places on Mercury that never see sunlight. We know now there is water ice hiding in these shadows.

One of Mercury’s more important messages to science was that this Albert Einstein guy might be worth listening to. Einstein’s theory of relativity explained a wobble in Mercury’s orbit that puzzled astronomers for 50 years.

Holst’s composition for Mercury features a fittingly brisk pace, with punctuated, almost Morse Code-like conversations among the instruments.

We move now from smallest to largest.

The gas giant Jupiter is our solar system’s most massive world (more than twice all the others put together).

Its Great Red Spot is a swirling maelstrom – bigger than Earth – that has raged on for at least 150 years, and perhaps much, much longer.

Jupiter is “the bringer of jollity” in Holst’s envisioning. This heavyweight world brings scientists so much joy in part because it has one of the best candidate spots in our solar system to search for life. The search for life elsewhere in the universe (life as we know it, anyway) is also the search for water.

Jupiter’s frozen moon Europa may contain a liquid ocean beneath its icy surface. Jupiter itself may not be so jolly a place to visit, but perhaps nearby teems a refuge of aquatic life?

The joy and excitement of new discovery is expertly captured in Holst’s tribute. If we do someday find life in Jupiter’s neighborhood, “The Bringer of Jollity” would make for an excellent discovery fanfare.

In ancient times, long before the advent of telescopes, Saturn was the most distant planet known. In the Roman pantheon, Saturn was a god of time, which connects well to Holst’s movement, “The Bringer of Old Age.”

In truth, Saturn is the same age as every other planet in our solar system, 4.5 billion years or so.

Its most striking feature by far is its ring system. From a distance they appear solid, but they are in reality a densely packed collection of tiny ice crystals and rocks.

Some of Saturn’s many moons happen to orbit through this debris disk and corral the mess, which is partly why the rings look striped.

Among Saturn’s 60 or so moons is a tiny, icy body called Enceladus, like a small version of Jupiter’s Europa.

And apart from this potential life-harboring spot, Saturn also fosters the only moon in our solar system with an atmosphere: Titan.

Larger than the planet Mercury, Titan is the only place in the solar system (other than Earth) with liquid oceans on its surface. But on Titan, they’re not of water, but methane and ethane.

Conditions for life to form on either moon may be harsh, but perhaps not impossible.

Holst’s Saturn is peaceful at times, and ominous, almost chaotic, at others. This diversity of sound is likewise reflected in the diversity of fascinating exploration possibilities Saturn offers.

Uranus is Holst’s magician. True to form, this hazy ice giant has more than one magic trick up its sleeves.

Uranus is so dim in Earth’s night sky that it hid more or less in plain sight for thousands of years. Not until 1781 did we identify it as a planet.

Even then, Uranus still had tricks to share. Rings were discovered by chance almost 200 years later. These tenuous “now you see them, now you don’t” bands are so faint as to be all but invisible to most telescopes.

The magic doesn’t end there: Every planet in the solar system more or less spins like a top in circling the sun – but Uranus rolls sideways, choosing instead to somersault.

Like any great magic act, Uranus is both bombastic and playful in Holst’s score.

The final planet in Holst’s suite and in our solar system is Neptune, where temperatures hit 350 degrees below zero [Fahrenheit] and icy winds blow at 900 miles an hour, more than five times the speed of a Category 5 hurricane. Its atmosphere swirls with intense storms, including Great Dark Spots, akin to Jupiter’s Great Red Spot.

“The Mystic” was mysterious indeed when Holst penned the piece. Neptune was only found in 1846, so in that sense, it is the “newest” of our solar system’s worlds.

Neptune is 30 times as far away from the sun as Earth. At that distance, it takes 165 years for Neptune to journey around our solar system’s central star. Neptune has just barely completed one full circuit since its discovery.

We began our journey this evening with “La Mer” and the waters of Earth. Now we conclude with Neptune, the Roman god of the sea. Holst wrote one of classical music’s first fadeaways to end his journey through the planets.

And how fitting an ending it is: As the sun’s influence fades beyond Neptune, to become just another star in the sky, we are left wondering what magnificence awaits us as we continue to reach out and explore the open seas of space beyond.

Credits

Please give credit for this item to:

NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center

-

Producers

- Swarupa Nune (InuTeq)

- Wade Sisler (NASA/GSFC)

-

Animator

- Brian Monroe (USRA)

-

Science writer

- Robert C. Garner (USRA)

-

Project support

- Michael Randazzo (Advocates in Manpower Management, Inc.)

- Kathryn Mersmann (USRA)

- LK Ward (USRA)

-

Editor

- Swarupa Nune (InuTeq)

-

Visualizers

- Scott Sheppard (GSFC Interns)

-

Greg Shirah

(NASA/GSFC)

Release date

This page was originally published on Monday, March 5, 2018.

This page was last updated on Wednesday, May 3, 2023 at 1:46 PM EDT.